This series of events organised by the Pavilion visual arts project based in Leeds was screening at the Hyde Park Picture House and a small venue in the Grand Theatre complex in New Briggate. At the invitation of the Pavilion Herb Shellenberger [from Philadelphia but now resident in London] curated an ambitious programme of films by artists; some film-makers but some artists first. Will Rose introducing the opening event admitted that the programme was larger than originally envisaged. There were seven separate screenings with 33 separate films ranging in length from 4 minutes to well over an hour. In his introduction Herb explained that artists based in Yorkshire were contributing but that their art works would be placed ‘in dialogue with work from international artists.

The opening event on a Friday evening saw the Picture House screening two 35mm prints: ‘Bliss it was in that [even] to be alive’. And better still the main feature was one of the outstanding masterworks from the French film-maker, photographer, writer, traveler and eccentric, Chris Marker. Marker died in 2012 after a life full of quirky artistic work. He was a collaborator with Alain Resnais and a friend and colleague of the recently deceased Agnes Varda. These two shared a love of cats. All three were part of the ‘left bank group’ ; a key but overlooked movement within the nouvelle vague. Their films were more experimental, more political and more distinctive than the famous ‘new wave’ films. Marker himself is known for works described as ‘essay films’ and this title is a good example of that approach. Not exactly documentary but addressing the actual world Wikipedia defines [informal] written essays as characterised by:

“the personal element (self-revelation, individual tastes and experiences, confidential manner), humour, graceful style, rambling structure, unconventionality or novelty of theme,”

Much of this will be found in the Marker film. As well as his personal involvement in so much of the production of the film Marker also appears in slightly fictionalised versions of himself.

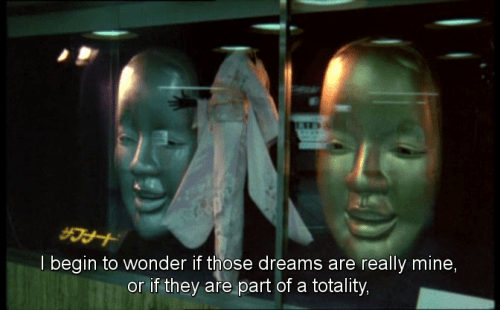

The film’s written component is a series of letters read [in parts] with comments by an unidentified female character. The letters are from a cameraman visiting a variety of places: Japan, Guinea-Bissau, Cape Verde, Iceland, Paris, and San Francisco. The last includes locations used in Alfred Hitchcock’s highly regarded Vertigo (1958), a film that has pre-occupied Marker for years. He remarks that he has seen the film nineteen times; I am not sure if I have ever seen a film that many times, but it could be Battleship Potemkin / Bronenosets Potyomkin (1925 USSR). I actually did the same homage to the Vertigo with a French guide and Marker fan.

The largest part of Sans Soleil are the sequences from Japan and from Guinea-Bissau / Cape Verde; societies that Marker suggests are

“two extreme poles of survival.”

This is illustrated in the film. Marker also notes the political context with archive footage of the African Liberation struggle and one charismatic leader, Amilcar Cabral.

The original French version of Sans Soleil opens with the following quotation by Jean Racine

“L’éloignement des pays répare en quelque sorte la trop grande proximité des temps.”

(The distance between the countries compensates somewhat for the excessive closeness of the time).

Marker shot the film on a 16mm camera in colour and standard European widescreen. There is found footage and stills/freeze frame in colour and black and white academy. And some of the film is synthesised by a colleague. He recorded the soundtrack in asynchronous manner, thus the sound does not always match the imagery. So this is ‘montage’ in the full sense of the word. The screening presented the original French language version in a 35mm print in good condition.

Sans Soleil was preceded by a short five minute film, also on 35mm. This was Black by Anouk De Clercq (Belgium, 2015). This was the only print of this art work which by now was showing signs of wear and tear. The sub-titles noted this suggesting the film picked up on a point early in the Marker film where the film-maker addresses the use of black leader. I did wonder if either film-maker had the Soviet artist Kazemir Valedich in mind.

The second screening I attended was titled ‘The Gentle Touch’ and presented five titles featuring:

“Stone, flesh, blood or electric circuit, feet on the ground versus data in the cloud. From automaton to avatar, artists reflect on the tension between our own individual, physical bodies and the animated, virtual body.” (Curator’s Notes)

Three of the regional film-makers attended and spoke about their work after the screening.

The first title was The Love of Statues (2019) by Peter Samson, based in Doncaster. This was a combination of film, found footage and archive stills. Shot partly in Paris at the museum of the Salpetriere Asylum containing a bevy of C19th objects. It was shot in black and white and partly in widescreen and partly in academy ratio. Peter explained that he had worked on the material several time over the years and this was the most recent version. He had to edit together materials in different ratios. The theme at the asylum was hypnosis and hysteria but the visual theme of this title was bodies in relation to both statues and automaton. It had an eerie feeling and much of the film was in chiaroscuro.

Self-digitalisation (2015) by James Thompson ran for nine minutes in colour and widescreen. This was in a single long shot of a picture gallery at Hospitalfield House where Thomson was on an artist residency. The film aimed to ‘re-interpret’ the room and objects as a young man took a series of digital self-portraits, ‘selfies’. These were done at speed in an arch manner. If we were meant to look at the art through these it failed for me; and as a satirical take on the ‘selfie’ it needed more angles or positions.

Dog’s Dialogue / Colloque de chiens (France 1977) was a 22 minute ‘photo-roman’ by Raúl Ruiz, screened from a colour 35mm print. The English sub-titles were projected digitally. A ‘photo-roman’ uses a series of still shots to offer some sort of narrative. This one was unconventional as it included moving images, both of the titular dogs and, later, of a location. The various dogs, mainly tied up and barking, were some sort of metaphor. The humans in the story proper went through a cycle of events that

“consists of news items collected in magazines. A melodramatic pseudo-detective thread woven round imagery from women’s magazines.” (Institut Français).

In what seemed to be a homage to the photo-roman’s founder, Chris Marker, at one point a ‘still image’ turned into a brief moment of movement.

This film was typical of Ruiz’s work in France, where he was an exile after the coup in his native Chile. His work was literary, ironic, sardonic and experimental. It was also, as with this title, always engaging.

Another film on 35mm with digital subtitles was Au Père Lachaise (France 1986) a thirteen minute title by Jean-Daniel & Pierre-Marie Goulet. This is a Municipal cemetery in Paris, apparently the most visited in the world It is the earlier example of as ‘garden cemetery’. Many famous people lie there, notably Oscar Wilde. And the Institut Français offered a quotation from another famous inmate, Honoré de Balzac.

“It’s all of Paris but seen through the looking glass, a microscopic Paris reduced to the dimensions of shadows, larvae, death, a human race that has nothing more than vanity’”

The vanity is obvious in some of the monumental graves, similar to those found in London’s Highgate cemetery. However, the film was more interested in the space, arrangement and foliage; something that disappointed at least one viewer.

The film used a series of tracking shots, interspersed with long shots to close-ups; reminiscent of the style of Alain Resnais. To its credit the film did end with an note about 147 people associated with the cemetery; the heroes and heroine so f the Paris Commune, executed nearby and commentated by a simple plaque.

The Turning of the Helmet (2018) by Rhian Cooke, an artist currently involved in the Yorkshire Sculpture International. The film ran 3 minutes in colour and 16:9, [television funding]. The opening of the film used animation techniques playing with ceramics and textiles to offer a sense of the helmet. The later stage expanded into actual cinematography to present a pill box which was an inspiration for work with a helmet. This was well done but [for me as is often the way with very personal experimental film] I did not really engage with the thematics.

I had a similar problem with Soft Body Goal (Finland, 2010) a four minute title by Jaako Pallsasvuo. This combined digital animation and dubbed sound with a bevy of bodies;

“Body without bone. Sloppy and improper. Body seepage. Naked sewer rats. Hairless aristocratic cats. Slime …. the body of the future ….”

However, the techniques used were impressive.

We almost did not see the final title, Ice Cream. This was a 1970 16mm film copied onto a digital format; I suspect there were compatibility problems because we had three false starts. However, the film repaid the wait. The director, Antoni Padrós, was an underground Catalan film-maker. Born during the Spanish Civil War most of his career was spent under the Francoist dictatorship. His film work was subversive, iconic and iconoclastic. This title featured two young people, explicit sex and the titular ice cream. It clearly subverted and made fun of the repressive values and censorship of the times. One could almost imagine a Franco stooge banning ice creams for a period.

I felt that the older European titles had political as well as aesthetic stances. Whereas the more recent British titles were far more personal and did not have overt political themes: They were also apparently more preoccupied with aesthetics. The former are closer to the key film of the programme, Sans Soleil, which combined politics and aesthetic in a complexly cinematic manner.

A third programme was ‘Sail the Summer Winds’. I was unclear regarding the overall programme title: sea-scapes seen a common feature.

The opening film was A Mysterious Devotion (1973), written and directed by Alf Bowers & Andy Birtles. They were fellow students at what was then Sheffield Polytechnic. This institution funded the filming. The completion and editing was done by Bowers whilst a student at the new National Film School.

Herb Shellenberger in his written introduction commented;

“Alf Bowers A Mysterious Devotion evidences several decades of wildly creative and experimental film-making in Yorkshire. The ambitious 16mm cinemascope film [in black and white] is an oblique narrative following several members of a family as they experience and process a traumatic death. There is no dialogue but the camera stalks its actors around the house and at the seaside, at times claustrophobically close and others in wide shots at the sea.”

Alf Bowers and answered questions after the screening. He noted that the film was based on ideas that were in

“the heads of the protagonists … things that could have happened.”

He suggested the only event that was certainly actual was the death of the father at the opening of the film. And the plotting followed the proposal by Jean-Luc Godard,

“A story should have a beginning, a middle and an end, but not necessarily in that order.”

The film was shot in a house in Sheffield and at Flamborough Head. The anamorphic lens used was a projection model, which made the camerawork extremely difficult, The film used filters for one shot and high speed cinematography for two sequence. The film stock used was Kodak Plus-X, [also used on Schindler’s List ( 1993). This produced a high-contrast image. However, whilst there is a 16mm print available the film was screened from a digital copy. There was apparently a technical reason for this. However, the digital copy did not really do justice to the high-contrast imagery: most of the film was reasonable but there were two sequences, including the end credits, where the images was not distinct enough. This was the first screening of the film for about 20 years so it is a shame we did not see a pristine version . It remains a powerful and impressive short film, running 47 minutes.

The Eraser / Keshigomu (Japan, 1977) by Shūji Terayama. This was a 20 minute film on 16mm in colour and academy. The setting is a seashore and we see several characters posing here and in an interior. But the image is overlaid by video filter patterns. And a hand appears frequently using the technique to erase part of the image. As Herb Shellenberger commented,

“a unique conceptual work that is difficult to define.”

Alaska (Germany 1969) by film-maker Dore O who co-founded the Hamburger Filmmacher Cooperative. In black and white and colour the film shared a technique with The Eraser: in this example polka dots cover and obscure a range of subjects, animals, people, settings. The film also has a distinctive sound track using musical instruments, machine noise and recorded sound. Herb Shellenberger’s comment is similar though:

“a film that resists all interpretations.”

All three films demonstrated film-makers working with unconventional and experimental techniques.

I was able to catch three of the seven programmes so my sense of the overall was limited. However, this was an impressive collection of artistic films, many of them rare, especially in theatrical presentations. It is good that The Pavilion and the Hyde Park Picture House were prepared to be so adventurous. The largest audience was for Sans Soleil, the best known work in the weekend. Other audiences were smaller but we are dealing with avant-garde work. It is nice to know that an audience exists for this less commercial but influential area of cinema.