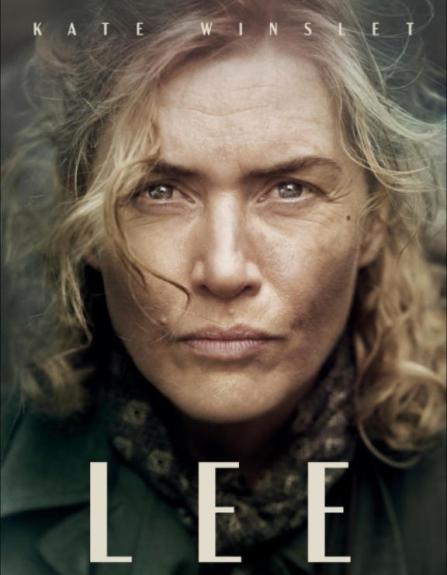

Shown at Toronto in 2023 but not released in the UK or US until this month, Lee is a handsome and well-made film that tells the story of a major figure of the 1930s and 1940s, the photographer Lee Miller. It’s a slightly fictionalised story, a partial biopic supported by the estate of the American woman who became a model and then a celebrated photographer. There have been several attempts to tell Miller’s story previously but all failed to take off until this project which began with the partnership of Kate Winslet and Ellen Kuras established around seven years ago. Winslet felt this was a woman’s story that needed to be told by women. She herself would be a co-producer as well as playing the lead and Kuras, a celebrated cinematographer, would direct this as her first cinema fiction feature (she has directed TV films and series and documentaries).

Lee Miller (1907-1977) was born in Poughkeepsie, NY and became a fashion model in the 1920s. Moving to Paris she developed her skills as both a fashion and fine art photographer. At this point she was part of a crowd of surrealists, living with Man Ray and friends with John Cocteau. During the mid-1930s she was married to an Egyptian and took photographs in less formal conditions in Syria and elsewhere on her travels but eventually returned to Paris and became involved with the British surrealist Roland Penrose. She accompanied him to London in 1939 and got work as a photographer for Vogue in London. Eventually she became frustrated about not being at the centre of the ‘action’ and pushed hard to get accepted as a war correspondent and photojournalist. Finally accredited by the Americans, she followed the US Armed forces on their advance across Europe from 1944. After the war she returned to England and her son Antony was born in 1947. She continued to work occasionally as a photographer but also became known as a gourmet cook. The Penrose home in East Sussex attracted the artists she knew. Antony Penrose became the keeper of his mother’s archive of 60,000 images after her death and it is one of his books that is the source for the script of the film. The film narrative by necessity focuses on the years from 1938 to 1945 and in doing so some details and dates are changed. Liz Hannah, John Collee and Marion Hume wrote the script and Lem Dobbs worked on the original story idea.

The film has a classy cast with Winslet attracting friends from previous shoots such as Marion Cotillard as Solange, the editor of French Vogue and younger rising stars such as Josh O’Connor who in effect becomes the external narrator of the story questioning Winslet as Lee Miller in her seventies. Noémie Verlant plays Nusch Eluard, the other of Miller’s close women friends in Paris. Andrea Riseborough is terrific as Audrey Withers the editor of British Vogue. The only casting decision I’m not sure about is that of Alexander Skarsgård as Roland Penrose. I knew that I recognised him but he didn’t seem to ‘fit’ as well as the others. I think that Jude Law was the original choice and that would make more sense. Both Winslet and Skarsgård are older than the real Miller and Penrose would have been but more importantly Penrose was older than Miller whereas the actors are roughly the same age. The final important figure to mention is the Life photographer David Scherwin who became Miller’s companion and helpmate as a war correspondent. Scherwin was younger than Miller and he was Jewish so very much affected by the scenes at Buchenwald and Dachau that the pair visited and photographed. He’s played very well by Andy Samberg. Miller herself was deeply wounded by what she forced herself to photograph.

I think that the film may throw up different challenges and responses across segments of the audience. I’m familiar with all the historical events which Miller photographed and I’ve seen some of the images she produced before but although I know something about the Surrealists and the other various characters, I didn’t necessarily recognise them all. Will younger audiences get all the details from the dialogue? I think there were some intertitles giving dates and locations but the narrative might be hard to follow in detail. The most important narrative theme is that Miller was able to provide a woman’s view of what was happening almost on the frontline. She was also highly skilled and adept at handling her Rolleiflex camera in many tight situations producing images that were punchy in their content and also examples of great photojournalism so that they communicated very effectively – too well perhaps in the case of the images from the death camps which were held back in the UK and only published in America. The Rolleiflex was a large format camera producing excellent results but more difficult to use than the smaller format cameras such as the Leica – both German products. Miller discovered that she could not get access to the frontline of the British Armed Forces and so fell back on her American passport and was allowed, albeit reluctantly, into forward positions. There is an interesting section in which Miller on a visit to an RAF station is kept out of the main hangar and finds a hut proclaiming ‘No Men Allowed’. She meets a WAAF (Women’s Auxiliary Air Force) flyer who is one of the many women working for the Air Transport Auxiliary as ferry pilots. These women could fly most different aircraft types from the factory to the operational bases. Photographing the many women at work during the war was an important propaganda exercise but Miller wanted to be where the ‘action’ was. I think it is a little strange that despite being based in the UK from the start of the war and returning to live in London and in East Sussex up to her death in 1977, she doesn’t seem to become part of British society in this film. But it is only a partial biopic. The photos she takes of women in France and Germany after D-Day and up to VE Day are the most important focus.

If you want to know more about Lee Miller, there are various websites, including the Lee Miller Archives overseen by Antony Penrose, which includes thousands of images in its ‘Picture Library’. Kate Winslet and Ellen Kuras have given interviews such as this one reported in the Guardian in which they explains the struggle to get this film made. I think there is a general agreement among most reviewers and commentators about the success of the project to get this woman’s story on screen. The current debate about the film seems to boil down to the trade-off between showing what Miller achieved against the ‘conventional’ mode of the storytelling and presentation. I’m not sure this is helpful. Sight and Sound‘s reviewer Sophia Satchell-Baeza in the current October 24 issue is perhaps typical in arguing that the film offers that “to ignore the messiness of her [Miller’s] romantic life completely is to offer up a flat and two-dimensional portrait . . .” It’s true that a far more complex narrative could have been constructed from the material available but that would have produced a longer and more expensive film and might not have appeared at all. I did ask myself if the material would have worked better as a TV mini-series but I don’t think that could have the impact of a more condensed cinema feature and if Kate Winslet’s film gets the Oscar nominations it deserves the impact could be considerable. As it is the film is a UK majority production from Sky running at 116 minutes with a 1.85:1 image. Ellen Kuras has some Polish heritage in her family background and she has chosen Pawel Edelman as her cinematographer. He has worked on the later films of both Andrzej Wajda (e.g. Katyn, Poland 2007) and Roman Polanski (The Pianist, France-Ger-Poland-UK 2002) depicting massacres and the Holocaust. The shoot ranged across Croatia and Hungary with some work in the UK. Visually there is a sharp contrast between the bright colours of France in the opening and the muted shades of the frontline in 1944-5. I would argue that the balance of the visual narrative and the dialogue succeeds in telling a complex story, though perhaps Alexandre Desplat’s score is a little disappointing on a first hearing – I can’t recall noticing it. In conventional terms that’s a win, I guess. I found the film riveting and moving and I recommend it highly but also urge you to seek out the Lee Miller archive and take the time to look at the remarkable images produced by a remarkable woman. I hope very much that the film finds its audiences. Can I also recommend looking out for the earlier film Mr Jones (Poland-Ukraine-UK 2019) by Agniezska Holland, a similar kind of film about an individual trying to tell a story about the horrors of the mid 20th century.

Lee is in UK cinemas now and opens outside the UK next week. Mr Jones is on BBCiPlayer for the next few months.

The movie is very well made and Winslet is excellent, supported by a strong cast. I was distracted by the scripting. There is a scene with surrealist friends which is somewhat misleading; and, like other scenes, too ambiguous. And I thought the structure tried to be a little too clever. Definitely worth seeing.

LikeLike

You have persuaded me to see this. Normally I am not keen on bio-pics (I know the story) or biopic acting which seems to be showing off about skills in presenting a character (and often wins Oscars). But it’s on down the road so I’ll go this pm,

LikeLike

I hope you enjoy it!

LikeLike

only recently caught this and had quite forgotten that you had reviewed it. I think I was seduced into watching by names in the cast like Noemie Merlant and Marion Cotillard, both usually wonderful but both entirely wasted here and completely ancillary to Lee Miller who dominates the action. The problem I had with this is the problem I thought I was going to have, which is that the Holocaust is a big subject and one should tread carefully in constructing a film around it that is basically the story of its impact on some well-meaning adventurer dragged into its orbit. Films like ‘Son of Saul’, for instance, offer us no heroes but leave a bigger impression.

LikeLike

I think we’ll have to disagree on this one. I don’t think the film is ‘about’ the Holocaust as such. It’s about Lee Miller, a celebrated photographer accustomed to fashion and art photography who became a war photographer. She didn’t know she would be photographing the horrors of Buchenwald. She was not an ‘adventurer’ as I would understand the term. She wanted to show that women could do a certain kind of wartime job.

LikeLike

I have a drawning about Lee Miller in 1925, made by her hungarian teacher Ladislas Medgyes in L’École Medgyes pour la technique du théatre.

If somebody is interested in write me to Hungary : budabest.kft@gmail.com

Best, Jan

LikeLike

I Think Kate Winslet would be a great choice as Slim Keith in Limited Series about Slim Keith

LikeLike

I think this may refer to the second series of Feud which deals with Truman Capote and a group of prominent society women in the 1950s known as The Swans. The group included the first wife of Howard Hawks, ‘Slim’ Keith, portrayed in the series by Diane Lane.

LikeLike

I Think Marion Cotillard would be great choice as Sage In MCU

LikeLike

I Think Kate Winslet Is the G.O.A.T.

LikeLike

I Think Marion Cotillard Is the G.O.A.T.

LikeLike

I’m not sure this comment adds much to the discussion of the film. Perhaps this is some form of AI scam? Any future comments of this kind will be deleted but discussion of the film itself is welcomed.

LikeLike