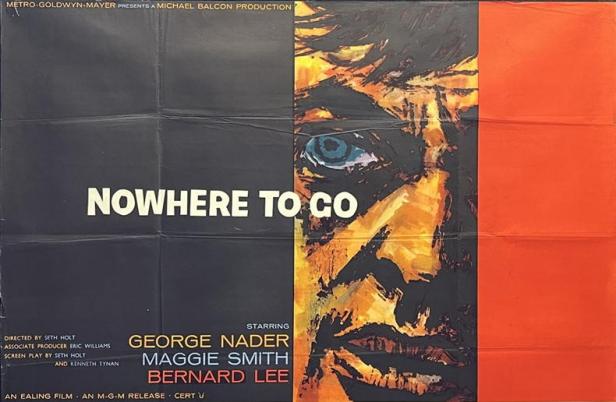

The penultimate film from the period of ‘Ealing Films’ production, Nowhere to Go is an unusual film for both Ealing and British cinema generally in the 1950s as well as being the first feature directed by one of the most singular Ealing figures, Seth Holt. There is a great deal to say about the film, Ealing and Seth Holt, but I’ll try to keep this posting as concise as possible and perhaps write about all three in more detail at a later date. In December 1957 Ealing Studios, under the overall control of Michael Balcon since 1938, started production on its last film under a six-picture deal with MGM-British at Borehamwood. There would be just one more Ealing production after it, in Australia, The Siege of Pinchgut, released in 1959, the last of 95 pictures made by Michael Balcon under the Ealing Studios banner.

Seth Holt joined Ealing around the age of 20 in 1943 as an assistant editor, helped by a word from his brother-in-law Robert Hamer who would later be hailed as perhaps the great auteur director within the studio production system established at Ealing. Holt graduated to editor by 1949 and then producer by 1954. The script for Nowhere to Go was written by Holt and the theatre critic Kenneth Tynan, who was briefly contracted at Ealing. Tynan was an unusual choice for Ealing. He was Oxford-educated and most of Ealing’s creative figures were also university graduates but Tynan stood out because he was both socially radical and dismissive of the staid plays of much of British theatre. Ealing was generally seen as producing small scale ‘quality’ pictures presenting a rather middle-of-the-road sense of British life. As well as his Ealing role and his print journalism Tynan became involved in writing for radio. Seth Holt was unusual in not having gone to university, instead spending a term at RADA and then working in rep theatre as an actor. The pair could be expected to produce a different kind of script. They adapted a novel by Donald MacKenzie (1918-93), Canadian-born but well travelled. MacKenzie was arrested in different countries and used his experience of short prison spells in his crime novels which had an authenticity of language across many titles. Nowhere to Go was published in 1956.

Because of the MGM link, the film was more likely to get exposure in the US and it has gained a reputation through screenings on TCM where it has been hailed as a good example of a British film noir. But unfortunately this also leads to some misunderstandings about Ealing as a studio. The film’s casting utilises an American actor to play the lead, a Canadian conman in London. George Nader was a contract-player at Universal and an actor in US TV in the early 1950s. It was common for Hollywood actors to appear in European films in the 1950s and 1960s, both stars in big ‘international’ productions and more modest players in European domestic films. Ealing hadn’t done it much before with only the Canadian Robert Beatty appearing several times in small roles and leading in Another Shore (1948) and Paul Douglas playing an American in The Maggie (1954) standing out. Douglas was a genuine Hollywood figure in 1954 and there are two opposing theories as to why casting Americans in British pictures was considered a positive move. One argued that a Hollywood name in the cast was more appealing to working-class British audiences who generally preferred American films. The other argued that with an American in the cast, any film stood more of a chance of a North-American release. Both might well be true in some cases. The last Ealing film, The Siege of Pinchgut in 1959 featured the rather better-known Hollywood figure of Aldo Ray.

Nader was cast as Paul Gregory a Canadian who fought in the Second World War and stayed on in the UK. He has become adept as a con-man and the central idea of the narrative is that he has met a wealthy Canadian widow – played by Bessie Love from Texas who had been a significant Hollywood star from the 1910s to the early 1930s when she came to work in the UK. She is attempting to sell a valuable coin collection that belonged to her husband. Gregory begins his con, perhaps appropriately, at an ice hockey game at Wembley Arena. Ice hockey was a popular sport in the UK in the late 1940s and throughout the 1950s. He must persuade her to let him sell the coins for her. He’ll then have a chance to get access to the £55,000 that the sale should bring. But in an audacious bit of narrative re-structuring, Holt starts the film with a virtually wordless sequence in which Gregory is ‘sprung’ from his prison cell by his partner in crime, Victor Sloane also a war veteran, played by the usually upright Bernard Lee. Being arrested was part of Gregory’s plan following his theft and sale of the coins but he did not expect such a long sentence. Once out of prison, a long flashback shows how he had conned the widow and brings us up to date. The classic enigma is whether Gregory can recover the money he stole, from its hiding place before the police re-capture him. But will Sloane accept the measly sum Gregory is paying him? What if he wants a bigger share?

One of the criticisms of the film is the title as it does seem to suggest that there is no way out for Gregory. As he is the protagonist, do we expect him to ‘win’ in some way. Is he the one who has ‘Nowhere to Go’? It sounds like the film will have a ‘down’ ending, which might work better for an arthouse picture rather than a mainstream ‘entertainment’. Crime films in the studio system used to end with confirmation that ‘crime does not pay’ – but had audiences gone beyond that by 1958? The other way to think about this is to argue that this is more of a ‘howdunnit?’ – the interest is more in how Gregory plans and carries out his crime and then how he attempts to recover the loot and escape. In this respect the film has quite a lot going for it. First, the script draws on Donald MacKenzie’s knowledge of the criminal underworld in London. This includes the language they use, the code of support and the costs etc. In this sense Gregory’s actions and what happens to him are very interesting. We meet a range of British character actors including Harry H. Corbert as a gang boss, Lionel Jeffries as a pet-shop owner and Howard Marion Ceawford as a club owner. But the most interest by reviewers tends to be in the appearance of Maggie Smith in one of her first film roles. One suggestion is that Kenneth Tynan, who was aware of her stage performances, recommended her. She was 23 when she took the role having appeared uncredited in an earlier film and in several TV shows. She plays a middle-class young woman, Bridget Howard, who claims to have been expelled from several, presumably private, schools and meets Gregory in the apartment Sloane has found for him. The apartment owner is mysteriously absent with suggestions that he might be keeping away from the police or perhaps from Smith’s character? She will meet Gregory again later and become more involved. Strangely, one American reviewer refers to her character as ‘working class’ (!) and a British reviewer refers to her as an ‘ex-deb’. Some of these confusions might be explained by the cuts made to the film by MGM in the UK and US. IMDb lists the film at 89 minutes. Monthly Film Bulletin (January 1959) lists 87 minutes. Charles Barr in Ealing Studios (1977) gives the length as 97 minutes. I’m not sure of the length of the print shown on Talking Pictures TV but Seth Holt himself argued that MGM cut 15 minutes, intending the film as the bottom half of a double bill in the UK.

Another well-known character actor is Geoffrey Keen as the police Inspector hunting for Gregory. The Inspector is always in the background in the second half of the film, just one step behind Gregory. This does make me think of the French polars in which there is sometimes a more direct interplay between the police and the criminals, e.g. in Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le cercle rouge (France-Italy 1970). Monthly Film Bulletin‘s reviewer suggested that in Nowhere to Go the approach was “too derivative of the current French and American crime schools styles with their jazzy soundtracks”. Later, however, this would become one of the features that excited cinephiles. Holt’s prison break sequence comes before the classic break-out in Jacques Becker’s Le Trou (France 1960). Nowhere to Go has a music score by the Jamaican jazz group leader Dizzy Reece and it is indeed one of the strengths of the film. The other aesthetic triumph of the film is the mise en scène and the cinematography of Paul Beeson who, like Bernard Lee, was involved with Dunkirk (1958) at Ealing the year before (and The Shiralee in 1957). The photography is striking in the prison break-out sequence (filmed near the old Kew Bridge Station in Brentford). Several scenes feature carefully constructed deep focus shots in interiors and two specially constructed apartments for difficult meetings between Gregory and Sloane. It is the camerawork that arguably moves some reviewers and scholars to term this a ‘British noir‘. I’m a little wary of that label but 1958 is close to the end of the classic Hollywood noir period. The photography is very fine and reminds me of the late 1940s/early 1950s of Ealing such as Cage of Gold (1950) a noir melodrama and a non-Ealing film like The Long Memory (1953) by Robert Hamer. The representation of London streetscapes is excellent, covering Covent Garden, Oxford Street and the mews further west. It contrasts well with the wintry fields representing the area around Brecon at the end of the film.

Nowhere to Go is presented in ‘Metroscope’ which was not an anamorphic process but a hard-matted spherical process that could be projected at any ratio between 1.66:1 up to 2.00:1. Some sources suggest that MGM intended it to aid cinemas not yet fitted with ‘Scope screens. In this case projection prints were intended for 1.75:1. This is virtually identical to the 1.78:1 aspect ratio of contemporary 16:9 widescreen TVs. I have now watched the Studio Canal DVD from 2013 which seems to be 1.78:1 and runs 103 minutes (the figure listed in the BBFC records for 1958). The film really should be available on Blu-ray. I think it’s a real gem. Apart from the 2013 DVD and its Talking Pictures (UK) and TCM (US) screenings, it doesn’t seem to be available on streamers. It has to be seen if you are interested in Ealing since Holt set out to make the most ‘non-Ealing film’ he could and he succeeded.

Well I’ve never heard of this film but it looks great! Thanks for the review!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hope you can get to see it.

LikeLike