David Bordwell, who died recently after a long career researching, teaching and writing about film, became a faculty member at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 1973, retiring in 2004 but keeping working as Professor Emeritus. I don’t remember when I first became aware of his writing (with Kristin Thompson) but it was probably around the early 1980s. My copy of Film Art is a second edition from 1985, the first edition appeared in 1979. The current edition is the 12th published in 2019. Bordwell collaborated with several other scholars. He and Kristin were joined by Janet Staiger for The Classical Hollywood Cinema first published in 1985 and a mainstay on style and production in the Hollywood studio system ever since. Film Art alone would make Bordwell a major figure in film studies but there are least five more titles on my bookshelf and more in pdf files on my desktop. It’s a staggering achievement to have written so much accessible material and to have inspired so many readers.

I never met David Bordwell or saw him in person at events, I only know about him through his writings. Back in the 1970s there were North Americans who attended the British Film Institute Summer Schools and there were UK film teachers and scholars who did visit the US, but these were relatively rare moments of exchange. Bordwell stood out as not only a teacher and writer, but also as a researcher. This meant he did travel to visit overseas festivals and archives and the results appeared in books like Film History (which was an essential resource written with Kristin Thompson from 1994 onwards), Planet Hong Kong in 2000 and books on directors such as Ozu, Dreyer and Eisenstein. His work also embraced contemporary American cinema but it situated all cinema in the context of films made in different national industries and over the whole period of filmmaking. That’s partly why his work and that of Kristin Thompson has been important to me. As well as his many books and published papers the David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson blog, ‘Observations on Film Art‘ as part of ‘David Bordwell’s website on cinema’ has provided a form of running commentary on screen studies as it has developed.

You might ask why Bordwell did not engage so much with film studies as it developed in the UK, France and among his contemporaries in other US universities. The answer lies in his main focus on film form and film styles. Here’s a quote from Bordwell’s blurb about his 2007 book Poetics of Cinema:

Today there are many scholars studying the film industry and probably many more seeking to understand filmic reception by studying audiences in their sociocultural contexts. For those researchers, all the films on earth could dissolve into nothingness tonight, and they’d get up next morning and keep going without losing a beat. Film history without films doesn’t work for me. I need my movies!

Bordwell has sometimes seemed hesitant about his own status as a film theorist. His work has been most concerned with the formal properties of film narrative: how films produce meaning through narrative and visual and aural styles and how spectators engage with the viewing process. His most ‘theoretical’ book was Narration in the Fiction Film, first published in 1985. In this book he begins with the Poetics of Aristotle and develops his ideas around the work of the Russian formalists of the early 20th century. Bordwell came from a literature background and I note that the blurb for his Narration book places him as a ‘Professor of Communication Arts’. I’m not sure about North American universities but in the UK in the early 1980s, it was still rare to find academics who held posts in ‘Film Studies’ rather than ‘Communications’ or something similar. Many of those early into the new field came from a literature background and in the UK in particular that meant a need to ‘break away’ from the traditions of English literature. The import of theoretical ideas from other disciplines such as linguistics was part of that process. Bordwell was aware of what was happening in the early 1970s but he was dissatisfied with it for various reasons and he developed a position from which he could study narrative and narration and how film readers engaged with films through a ‘perceptual-cognitive’ process. Personally I found Bordwell’s writing helpful in thinking about how to teach about films for several reasons.

He often started his books with an entertaining story or a joke. Here’s how he opens the third chapter of Poetics of Cinema (which is available as a pdf on the Bordwell website/blog):

A man sitting in a bar suddenly shouted, “All lawyers are assholes!”

The customer next to him jumped off his stool. “Those are fighting words!”

“Oh, so you’re a lawyer?”

“No, I’m an asshole.”

He points out that this joke is different from other forms of humour. It requires the reader to have some understanding of the culture of bars and the status of lawyers in American society. As he puts it: “Our narrative competence relies on social intelligence”. I’ve always enjoyed teaching narrative and narration and I’ve found starting with a joke can work well.

Another strength of Bordwell’s approach is that it has an empirical dimension and it links theory to practical criticism. In other words, theoretical work on films requires discussion of films in detail. This sounds pretty obvious but I can remember several film theorists who rarely went to the cinema and limited their study texts to a few titles. Bordwell had an encyclopaedic knowledge of American films as well as many films from a wide range of other cinemas. He was also well-clued in to whatever was happening in cinemas at any time. I remember when I thought I was fairly up-to-date writing about Slumdog Millionaire in 2009, only to discover that Bordwell had already made the same points in greater detail on his blog.

A third strength of Bordwell’s published work in particular is his use of ‘frame enlargements’, what we would now see as ‘screengrabs’. I think there is a difference in US and UK copyright and permissions/reproduction fees. Anyone who has written about film in the UK knows both how difficult it has been to get permission to use stills from Hollywood studio shoots and how much the studios demanded as a fee. Often it has been just too expensive to allow more than a few isolated images in a publication. By contrast, the 1994 Film History book by Thompson and Bordwell is filled with images, including several pages of beautifully-reproduced colour images. It makes a big difference.

David Bordwell’s career as a teacher and writer spanned close on fifty years and in that time ideas about film theory and film studies changed significantly. In 1996 Bordwell, together with the philosopher Noël Carroll, edited a collection of papers under the title of Post-Theory: Reconstructing Film Studies. As the editors’ Introduction sets out, this is not a book about the end of film theory, but instead a response to the idea of a ‘Grand Theory’ of film, the collection of theoretical work drawing on “Lacanian psychoanalysis, Structuralist semiotics, Post-Structuralist Literary Theory and variants of Althusserian Marxism”. This was what became the dominating framework of film theory in Anglophone film studies, sometimes referred to in the UK as ’70s theory’ or ‘Screen theory’ (referring to the academic journal Screen). Bordwell saw himself as not necessarily rejecting the ideas expressed, so much as the monolithic nature of a ‘Grand Theory’. The edited collection in a sense proposes “a middle-range enquiry that moves easily from bodies of evidence to more general arguments and implications”. I should also point out that in 2000 Christine Gledhill and Linda Williams edited another collection of essays under the title Reinventing Film Studies which also engaged with the fall of ‘Grand Theory’ and in doing so took up discussion about the concept of ‘middle-range enquiries’. The development of social media over the last twenty years has arguably shifted the focus again and I do fear that some of the important arguments explored in these two collections are in danger of being lost. This is not to argue against the identity politics of Queer Cinema, Black Lives Matter or #MeToo but to suggest that they still need to be rooted for film students in arguments about the films themselves, how they are produced and how they are read.

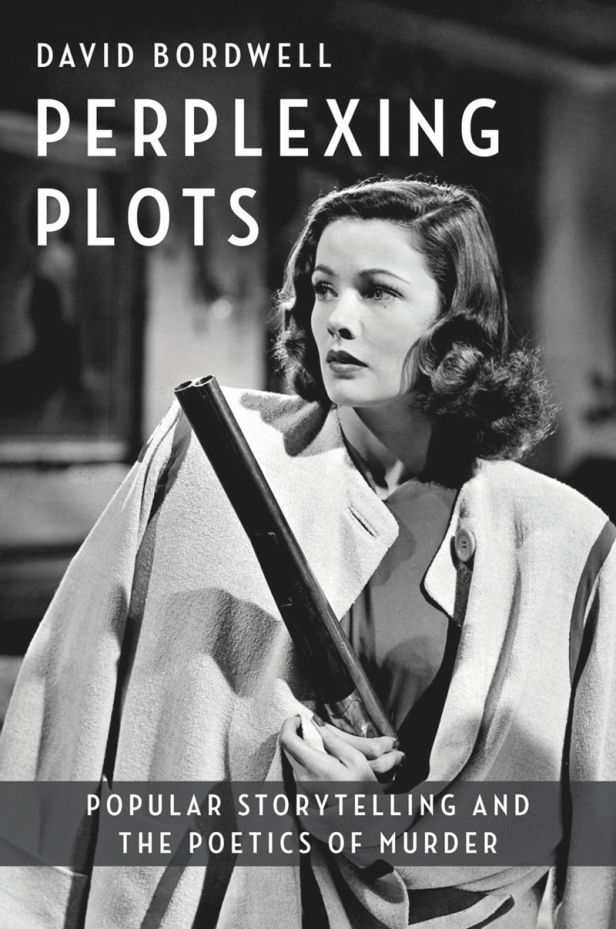

I confess that during the last few years I haven’t read too much by Bordwell but when I was still working with students on contemporary American cinema I did make use of his 2006 book The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies. I found it very useful. Before writing this blog piece I read through several entries on the Bordwell blog and I realise that I share with him a fascination with crime fiction. I’m wondering whether I should now purchase his last book, Perplexing Plots: Popular Storytelling and the Poetics of Murder (2023).

I’m sure I will be dipping into all the books and other writings over the next few years. David Bordwell leaves a great legacy embodied in his writings. They are particularly important because his readers are not only film studies students, but film historians, archivists, filmmakers and film critics and simply anyone interested in the ‘serious fun’ of the movies.

I send my condolences and my best wishes to Kristin Thompson who must feel a tremendous loss in so many ways. She has written that the website will be maintained, so if you’ve never visited I urge you to do so and I’m sure you will find something to inspire you to watch more movies and think about them in different ways.

This is a good commentary on the work of a major contributor to film studies. I actually met David Bordwell a couple of times at Le Giornate del Cinema Muto. His filmgoing was as extensive as his writing. He also had a firm grasp of the operation of what we call Hollywood, the dominant capitalist oligopoly in the film industry.

An important contribution was his ‘Pandora’s Digital Box: Films, Films, and the Future of Movies’, David Bordwell, Irvington Way Institute Press, Madison, Wisconsin 2012. It seems to have only be published electronically which likely accounts for it often being overlooked. The book studies the way that the digitisation process of international cinema was orchestrated to increase the control of the major film corporations. The book came out in 2012 and matters have developed since, but it is still a detailed and illuminating study of the process that dominates cinema today.

LikeLike

Yes, Bordwell (or perhaps Kristin Thompson) does mention on the blog about going to Le Giornate del Cinema Muto and meeting people. The Pandora’s Digital Box book is available on the website and I must add it to my collection. Thanks for the tip.

LikeLike