El diputado was one of the two films from the ‘Transition to Democracy’ phase of Spanish cinema in the 1970s that featured in HOME’s ¡Viva! Festival earlier this year and then re-appeared as part of the States of Danger and Deceit programme. I watched it at the Hyde Park Picture House as part of the Leeds Film Festival. Films like this are interesting for several reasons – not least because they are rarely discussed in English.

The film is directed by Eloy de la Iglesia from a screenplay by the director and Gonzalo Goicoechea. De la Iglesia is perhaps best known for films “about young urban marginality and delinquency in what was commonly called cine quinqui” (see comment from ‘La Cinètika’ below). I haven’t seen any of these other films, but here he was taking advantage of the lifting of film censorship in Spain to explore his own key identities as a socialist gay man. In one sense the film is linked to Pedro Almodóvar’s early films in the transition period, but the difference is that where Almodóvar was just beginning to learn his trade, de la Iglesia was already an experienced filmmaker whose credits as actor, writer and director went back to the 1960s.

The transition period sees the left in Spain trying to mobilise and to gain elected representatives in the Cortes. It sees alliances between Communists and more centrist parties (PSOE – Partido Socialista Obrero Español) which began to detach from Marxism in order to gain power). The narrative of El diputado sees a crisis developing for a youngish man who moves from being a ‘deputy’ in an underground Marxist party to becoming one of four party members elected to the Cortes and in the process the promise of becoming a future leader. He has a major weakness (in political terms) of being unable to put to one side his love for a young under-age man.

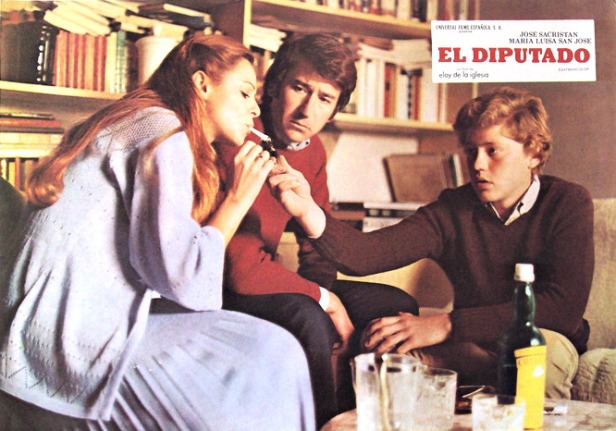

One aspect of the film is undoubtedly to explore and celebrate the gay scene in Madrid in the years immediately following Franco’s death. The central character Roberto Orbea (José Sacristán) – who I note has over 100 acting credits on IMDb – is a man of independent means (via a family inheritance) who is forced out of his academic position as a law professor and imprisoned. In prison he meets Nes (Ángel Pardo) who introduces him to gay sex and later sets him up with young boys. Roberto is bisexual and married to the beautiful Carmen (María Luisa San José) but he can’t put aside his attraction to young men. All this is presented as a flashback as Roberto agonises on how to act in a crisis. In the early years of the ‘transición‘, the communists begin to organise more openly and to hold public rallies. The fascists attempt to stop the left organising and when they discover Roberto’s ‘weakness’ they decide to exploit it through Juanito (José Luis Alonso), the minor who Roberto falls for in a big way.

I don’t want to spoil the narrative any further. Instead, I want to explore what de la Iglesia does with the story. The film was actually projected on 35mm, so Keith was there (and the very experienced HPPH projectionist had problems getting the aspect ratio correct, probably because the instructions on the cans wasn’t clear – we thought that perhaps it was meant to be 1.66:1 not 1.85:1). Keith thought that Roberto was surprisingly naïve for a Marxist lawyer in not realising what was likely to happen. I can see what he means, but I was struck by one of the (few) comments on IMDb which linked the film to Basil Dearden’s Victim (1961), a classic of British cinema in which Dirk Bogarde, a British matinee idol of the 1940s and 1950s, who risked all to play a married lawyer who is being blackmailed because of his affair with a young man. It’s an interesting reference, especially with the involvement of a loving wife. I think we have to accept that Roberto genuinely loves Juanito and can’t let him go – just as Carmen loves Roberto and can’t let him go. I think that de la Iglesia is quite clever in offering us the explict gay (and straight) sex which Roberto and Juanito enjoy, but also the demonstrations and campaign rallies that Juanito comes to enjoy and believe in. He also becomes something like a family member for Roberto and Carmen. de la Iglesia’s real coup though is to explore the class basis of the relationship. Roberto is a middle-class bourgeois Marxist (with the wealth to rent a flat as a secret HQ for the party and then as his love nest) who learns something about working-class families through his relationship with Juanito. Juanito is alienated from his own working-class community but discovers it again through his involvement with the young comrades from his neighbourhood during the demonstrations and political campaigns. Socialist/Marxist activists are often represented in films as socially conservative and this view of Roberto makes an interesting change.

The best scholarship on this film, and de la Inglesia’s work generally, that I’ve found is in Barry Jordan & Rikki Morgan-Tamosunas, Contemporary Spanish Cinema, Manchester University Press 1998. They emphasise Roberto’s struggle in which he “first denies and then conceals his own sexuality, believing it to be a deviant manifestation of bourgeois indulgence” (p. 149). They then recognise that the increased openness of socialist political campaigning is contrasted with the still clandestine gay world in which Roberto is active. He is “forced by the strength of his sexuality to recognise both its inevitability and the political right to live consistently with his identity”. I think that this is a perceptive reading but it doesn’t deal with two of the other major concerns of the narrative – when will Roberto tell his party about something which could be damaging if used by their enemies. And what will happen to Juanito (who is still a minor)?

I won’t spoil the narrative of this melodrama, except to say that it has both a dramatic climax and an ‘open’ ending, but I think that it is a film that manages to be ‘realistic’ and progressive in its representations while providing the dubious (but genuine) ‘pleasures’ of exploitation cinema. Thanks to Andy, Rachel and Jessie at HOME for making it possible to see the film in the UK.

Interesting commentary by Roy. I and Alan, the projectionist, actually thought the problem with the print was that it was a composite; so some reels were in 1.66:1 and some in 1.85:a: odd but neither ratio looked mis-projected.

I can see where Roy is coming from on the film. I thought the director was more interested in the gay aspects of the story than the political; hence the ;’naivety’ of the central character. And the wife was seriously underdeveloped.

The film seemed unsure whether the party in question was the Socialist or the Communist. As so often, the Marxism in the film was fairly simplistic.

There were some interesting posters and graphics in the mise en scene which I assume were actual examples.

LikeLike

First of all thanks for your site which I found really interesting. I just wanted to note that when you write “de la Iglesia is perhaps best known for a series of horror films” I fear you may be thinking on the current Alex de la Iglesia. While Eloy de la Iglesia had a few horror films in his career he is better known for his movies about young urban marginality and delinquency in what was commonly called “cine quinqui”.

LikeLike

Thanks for the correction. I wasn’t confusing the two directors (I’ve seen several Alex de la Iglesia films) but since I haven’t seen Eloy de la Iglesia’s other films (only a few released in the UK?), I simply went by the titles, some of which imply horror, but now I see are more like thrillers and social dramas. I’ve amended the post to include your description.

LikeLike