I’ve finally come across a Region B Blu-ray of this Truffaut film from his early peak period in the 1960s. I saw it a couple of times on TV in a ‘pan and scan’ presentation but it’s good to see it again in pristine form and the correct aspect ratio and to enjoy some of the extras, including a piece by Kent Jones and another by Barry Forshaw on the writer Cornell Woolrich in his guise as ‘William Irish’. The Blu-ray is from Radiance who usually find some excellent support material.

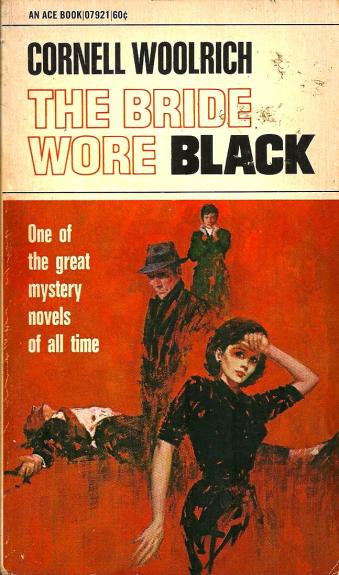

The film is understood to be Truffaut’s choice as a film for Jeanne Moreau as well as a much-needed opportunity to make money for Truffaut’s own production company Les Films du Carosse. He had already adapted a David Goodis novel for his 1960 film Tirez sur le pianiste and he was certainly interested in American pulp fiction. Some critics have also suggested that this is Truffaut’s attempt to make a Hitchcock hommage after his book of interviews with Hitchcock was published in 1966. Chabrol is generally seen as the nouvelle vague director who frequently channelled Hitchcock but there are several aspects of Truffaut’s film worth pointing out for Hitchcock references.

The film begins with a large print image of a naked Jeanne Moreau in medium close-up being reproduced several times and copies collected by a machine. We then see Julie (Moreau) dressed in black, flicking through a photo album before she attempts to end her life by leaping through a window, only to be stopped by her mother. Next we see her packing a suitcase with black and white clothes on top. She lays out five groups of banknotes on top of the case. We see her with her niece walking to a railway station and saying goodbye to the girl before getting on the train, but almost immediately getting out on the other side of the carriage and crossing the tracks. Throughout this sequence there is Bernard Herrmann’s score. I was shocked this time round to realise that both the scene depicting filling the suitcase and the walk down the platform are reminiscent of the opening sequence of Hitchcock’s Marnie (1964) and the music sequence itself includes a strings element that is very similar to the Marnie score. The two films do not have the same narrative but in these openings the two women are doing something very similar – setting off to do something which will mean changing their identity. We might argue that Marnie and Julie are both worthy of study by a psychoanalyst, something gradually revealed in each film.

Kent Jones posits a view that this film falls roughly half way between a typical Truffaut ‘art film’ and a genre picture. But Diana Holmes and Robert Ingram (1998) include the film as one of the four genre films Truffaut made in the 1960s – three crime films adapted from American crime novels and Fahrenheit 451 (1966) also adapted, but from Ray Bradbury’s science fiction novel. The central point about The Bride Wore Black is that Truffaut’s adaptation uses the genre elements but undermines the expectations of a Hollywood narrative. The opening introduces Julie Kohler but does not proceed like a crime film narrative. Rather like Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) in which the central character is killed part way through the narrative, Truffaut shows the shooting of Julie’s husband on the steps of the church, where the couple’s wedding has just been held, half way through his film thus taking away any mystery about what happened and also setting up Julie as an obsessive avenger of her husband’s death, even though it is now revealed as an accident. The audience then follows Julie on her mission for which she has no justification apart from her despair at losing her future. The narrative then offers no clear ‘resolution’ of Julie’s actions. In a later film like Une belle fille comme moi (1972) Truffaut will return to the behaviour of ‘criminal woman’ but use a sociological study to present his story. Stylistically The Bride Wore Black is a colour film with mainly high key lighting and as such is no film noir but Julie is literally a femme fatale. The five men she sets out to kill comprise a diverse group each of whom seems incapable of an equal relationship with a woman. They are all types of typical Truffaut ‘weak men’. Two are ‘womanisers’, one is lonely and lacking confidence, one brutish and another arrogant.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the narrative is the moral question about Julie’s behaviour. At least one of the commentators I’ve come across assumes that audiences will be shocked by Julie’s careful planning and cool ‘disposal’ of her victims. Personally it didn’t really occur to me as I watched the film. I think that this is possibly partly to do with Jeanne Moreau’s mesmerising performance. I was too busy admiring how she tackled the role to bother thinking about her as a killer. The broader question is whether this is simply a function of genre. If we accept that a film aims to tell a story that is structured as a conventional genre story rather than as a reflective discussion of a social issue, then our interest is more concerned with how it works as an example of the genre – how it presents the killer on a revenge mission, the details of each murder attempt, the reaction of the victims etc. In this case the generic conventions are there but Truffaut subverts them and presents us with a critical view of the conventional genre.

I think we could be critical of the film in that it doesn’t really give us any background into Julie’s family or her relationship with her husband of only a few moments. There is no sociological explanation, no psychoanalysis, we only see what happens ‘after the event’ of the husband’s death. Our pleasure is in observation of Julie’s plans and how she carries them out. In this respect, some of the scenarios do seem to be unlikely (i.e. nobody seems to notice what she is up to or to connect her with the deaths and the police don’t appear until much later). I’m not sure the lack of background or the plot flaws matter in this case but I can see that it might annoy some audiences.

In terms of the construction and presentation of the narrative, I enjoyed the Herrmann score and I didn’t feel there were any problems with Raoul Coutard’s camerawork – but there are claims that Truffaut was unhappy with the photography, possibly because this was the first time he and Coutard had worked together in colour. The other performances aside from Moreau are also very good and include a number of notable actors of the period who had already, or would later, appear in other Truffaut films (Jean-Claude Brialy, Michel Lonsdale, Charles Denner and Michel Bouqet). The adaptation of the original novel saw Truffaut working with Jean-Louis Richard, another who worked on other Truffaut films.

Perhaps I will return to this film at a later date and study it alongside Marnie and some of the Hitchcockian films of Claude Chabrol.

Reference

Holmes, Diana and Ingram, Robert (1998) François Truffaut, Manchester: Manchester University Press