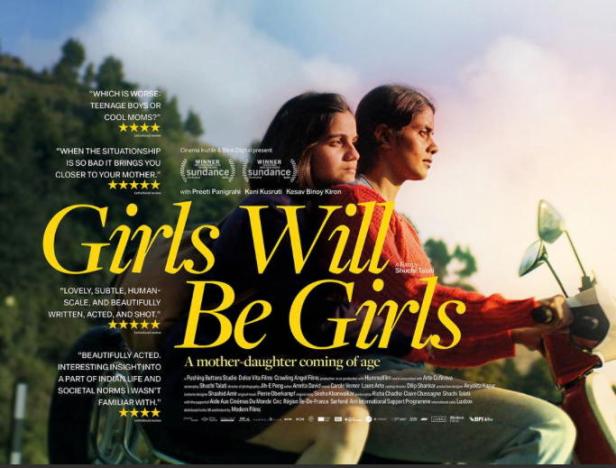

Girls Will Be Girls is an unusual film. Its subject matter seems familiar but it is presented in an original way. It’s also very good and I recommend it highly. This film joins two other recent ‘Indian Independents’ that are also co-productions in the form of All We Imagine as Light (France-India-Netherlands-Luxembourg 2024) and Santosh (India-UK-France-Germany 2024). All three films are strong personal statements by women. In this case, director Shuchi Talati trained at the American Film Institute after university in India and her film premiered at Sundance in 2024. Opening on general release in France, the UK, US and Australia, it seems to have been released online in India with its mainly English dialogue dubbed into Hindi.

The relevant generic category here is the ‘coming-of-age’ story, a very loose concept that might suggest a moment of transition in the life of a young person at any point from about thirteen up until the early twenties. The mix of elements might suggest ‘sexual awakening’ or a sense of discovery of identity or perhaps more generally an understanding of what it means to be an adult. In this case the director wanted to focus on the problems facing teenage girls in a society which she sees as being still very restrictive for young women. The setting is a strict boarding school in the Himalayan state of Uttarakhand. Mira (Preeti Panigrahi) is a 16 year-old girl who at the start of the narrative is chosen to be the ‘Head Prefect’ of the school because of her outstanding academic record and her seeming maturity. It is the first time a girl has been chosen for the role. Is this going to prove to be a great opportunity for Mira or is it a ‘poisoned chalice’? She will get to be close to the school’s head teacher Ms Bansal (Devika Shahani) but she will also possibly alienate many of her fellow students, especially if she tries to discipline them in any way. The school seems to follow British conventions in which Prefects are expected to keep order. It is an English-medium school and most of the students are likely to come from upper-middle class homes.

Mira seems to be in the odd situation of having a dormitory room which she shares with another student, Priya, but also the opportunity to stay with her mother Anila (Kana Kusruti) who appears to have rented a house close to the school. Mira’s father is away for much of the time on business(?). Mira’s relationship with her mother is in some ways similar to that with Ms Bansal. Having a supportive mother close by has many advantages but it is also possibly stifling at a time when Mira is trying to ‘find herself’. The third major player in the narrative is a new 17 year-old male student Srinivas (Kesav Binoy Kiron) who has arrived from an International School in Hong Kong. His father is a diplomat and Sri has earlier been at other International Schools. He is tall and handsome and, by contrast with the other students in Mira’s school, quite ‘worldly wise’ because of his exposure to different cultures. We assume very quickly that Mira and Sri will get together and that perhaps any relationship between them will see Mira either learning from or possibly being seduced, in more ways than one, by Sri. But it doesn’t quite work out that way.

Shuchi Talati, after a couple of well-regarded short films, decided to make this film using her own experiences of a similar boarding school and what she saw of the double standards that underpinned the approach to the difference between male and female students. As she puts it:

. . . girls are monitored, ostensibly to protect their ‘virtue’. Male sexuality is allowed to express itself, sometimes in the form of aggression toward girls, while we are instructed to be submissive and ashamed of our bodies. Despite this, I saw all around me strong, vibrant girls and women who subverted and circumvented social and moral codes. In Girls Will Be Girls, I wanted to write about these subversive women who populated my life, but never my screens, and to expand the narratives available to Indian women. Indian (and Western) films often erase female bodies. (from the Press Notes in French, translated by Google)

What makes this film very different is the presentation of Anila and the excellent performances of all three lead characters. Early on we learn that Anila went to a similar school as her daughter and that she married soon after without really having the chance to experience an adult world outside school. She is still a ‘young mother’ in one sense at 38 and she wants to make sure that Mira isn’t trapped in the same way: but she also finds her desire re-kindled by the culture of the school and the young men and women who inhabit it. When Mira and Sri start a relationship, Anila’s response is ambiguous. She seems intent on chaperoning her daughter while encouraging the couple to be together. Or does she find herself aroused by the handsome young man invited into her house? In a key scene Mira switches on the radio and a song is playing which Anila remembers and she begins to dance with Mira and Sri, eventually taking over as the leader of the dance, sidelining Mira. (The narrative takes place in the 1990s so there are no mobile phones and most students have a Walkman.)

It can’t be easy for Mira seeing her mother behave in this way but she tries to make the most of the opportunity to be with Sri in her mother’s house outside the school. However, she also has to contend with her position in the school and the antagonism of some of the other students. I think the script by Talati works well over nearly two hours – a long time for this kind of film. There are enough sequences in which we are alone with Mira as she reflects on her position and prepares her next move. There is a balance between the pressures of school life and life with her mother, both of which involve Sri. Everything works because of the casting and the performances. Preeti Panigrahi and Kesav Binoy Kiron both made their feature film debut in this film but Kana Kusruti became well established in Malayalam cinema in the 2010s. I was sure I’d seen her before and I remembered later that she had been the lead in one of the other two films I mentioned at the top of this posting, All We Imagine as Light. I think I didn’t recognise her immediately simply because the two roles are rather different. She is a commanding figure in both films but plays younger in this role. I would also like to mention the camerawork by Jih-E Peng. She is a Taiwanese cinematographer based in Los Angeles who may have met Shuchi Talati at the AFI. I suspect that having a woman behind the camera helped a great deal with some of the scenes. I liked the contrast between the open-ness of the school with the occasional long shots and the intimacy of other scenes, especially in Anila’s house. I’m not sure why the film was shot in the Academy ratio (1.37:1) but it works and perhaps reminds some audiences of earlier Indian films – I thought of Satyajit Ray’s Kanchenjungha (1962). (IMDb suggests it is 1.44:1 digital cinema can theoretically use any ratio.)

Girls Will Be Girls is an ironic twist on the often uttered phrase ‘boys will be boys’ with which young men are forgiven for sometimes misogynistic behaviour. The film is on other streamers as well as BFI Player so it is generally accessible. Here’s a trailer. I have emphasised that the film uses familiar narrative elements in sometimes surprising ways and it doesn’t offer the usual neat Hollywood ending – all the more reason to embrace it.