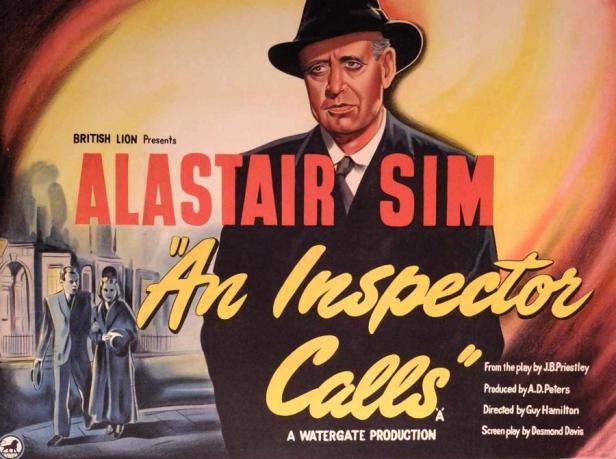

The film adaptation of J. B. Priestley’s 1945 stage play was released in 1954 and Studio Canal (which has a very large library of British films) released a new digital print of the film on Blu-ray and UHD a few weeks ago. The Priestley Society in the writer’s home city of Bradford organised a screening of the film at Pictureville in Bradford. The screening was introduced by Bill Lawrence on behalf of the Priestley Society. Bill told us of the large number of TV and film adaptations of the play – currently 23 and rising – from around the world. The original play seems to have become a genuine classic in the sense that it appears as the reference point for dozens of episodes of TV series exploring the basic idea of the narrative. An interesting question is why has the work travelled so well internationally? We’ll explore that question later. For now let’s consider this 1954 version.

The film was produced independently for what might be considered as the third player in the British film industry of the early 1950s. The industry was dominated by the two vertically integrated companies, Rank and Associated British. British Lion had existed in various forms since 1918 but after falling under the control of Alexander Korda in 1945 it had to be rescued by the Labour government through the formation of the National Film Finance Corporation and in 1954 the company actually went into receivership before continuing operations in the form of two new companies. British Lion was in effect the third major distributor in the UK and also operated Shepperton Studios. An Inspector Calls was produced by an independent company created specifically for the production with the unfortunate name of ‘Watergate Productions Ltd.’ Priestley might have enjoyed the irony of that name? He died in 1984 so would have been aware of Richard Nixon.

The production is very much studio set, which is an important part of the claustrophobia of a group of characters facing a form of inquisition. The narrative is set in 1912 in the household of a successful factory owner in the town of ‘Brumley’, presumably meant to be in the industrial North or Midlands. That date arguably marks the height of British Imperialism, after which decline sets in. Mr. Birling (Arthur Young) and his wife (Olga Lindo) are examples of the new upper middle-class who have challenged the landed gentry as the leaders of Edwardian England and they are full of their own importance and proud of their ‘respectability’. They are holding a formal dinner party to welcome their daughter Sheila’s ‘young man’ Gerald Croft, son of a distinguished local family who they expect to propose to their daughter soon. Gerald (Brian Worth) and Sheila (Eileen Moore) are the young couple brimming with vitality and expected to advance their wealth and position in society. The other family member around the table is Eric Berling (Bryan Forbes) who is drinking too much and behaving ‘badly’ at a time when his parents expect him to support his sister. Even so the dinner appears to be going well before the sudden appearance of the mysterious Inspector Poole (the name is slightly changed from the original ‘Goole’). The Inspector is played by Alastair Sim at the height of his powers. Here he underplays his normal persona of the wide-eyed and possibly jovial but also anxious centre of attention. He is calm and serious and claims to be investigating the death of a young woman, Eva Smith (Jane Wenham). He turns first to Mr. Birling asking him if he remembers Miss Smith? When Birling blusters, Poole reminds him that she once worked in his factory. At this point, a flashback reveals how Eva became a ‘problem worker’ and was dismissed. The investigation then turns to Sheila and a second flashback ensues. We realise that all five people around the table are going to relive the incident in which they did or didn’t do something which contributed to the demise of a young woman who over time changed her name a couple of times. The seemingly omniscient Inspector Poole unnerves everyone but I won’t spoil the narrative just in case you don’t know the story. There is a final twist to the tale but overall the prosperous and respectable family is made to recognise the damage that it has done.

The film is directed by Guy Hamilton who would become well known in the 1960s and 1970s as the director of four James Bond films as well as other ‘prestige’ British pictures. Hamilton chose his projects carefully and took his time, making only 22 features in a long career. But most of his films were successful at the box office. An Inspector Calls was early in his career as a director but he had plenty of experience as an assistant director on many important British films between 1947 and 1952, including on three Carol Reed productions. His mini-bio on IMDb suggests that as the son of a British diplomat and born in France where he spent his holidays as a youth before getting some experience as a clapperboard operator at the Victorine Studios in Nice, he became a fan of Jean Renoir in the 1930s. If so he may well have imbibed some of Renoir’s views which would have helped him think about Priestley’s play. Ted Scaife is the DoP, Alan Osbiston the editor and Joseph Bato the art director. This was an experienced crew and they brought in a very well-made film running a tight 80 minutes.The only directly expressionist elements I noted on the Pictureville screen were the noirish staircase scenes which would have been standard for the period.

The performances are all very good. Sim is the dominant figure as might be expected but I was also impressed by the three younger players, Eileen Moore as Sheila, Bryan Forbes as Eric and Jane Wenham as Eva in the flashbacks. Eileen Moore presents as a tall and very attractive young woman with an assertive manner (at least early in the narrative). She was barely 21 when filming began and married George Cole (who had the small part of a tram conductor) in 1954. But whereas Cole had a very long career with over 150 credits, Eileen’s career was over by the late 1960s and much of it was based in TV productions. It seems a shame that her talent wasn’t used in more parts – perhaps she retired early like several other women of her generation. Jane Wenham was a few years older. Perhaps not so conventionally beautiful she had a distinctive, characterful appearance, but like Moore she was early into TV productions and didn’t appear in many cinema films in a long career. She was briefly married to Albert Finney from 1957 t0 1961. Bryan Forbes was in some ways a central figure during the slow decline of British cinema from its 1946 peak. He began as an actor after military service appearing in films from 1949 up to the early 1960s on quite a regular basis, but he was also a writer from 1954 and a director from 1961. He was occasionally a producer and from 1970 to 1971 he was Head of Production at EMI Films after the takeover of ABPC. Eric is quite a difficult role but I think he pulls it off well.

This film version of An Inspector Calls is a good example of the commercial British film of its time, technically excellent and beautifully performed. Allied to the strong original material of the Priestley play, it is both enjoyable and impressive. So why are there so many productions of the play across the world since its 1945 première (in the Soviet Union in Moscow and Leningrad)? The clue is partly in those Russian premières (at a time when there was a queue of new productions jostling for an opening in the West End). Priestley was a left-wing thinker and writer who during the Second World War was a founder of one of the socialist parties, Common Wealth, which though adopting similar policies to Labour, decided to contest elections when the wartime coalition government was faced with by-elections. When the coalition parties themselves sought to allow unopposed candidates, Common Wealth was able to win parliamentary seats. Priestley, however soon disassociated himself from Common Wealth. During the war he was a very popular broadcaster as well as writer but was eventually barred by the BBC because of his political views. In 1944, before the first performances of An Inspector Calls, Priestley wrote a play and adapted it as the film They Came to a City (1944) directed by Basil Dearden at Ealing. It includes an appearance by Priestley himself in a framing story for what is a fantasy about a group of people, a small group ‘cross section’ of the UK population, who are taken to a city which appears to be something like a socialist Utopia. The members of the group react in different ways and discuss their feelings and thoughts. Priestley intended the film as something that might stimulate discussion of what British society might look like after the war ended.

Through his novels and plays, Priestley had an international audience and it isn’t difficult to see why in the post-war world, in countries like India or in Eastern Europe like Czechoslovakia, audiences could easily recognise their own society’s failings. In the UK, the play would fall out of favour in the late 1950s as the contemporary plays of a new generation gradually took over the West End. But it survived in school curricula and was boosted by a new staging in 1992 at the National Theatre in 1992 and a national touring production in 2011-12. In the April 1954 Monthly Film Bulletin, the reviewer thought it surprising to choose material that presented stereotypical characters in a story that drove home a moral in a monotonous way, but they did admit that the use of flashbacks worked well and the performances were good. I suppose that view was par for the reviewing culture of the time. I think that viewed in 2024, the moral tale about wealth, respectability and responsibility is still worth exploring – perhaps even more so.