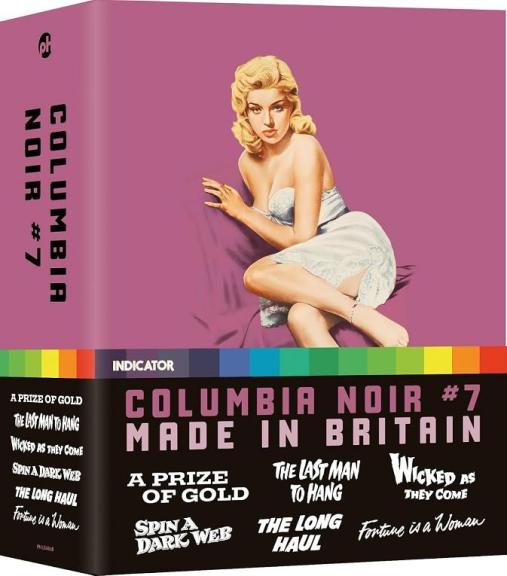

This time as soon as I heard about Indicator’s latest ‘Columbia Noir’ box set, I preordered it. I’ve enjoyed watching the six British films in the collection over Christmas. The earliest film in the collection is A Prize of Gold from 1955, a film I watched half of a few years ago on Talking Pictures TV so I was grateful to get the chance to watch the whole film.

From the late 1940s to the mid-1950s there seemed to be a much more fluid relationship between American and British film producers than exists now (when US domination is more pronounced but there are possibly more opportunities for British actors in the US). Warwick Films was the brainchild of the American producers Irving Allen and Alfred R. (‘Cubby’) Broccoli. They intended to make films with at least one major American star in the UK to take advantage of fiscal policies in both the US and UK. The films were ‘British’ but intended for an international market and distributed in major territories by Columbia. The company was in operation between 1951 and 1960. Later Cubby Broccoli produced the James Bond films of the 1960s. When Irving Allen turned down the chance to adapt Fleming’s Bond books, Broccoli teamed up with Harry Saltzman in Eon Productions. Broccoli’s experience with Warwick’s overseas productions was no doubt very useful.

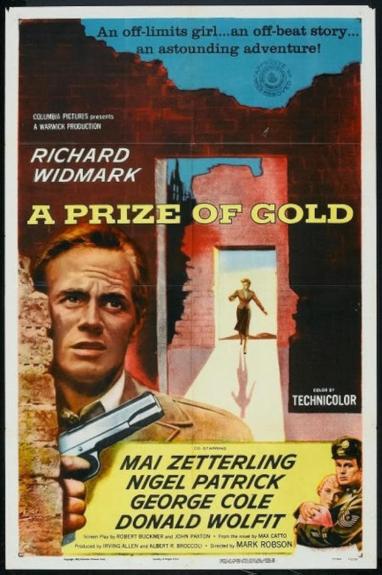

A Prize of Gold opens with the discovery of a cache of gold bars dredged up by a river maintenance team in West Berlin. The Allied Occupation authorities are alerted as it is most likely ‘Nazi gold’ and Anglo-American co-operation sees two military police sergeants, Joe Lawrence (Richard Widmark) and Roger Morris (George Cole) assigned to begin the process of removing the gold to London. Before they can get properly started, however, the pair manage to have their jeep stolen by a young teenage boy and recovering the wrecked vehicle finds them at a school for street children organised amongst bombed-out buildings by Maria (Mai Zetterling). Already I am intrigued by this mixture of elements.

First, there is the intrigue of pairing Richard Widmark with George Cole. Widmark in the early part of his career was often cast as the psychopath or the hard man but here he is more of a jack-the-lad character and this is confirmed by pairing him with George Cole. Cole would be very familiar to British audiences but his developing persona would be unknown to US audiences. The year before he had worked on the first St. Trinians film as ‘Flash Harry’, perhaps his best-known early ‘spiv’ role. (The ‘spiv’ was a British character associated with petty criminality, mainly dealing in ‘black market’ goods in wartime and post-war austerity in the 1940-1950s.) The comic potential is emphasised by having Joe replace his jeep with the comical little Messerschmitt bubble car which was first introduced in 1955. The plot of the film goes through several leaps of imagination to develop its story. When Joe and Roger chase the boy in the jeep, he abandons the vehicle when it crashes and sets out across the bomb sites. This is a reminder of the German films (mainly East German) set in the ‘rubble’ of bombed-out Berlin and known as ‘Trümmerfilme”. Roberto Rossellini had made one of the first internationally distributed films of this type with Germany Year Zero in 1948. The desolation of the ruins is to some extent negated by the Technicolor photography – Warwick being concerned to present their films in the attractive and modern mode rather than the usual black & white for a crime story of this kind. Colour also works against the possible noir connotations of the film – more on that later. The boy (Andrew Ray) is a refugee child, part of the group looked after by Maria. Her aim is to take the children to Brazil to start a new life. Joe’s intervention will cause some problems as he alienates the wealthy man who planned to pay for the trip – thus creating the need for cash and Joe’s turn to crime.

The plot develops with Widmark’s Joe pursuing both Maria and the idea of stealing the gold. This means some comic business with Joe ‘borrowing’ his senior officers uniform at one point and then meeting Roger’s contacts in London who will help in receiving the stolen gold and then fence it. The London contacts include an ex-RAF officer, Brian, who can fly the DC-3 carrying the gold. This character is played by Nigel Patrick with some gusto, matching that of other officer types turning to criminal activity in other post-war UK various films (such as David Farrar’s RAF officer in Ealing’s Cage of Gold (UK 1950). He’s matched by the great Shakespearean actor Donald Wolfit as the fence (in a Rolls-Royce) and Joseph Tomelty as Roger’s uncle, the mechanic.

The film narrative was adapted from the 1953 novel by Max Catto, a prolific Manchester-born writer whose work (novels and screenplays) formed the basis for several films including Ealing’s West of Zanzibar (UK 1954) and Carol Reed’s Trapeze (US 1956). The director was Mark Robson who had begun his directorial career under Val Lewton at RKO in 1943 and became a front-line Hollywood director. Wikipedia’s page on the film suggests that the production budget was just over £200,000 and Kinematograph Weekly picks out the film as doing “outstanding business” for Columbia ahead of the studio’s CinemaScope releases in 1955. A Prize of Gold on the Indicator Blu-ray is presented in a 1.75:1 ratio rather than ‘Scope (still on 2.55:1 at this point). The 1.75:1 ratio is unusual but seems to be quite common for UK films at this time. ‘Scope was not feasible in all cinemas without alterations to the auditorium and this format was perhaps the best compromise – although 1.66:1 was becoming the standard in Europe and for some UK producers. A Prize of Gold was an ‘A’ feature in UK cinemas, running at 98 minutes.

The Indicator disc carries several ‘extras’ as well as a couple of printed essays in the booklet as part of the box set. One of these by Jonathan Bygraves neatly analyses parts of the narrative but makes one odd mistake. He describes both the British and American leads as playing ‘officers’ but both are in fact Military Police Sergeants, i.e. NCOs (non-commissioned officers). This is quite an important distinction in class terms. The Nigel Patrick character is an RAF officer – all pilots were officers. The distinction between Joe/Roger and Brian becomes important in the last section of the film. On the disc there is an audio commentary by Thirza Wakefield and the eminent British Cinema scholar Melanie Williams as well as a separate interview with Lies Lanckman of the University of the West of England. Lanckman is the one pushing for this title to be included within the category of ‘film noir‘. I think this is a bit of a stretch in aesthetic terms. The British scenes filmed at Shepperton and on London locations certainly suggest the noir city, but West Berlin is presented in Technicolor with limited night-time scenes. Lanckman suggests the narrative is set in the late 1940s but the Messerschmitt car nixes that – unless of course the anachronism is simply a mistake rather than deliberate. Where Lackman is correct is to recognise that Maria and Joe do have some correspondence to the femme fatale and the ‘doomed man’, though she doesn’t seduce him with gold robbery in mind and his decision to steal it is prompted by a good deed (he’ll give the Nazi money to Maria and the children). Brian is certainly a familiar post-war British character who could be related to American characters who ‘go bad’ because of the lack of excitement and the lack of freedom to act that repressed many ex-military characters in the conservative 1950s. These are some of the possible noir elements but I’m not sure they are enough for me to justify its place in a noir boxset. If your categorisation of noir is much broader you may think differently.

Mai Zetterling is referred to as a ‘starlet’ at one point in the audio commentary which is a little misleading at best. Perhaps it’s a term attempting simply to indicate that she’s not an A List leading actor, but in the context of Rank in the early 1950s it’s rather insulting as it suggests that she was part of the Rank ‘Charm School’ of conformist young actors. She herself refers to being just one of the unhappy contractees at Rank between 1948 and 1951. But that was a few years earlier. In 1955 she was 30 and had experience of working on the stage in Sweden, the UK and on Broadway. She had made a successful Hollywood film playing opposite Danny Kaye a few years earlier. She realised early on that she didn’t think much of the way the film industry tried to create stars. Later she would become one of the first feminist filmmakers directing films in Sweden, France and the UK. All this is laid out in her autobiography All Those Tomorrows (1985). What is true is that she was rather fed up of being given parts in which she played a refugee and especially a young German woman. See my post on Portrait From Life (UK 1949) for more on this. She took the role in A Prize of Gold because she needed the money but she is very good as always. I think she was a bit like Ida Lupino in often being the best thing in films that overall weren’t up to much. In this case, however, the other leads are fine as well and this is an entertaining and enjoyable film that is very well made. There is music by Malcolm Arnold and this is the first feature for cinematographer Ted Moore after operator duties on several earlier films. He would go on to shoot most of the Bond films with Sean Connery and several other major films in the 1960s. I have been impressed with the films made by Warwick and I’ve a couple more to watch. Columbia’s faith in the film is indicated by an opening at the Odeon Leicester Square, arguably the most prestigious cinema in the UK in 1955 (and still today).