This strange little film starts brightly but ends in a rush, probably because it is so short at around 70 minutes for the cinema print and only 68 minutes for the TV version I watched on Talking Pictures TV. The production context is interesting. In the early 1950s there appears to have been a surge in demand for second features in the UK, largely I’m guessing because some of the Hollywood studios had ceased to make ‘B’ pictures. A second reason might be that US TV stations, denied access to studio film libraries, looked to independent producers in the UK. The outcome was that for a few years there were several small studios around London making material for the American market which might also get into UK cinemas.

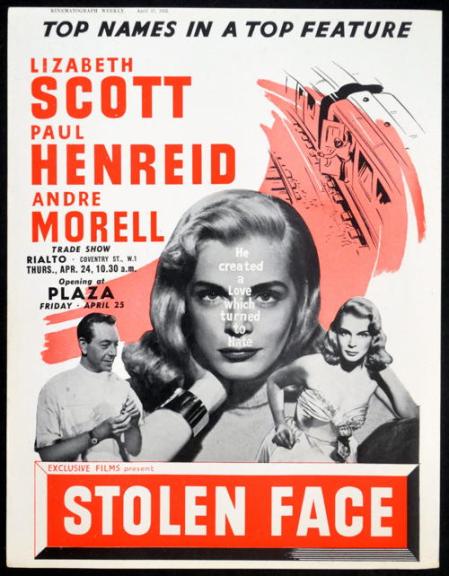

In this case the US independent producer Robert L. Lippert set up a deal with James Carreras of Exclusive Films (which was later known as Hammer Films). Lippert supplied American stars for otherwise completely British productions. There was a belief at the time that low budget British films needed an American star to gain audience attention. This film was produced at the Riverside Studios in Hammersmith. It was directed by Terence Fisher who was already well-established as a director but would find wider fame as a director of Hammer Horror films. The two Americans in this case were Paul Henreid and Lizabeth Scott. Henreid, the Austrian emigré star of Now Voyager and Casablanca had actually worked in the UK in the late 1930s after fleeing the Nazis. Scott was a younger actor who became associated with Hal Wallis Productions and when Wallis worked with Paramount she appeared in a number of late films noir in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Her career was relatively short. Henreid had a long career but at this point he was blacklisted by the major studios in Hollywood and like many American actors (and writers and directors) he was prepared to come to the UK. Scott was released by Wallis for this film.

The opening of the film focuses on Henreid as a top plastic surgeon Dr Philip Ritter, working out of Harley Street. He is clearly bored by the prospect of more face lifts for aging wealthy women despite the handsome fees they might pay. Instead, he seeks out pro bono cases. But either way he is working too hard and he accepts the advice of his partner in the practice and decides to take a holiday. He finds himself staying in a country pub but he can’t sleep because of the coughing next door. The cough belongs to Alice Brent (Lizabeth Scott), an American concert pianist with a heavy cold. The couple have a few days for her to recover and him to be captivated by her. It’s a simple set-up but the Hollywood stars play it well. It’s the second part of the narrative that is trickier. They are clearly attracted to each other but she turns him down and goes off to her European tour with her fiancé. Ritter’s reaction is over the top. He returns to his pro bono work and agrees to reconstruct the face of a female prisoner disfigured by wartime bombing after the prison doctor argues that it may help her to come to terms with who she is and to break the cycle of criminal behaviour that leads to incarceration. This is fine as an experiment but Ritter goes too far when he remodels the woman’s face to resemble Alice. When he has completed the complex project and discovers he has cloned the face successfully, he goes a step further and decides he will marry the woman (who appears to be on the verge of release!). You can probably write the rest of the script yourself. Ritter makes her look exactly like Alice and this means that Lizabeth Scott can play her as well with the original actor dubbing Scott’s voice. At this point I want to question the direct American involvement in the production.

The original story was written by two men born in Budapest but the screenplay was by two younger New Yorkers. I’m not sure they understood the class distinctions in the UK. Ritter foolishly takes his new wife to the opera and is then surprised that she is bored. She demands to leave and go to a jazz club (I think it was shot at Ronnie Scott’s and Scott and Jack Parnell play in the club). The woman Lily is discussed as a ‘psychopath’. I’m not sure this is the case but if you give a working-class woman a charge account in an upmarket store it’s a big temptation to spend the money or to walk off without charging it to the account. Ritter is warned by the prison doctor that perhaps she needs to see a psychiatrist. The same doctor has also told Ritter that only one prisoner he has previously helped has returned to a life of crime. Ritter is just too keen to turn her into Alice and she quite reasonably resists. When Alice returns from Europe and the two women meet on a train and Alice discovers Lily and Ritter together, the end is inevitable.

One of the issues for contemporary film scholars is to decide how films are categorised and how this changes over time. Inevitably when film noir became a popular tag this film was added to that category even though it doesn’t really fit. It’s not a noir for me but I can see the Scott connection and there is at least one similar noir in Dark Passage (US 1947) with Bogart and Bacall that involves plastic surgery and a change of identity. The connection to Hammer in this film possibly suggests horror and indeed there are examples of horror films such as The Hands of Orlac (UK-France 1960) which shares some elements with this film. In addition Terence Fisher went on to direct Hammer’s film The Curse of Frankenstein (UK 1957). Other suggestions are that the film prefigures Hitchcock’s Vertigo (US 1957). But again in a UK context there is The Seventh Veil (UK 1946) in which James Mason tries to take control of Ann Todd’s concert pianist. Finally, given the miraculous transformation carried out by the plastic surgeon there have been suggestions that this film is linked to the science fiction films also a genre explored by Hammer in the 1950s. Personally, I think we have to ask who ‘stole’ the face? Ritter is obsessed with Alice and perhaps unaware of the danger of this particular project. He’s not the saint but the real villain of the story and he should see the psychiatrist?

I think it is a shame the narrative collapses. What happens in the first section of the narrative works very well with some useful location shots . The music is by Malcolm Arnold and I recognised a couple of Hammer names on the crew list. An oddity about this production is that it received a West End release at the Plaza, Paramount’s showcase cinema on Lower Regent Street. Here it could be found programmed with the Paramount Western Denver & Rio Grande (US 1952) in early May. The package was presumably agreed between Paramount, Wallis and Lippert. On wide release via GFD, it was often with the Universal comedy melodrama Has Anybody Seen My Gal? (US 1952) directed by Douglas Sirk. I noted that the Synopsis on the American Film Institute Catalog page is riddled with mistakes. For instance, Ritter does not ‘bribe’ sales staff in department stores, he simply pays for the items that Lily took. On the train Ritter does not have a ‘private car’. He is in a First Class carriage but the older couple leave when Lily appears because of her behaviour. I have no problem with Hollywood co-productions as such but they could be more sensitive to British culture (even when it is more ‘stuffy’).

Here’s a clip from a recent Hammer restoration of the film:

i also quite enjoyed this film on Talking Pictures, perhaps a year ago now. Scott’s star was not quite in the ascendant at the time owing to persistent rumours of lesbianism, I believe, which may account for her journey across the pond, although she was one of several American stars (Carole Landis included) who sought a new start in the UK at the time. Scott did very well in two contrasting roles and her subsequent decline must be considered disappointing, as was the very rushed climax to this particular film.

LikeLike