The 2025 edition of this important festival ran from October 4th to the 11th. As usual it took place in Pordenone; the town was a little wet and chilly to start with but then the weather brightened up and we enjoyed warm sunshine. The majority of the screenings were in the Teatro Verdi, which was mainly full with just over 1,000 guests registered and frequently joined by local citizens. There is a large selection of photographs on Flickr webpages by Valerio Greco.

The Festival offered a strong and varied selection of titles from early cinema; including many that I had never seen before, or even was aware of. The majority of the screenings were from digital transfers, generally well done. There were only nine features screened from 35mm prints with quite a number of prints among the shorter titles. As always the screening enjoyed the accompaniment of the Festival team of musicians and a number of events with orchestral accompaniments.

The opening evening presented the 1922 Italian Cirano di Bergerac; adapted from the famous play by Edmund Rostand and directed by Augusto Genina and Mario Camerini. The digital transfer had retrained the stencil colour of the original. Restored in 2023 this version used titles based on Rostand’s play. This looked good though I feel that digital does not quite capture the stencil colour palette. The adaptation was well filmed with some flamboyant scenes. Pierre Magnier’s Cyrano was excellent: I thought Linda Moglia’s Rosanna developed as the film progressed: and Angelo Ferrari’s Christian was the most sympathetic of the adaptations I have seen. The music score, composed by Kurt Kuenne and performed by the Orchestra da Camera di Pordenone, served the movie well.

At the end as the conductor (Ben Palmer) and composer enjoyed the audience applause they pointed to the screen, a frequent gesture here. It was blank. I hope the director remembers my suggestion that they re-introduce the practice in the old Verdi when, following a special event film, a picture of the director or star appeared on the screen.

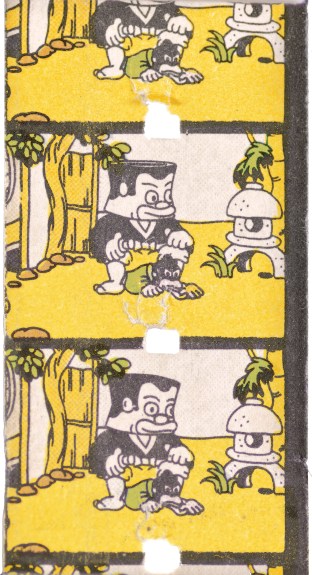

On the Sunday afternoon we had a presentation of Japanese Paper Prints. These were not the equivalent of the US copyright prints but a home screening system.

From 1932 to 1938, several Japanese companies produced films on paper rather than celluloid. These films used proprietary epidiascopic projectors for home and neighborhood screenings, capable of screening both opaque and transparent materials. The projectors reflected light off of an opaque film-strip into a lens which then projected the image onto a screen. Individual films were sold in popular department stores, or could be ordered direct via mail catalogue. Films came in lengths of 15, 30, or 45 metres, running about 1-3 minutes, although some films continued across multiple reels. The projectors were hand-cranked, so there was no set projection speed. Films included animé and live-action films (duplicated from celluloid sources), came in black & white and colour, and some films even had original soundtracks supplied on 78 rpm discs that synchronised with the film. The soundtracks featured music, sound effects, and dialogue, or Japanese narrators called benshi.” (Festival Catalogue).

We not only try to incorporate kinds of music that were commonly heard in the era – popular songs, jazz, and folk melodies – but in live-action chambara (Japanese swordplay) films, the koto quotes directly from classical pieces composed in the Edo (1603-1867) and Meiji (1868-1912) periods that depict battle scenes. We also utilise some sound effects and percussive sounds, because Japanese music in general is more open to what Western classical music may consider “noise.” (The Musicians commenting in the Festival Catalogue).

Wednesday evening saw a programme of digitised material from World War I. First we had The German Retreat and the Battle of Arras provided by the Imperial War Museums. This was a feature length documentary of a British Army offensive in 1917. It was one of three such treatments of Army battles, in this case produced by the Topical Film Company for the War Office Cinematograph Committee. The cameramen included the well-known Geoffrey Malins. The filming includes not just trench warfare, but battle preparation and artillery barrages: the wastelands produced by the war: and the British offensive. There is a much greater sense of battlefield space than in the earlier Battle of the Somme. This screening had an orchestral accompaniment together with a recorded choir. The composer Laura Rossi used both poems and songs from the period including some written by soldiers. The music echoes the point-of-view of the British soldiers and there is none of the more critical voices like Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfrid Owen.

The following screening was a cine-concerts with a different approach to accompaniment. Palestine – A Revised Narrative used newsreel footage in Palestine during the World War I with a soundscape of music by Cynthia Zaven at a ‘prepared piano’ and a sound design by Rana Eid. The newsreel footage was edited from the Imperial War Museum digitized collection. In the Catalogue Cynthia Zaven wrote about her and her colleagues approach to the accompaniment;

I had seen many photographs of Palestine dating back to the late 19th century, but I had never before watched actual film footage from that era, captured throughout the land – from Gaza and Jerusalem to Bethlehem, Nazareth, and Jaffa. Discovering this material was overwhelming. Although most of it was propaganda for the British Army fighting the Ottomans, some of the scenes of the diverse communities of Muslims, Christians, and Jews and their everyday lives was particularly moving. Especially at a time when those very images of co-existence were being erased, and Gaza eradicated.” (Festival Catalogue)

After viewing the 77 clips, varied in content and spanning 4 years (1914-18), I began selecting those that resonated with the project most. One question remained, however: What did it mean to look at the past through images shaped by the colonizer’s gaze?” The performance Cynthia Zaven and Rana Eid, met with warm applause by the audience, gave a poetic answer to that final question. [There is a short video of the two musicians on You Tube among the Giornate del Cinema Muto clips; including Cynthia Zaven ‘preparing’ the piano].

As well as the special events there were a series of programmes of silent films. Following on from last year there were the digitised versions of Biograph Paper Prints which acted as copyright material in the early years of US cinema. D. W. Griffith was the seminal pioneering director at Biograph from 1908 onwards. This was an opportunity to revisit his earliest titles. The Catalogue notes noted,

It is 1908 and Griffith has to crank out two films a week. Watching 1908 Biographs is like a miner, digging for emeralds.” (Festival Catalogue)

But along with technical innovations Griffith was exploring melodrama on film. And even basic films running only around ten to fifteen minutes have fascinating dramatic plots. So we had the contradictory representation of a Native American in The Call of the Wild, treated with some sympathy but still as the ‘other’. Griffith first essay into a Civil War drama, The Guerrilla, which was to become central to his most famous or infamous works. And The Song of the Shirt, where the differing experience of class rely on a Thomas Hood poem to depict the travails of exploitation and poverty.

There were series of titles featuring an Italian ‘diva’, Almirante Manzini, working in the teens and the 1920s. The features tended to be rather challenging as most were incomplete, often missing hundreds of metres of footage. So, at times, I was hard put to follow all the characters and their plot lines. However, the final screening, L’Ombra / The Shadow (1925) was complete and enabled one to enjoy her powerful screen presence. In this title she plays a wife who is struck by paralysis and chained to a chair under the care of a nursemaid. Predictably the husband has an affair, with a close friend of the wife. Miraculously the wife recovers and discovers the affair. By the narrative’s end she is reunited with a remorseful husband and is caring for his illegitimate child.

There were four child-centred films produced in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. Film-making here in the late 1920s was among the most committed of Socialist films. The Three / Troye (1928) is a film that features the Young Pioneers, Vladimir Lenin All-Union Pioneer Organisation, a Soviet youth organisation noted for its camps. The three young boys are the son of a proletarian family active in the Pioneers: a homeless boy with a pet rat: and the son of a Nepman [who were businesspeople in the early Soviet Union who took advantage of the opportunities for commercial trade and commodity manufacturing provided under the New Economic Policy]. All three take rather different trips to Siberia where there is also a Pioneer camp. There are some quite extravagant adventures; part of which are modelled on O. Henry’s short story ‘The Ramson of the Red Chief’, but all ends well at the Pioneer’s camp. One that I caught was Robinson on his own/Sam sobi Robinzon, 1929. It was directed by Lazar Frenkel who co-scripted the film with Valentyn Devyatnin. Digitised from a 35mm negative, this version was missing about 1500 feet, though the narrative was still coherent. Young Robinson is a book worm and fantasises about the adventure stories that he reads. This marks him out from his fellow schools student, mostly active in the Young Pioneers, Robinson goes off into the countryside in an exploration and gets into a number of scrapes. It it the Pioneers who rescue him and he joins them in their camp. This feature was great fun and had some notable visual treats, Soviet style.

Of particular interest were two features based on the classic British melodrama ‘East Lynne’ by Mrs Henry Wood. Famous as a story of mother love and loss, with a memorable line – ‘Dead!… dead!…and never called me Mother!’. As the Catalogue points out, this is a line added to the plot in a theatrical adaptation. There were numerous of these as well as a number of film versions. We enjoyed the British East Lynne from the Barker Motion Photography Company in 1913: a very early example of a six-reel feature. The surviving version, digitised from a nitrate 35mm print is missing more than a whole reel, but retains a fairly clear narrative though this is transposed from the 1861 to the 1840s. This ‘sensational novel’ provides murder, false accusations, intrigue, adultery, mystery and a final tragic loss. The film also offers some intriguing historical representations with an electoral hustings from the 1840s. Some of the populace for this events carried placards for the ‘Charter’ (The People’s Charter of 1838) and against the ‘Window Tax’ [an early British property tax imposed from 1696 to 1851]. Filmed in fairly full mid-shot it has one notable close-up, a clue to the murder, and some effective editing between the characters actions. [See Bioscope review where it was presented earlier in the year].

We then had a 1925 U.S. version from the Fox Film Corporation in a 35mm print. This enjoyed higher production values than that of the British and was almost complete. However, it made more changes to the original narrative and tried to inject some inappropriate humour. It did though fill out the characters from the novel, whereas the British adaptation offered fairly stereotypical melodramatic characters. To round off the study there was a fragment from a 1919 Max Sennett parody, East Lynne with Variations. Rather sending up the novel directly it offers a theatre company enacting stereotypical melodramatic roles.

The Canon Revisited offered some familiar classics like Fritz Lang’s Der müde Tod, but also two new titles. Love and Duty / Lian’ai yu yiwu was a melodrama from the Min Xin Film Co. in Shanghai, 1931. It starred the famous tragedienne Ruan Linyu, some of whose films we enjoyed at a previous Giornate.

And there was Are Parents People?, A Paramount Picture and comedy. It was directed by Malcolm St. Clair, an adaptation of a Saturday Evening Post story. The feature stars Adolphe Menjou [always a pleasure}, and Florence Vidor, as a couple considering divorce. But their daughter, played by Betty Bronson has other ideas.

It’s a film of visuals, propelled through expressions, gestures, situations, and physical posture, handled with economy and wit, not laden with dialogue.” (Catherine A. Surowiec in the Festival Catalogue),

The DCP, taken from a 16mm copy, was incomplete but the narrative progressed happily, even with some gaps.

Then there were Rediscoveries and Restorations with the 1927 The Blood Ship. [featured in the Festival Lobby card, though a publicity shot rather than a still].

This was well adapted from a contemporary novel by Fred Myton and directed by George B. Seitz. But an important figure in the production was leading actor Hobart Bosworth. He originally acquired the rights to the novel for his now defunct production company. And the story clearly fitted into his film persona. At and earlier Giornate we had him starring in the 1919 Behind the Door. In that film he plays a widower who tracks down the German submarine captain who kidnapped, raped and killed his wife. In this feature Bosworth signs on to The Golden Bough in order to wreak revenge on the captain, who sent him to prison and purloined his wife and daughter. As James Newman Bosworth is a member of a shanghaied crew who finally overcome the brutal captain and first officer. The cast includes an unusually positive representation of The Negro (Blue Washington) of whom the The Afro-American commented,

There was an uncanny sincerity in Washington’s acting that made those who viewed the picture feel they were really living the experiences with him. (Quoted in the Festival catalogue).

Much of the production was filmed on an actual three-masted clipper by cinematographer J. O. Taylor who had worked ion some of Bosworth’s earlier maritime features. The DCP, taken from a 35mm original, was a little shorter than the original but the narrative was clear enough.

Also included was the much heralded ‘lost’ John Ford early feature, The Scarlet Drop (1918). This was an incomplete version, digitised from a 35mm print with Spanish titles and running 41 minutes. About half the film is missing and apart from translation [in English subtitles] characters names have changed making the narrative a challenge. The basic story is of a family feud on the eve of the US Civil War. This is one of the films Harry Carey made with the young John Ford. He plays “Kentuck” from a ‘white trash’ household. The feud is with the affluent Calvert family. In the course of the movie we encounter the Quantrill raiders, a kidnapping, blackmail, miscegenation and a final climatic fight. The ‘scarlet drop’ occurs then and the Catalogue notes the trope was inspired by David Belasco’s famous play, ‘The Girl of the Golden West’. The story is exciting and there are some notable scenes including a pose in a doorway and some very effective lighting.

A real treat was The Gardener / Trădgărdsmăstaren (1912), the debut film of Victor Sjöström. The original title The Cruelty of the World gives a better sense of the narrative. Once again star crossed lovers are separated by class differences. But the heroine suffers a rape as well. Years later she returns to the scene of her first love and that of the sexual assault. The film has all the power of the later Sjöström features but it encountered problems with the censors due to the subject matter. This was digital restorations from a print slightly shorter than the original release.

There were lots of other moving image pleasures in the week. Three early one dramas from Louis Feuillade. Features by Abel Gance, Le droit à la vie (1917) and Maurice Tourneur The White Heather (1919). a series of screenings of Max Fleischer KoKo animations: and a sizeable collection from The Chaplin Connection with examples of his earlier films like Shoulder Arms (1918): home movies: newsreels: Chaplin imitators and comedies influenced by Chaplin. And there were two programmes from the Belgium avant-garde film-makers. There were few notable canine performers this week but there was one of the classics in Keaton’s faithful collie who follows his master, on paws, out west.

There is more information on the Giornate webpages where one will look out in 2026 for the next Festival.