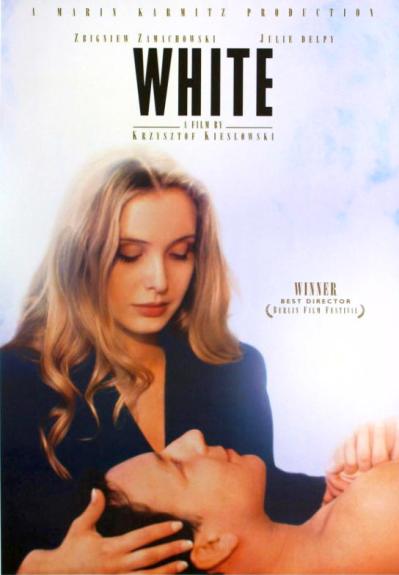

‘White‘ is the middle film of Krzysztof Kieślowski’s trilogy based around the idea of the tricolore and the revolutionary ideals of liberté, egalité et fraternité. ‘White‘ focuses on ‘equality’. It has tended to be the least celebrated of the three films, but there is no real reason why it should be and it is still highly rated. It stands out because, though it is a French production, the central figure is male and Polish and the narrative is mostly set in Poland. The cast still features a leading French actress but Julie Delpy doesn’t get the same screentime as Juliette Binoche and Irène Jacob in the other two films. Even so, Delpy’s character is at the centre of the hero’s thoughts throughout the narrative. As many scholars and critics have suggested, the film is also different as the Polish context is much more important in social/political terms in the narrative and, at a very basic level, the discourse about equality is most clearly rooted in the inequality between Poland and France, ‘East’ and ‘West’. Another difference might be that Kieślowski set out to make a comedy but then claimed that he had cut most of the comic elements. I think enough still remains to justify calling the film a ‘dark comedy’. Compared to the other two films, White is a relatively straightforward narrative which in the arthouse world is sometimes seen as simply ‘conventional’ but it does make the story more accessible to a wider audience.

Brief outline (no real spoilers)

Karol (Zbigniew Zamachowski) is outside the courts in Central Paris. He presents a despairing figure and is the recipient of a pigeon’s waste dropped from above. In the courtroom he attempts to fight against the divorce petition by his French wife Dominique (Julie Delpy). He doesn’t speak French and fails to convince the judge that there is anything that might prevent the divorce being granted. The divorce is based on the lack of consummation of the marriage. Karol and Dominique had a joyful physical relationship in the East, but something in his life in Paris has made Karol impotent. Despite a final attempt to get back with Dominique, a penniless and homeless Karol is reduced to busking and sleeping in a Metro station. He is spotted by an older Polish man who takes pity on him and eventually Karol does get back to Warsaw – but not without further humiliations. Karol is lucky because he finds his way back to his brother who has kept open their hairdressing business. The central section of the narrative finds Karol plotting his revenge on Dominique, although it isn’t clear if he still loves her – or if there is any chance she might re-consider. How does he ‘make good’ back in Poland? The answer is by simple buying and selling. After the end of the Cold War, Poland became a place where you could buy ‘everything’/’anything’, so anyone with intelligence and chutzpah could not only survive but prosper. I won’t spoil the end of the narrative for anyone who hasn’t seen the film. I’ll only say that it isn’t something that Dominique has been expecting.

Commentary

If White loses something in the trilogy because Julie Delpy is not on screen for most of the film, it gains so much more by presenting two excellent Polish screen actors, Zbigniew Zamachowski and Janusz Gajos (who plays Mikolaj, the man who rescues Karol) to international audiences. Both actors are well-known in Poland. Zamachowski was in the early years of a career in the early 1990s in which he has since clocked up over 140 credits while Gajos has had a distinguished career going back to the 1960s and working in television and theatre before becoming a teacher at Łódź National Film School. In White he offers a quiet and comic melancholy (if such a state is possible) in contrast to Zamachowski’s desperation and the two work well together. The film is indeed very Polish. It reminds me of the period in the UK in the early 2010s when we got see far more Polish films in UK cinemas, not just the occasional international arthouse film, but also the bigger commercial films. At that time the Polish-language speaking population in the UK numbered over 1 million and distribution of Polish films became viable. Sadly the tragedy of Brexit saw many Poles return home and we’ve lost that sense of being part of a wider Europe. In 1993 the ‘wider Europe’ was actually still eleven years away and it wasn’t until May 2004 when Poland became one of eight new and mainly Eastern European member states which joined the EU to make it a 20 nation group. I think you can recognise in this film that Kieślowski felt much more comfortable with his two lead actors than with some of French actors in the trilogy – both men had appeared in at least one of his earlier films. It’s a trivial point but I noted the increased importance of Polish drinking culture in White, especially in the sequence when Karol sets off to do business with an older traditional man and he stops off at a store to buy a bottle of ‘the most expensive vodka’. It reminded me of that quirk of English life when visitors arrive and the host gets out the ‘best biscuits’. Incidentally the same sequence with the expensive vodka also relates to, I think, the only mention of the Catholic Church in White. In the Polish films I remember, the Church is often as important as the vodka.

In each of the three films, there are moments when the lack of credibility in a scene works against the generally realist aesthetics. There are a couple of such moments in White, but I don’t think this matters – in fact they add to the ‘shaggy dog story’ feel. Some critics have described aspects of the story as farce. Also important is Zamachowski’s performance as the ‘little man’, underestimated by most other characters. Perhaps this is also a matter of ‘equality’ when Karol proves himself against the glamorous characters – the three French actresses perhaps?

If we really want to understand the film’s exploration of ‘equality’, we have to turn to the words of Kieślowski himself as they appear in the interviews he gave to Danusia Stok in 1993 (Kieślowski on Kieślowski, faber & faber) when he had finished shooting the film but before it was released. He explains first that Karol is a very sensitive man and in that sense he is like Julie in Blue and Valentine in Red. All his lead characters are people who have “some sort of intuition or sensibility, who have gut feelings” but none of this is spelled out in the dialogue. It has to be in the actors’ play and you have to feel it. The director argues that we all profess that we want to be equal but really we want to be more equal than others. Equality in White is understood as a contradiction. He then reveals that for Poles under Soviet-style communism there was a saying that “some are equal and some are more equal”. Karol is brought low and humiliated and he wants to bring himself up but then to go on and show he is actually higher than anyone else. Nobody ever said it would be easy to move from the domination of Russian pressure to the different kind of pressures of American-style capitalism. Kieślowski doesn’t say this but he is interested in its impact on Poles.

White differs from the other two films in technical terms only by having a different cinematographer in the form of Edward Klosinski. This does mean that there is less of a sense of the expressionist use of colour as seen in Blue. ‘White’ is used less symbolically apart from a couple of flashes of ‘white-out’ that might be orgasmic pleasure or passion. There are snow scenes in the Polish winter but nothing else to pick out. As well as the comments in the Stok book, I’ve also gone back to Sight and Sound June 1994 which includes an interview with Kieślowski, conducted by Tony Rayns which is well worth reading. It takes place in Hong Kong where Blue and White opened and closed the Hong Kong Festival. After this Kieślowski moved on to Tokyo where again the films were showing. The Rayns interview is well worth reading. There is a review in the same issue by Philip Strick, a critic I had plenty of time for. Here however he gives a very negative appraisal of White confirming to me that the film’s reputation has grown since the release of the whole trilogy. I’ll post on Red in a few days. I can’t find a trailer for White that doesn’t spoil the story for new viewers so I’ll leave it there, simply noting that I enjoyed White as much as both Blue and Red.If you want to watch the trilogy, it’s on MUBI in the UK and on many other streamers, generally through subscription but Apple have it for rent. There are also DVDs and Blu-rays.

I remember seeing the three, and much preferring White

LikeLike