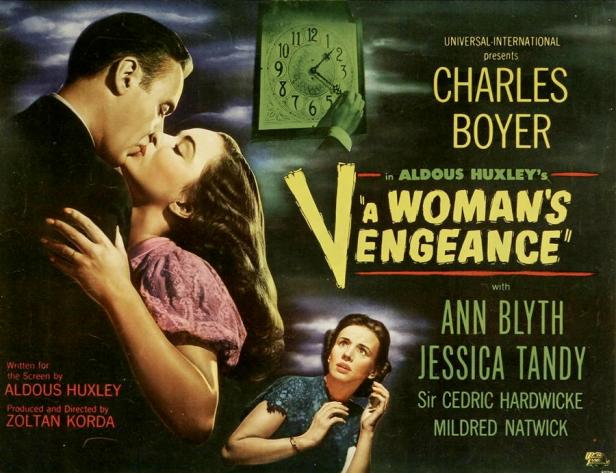

Here’s another ‘would be’ film noir from the Universal Blu-ray boxset Vol. 2 by Powerhouse/Indicator. It offers a fine example of a ‘Hollywood British’ crime melodrama with a nod towards Hitchcock, including several aspects reminiscent of Rebecca and his other 1940s films. It was scripted by Aldous Huxley, adapting his own short story ‘The Gioconda Smile’ which was also later made into a stage play. Producer-director Zoltan Korda guarantees the feel for Southern English country life and the leading players are Charles Boyer and Jessica Tandy with a strong supporting cast. Russell Metty is the cinematographer and Miklós Rózsa composed the score. Universal and Huxley appear to have changed the narrative, including the title, to give the film more appeal.

Charles Boyer plays Henry Maurier and his wife Emily is played by Rachel Kempson (a British stage actor married to Michael Redgrave and mother of Vanessa, Corin and Lynn). Maurier is a rather unlikely French-British businessman with a large country house somewhere in the Home Counties west of London and an interest in collecting art. Boyer was a big star with a history of major roles in both France and Hollywood but now he was slightly past his prime although still capable of playing a womanising husband faced with a wife in poor health. In the opening scenes he cannot help himself being charming towards his neighbour, a single woman in her mid thirties looking after her wheelchair-bound father, General Spence (Cecil Humphries, an English actor who died before the film was released). Jessica Tandy as Janet Spence was also a British actor, having already had a distinguished stage career in the West End and broken into British films in the 1930s before moving to Hollywood when her marriage to Jack Hawkins ended in 1940. Tandy would have known Rachel Kempson and Cecil Hardwicke, another leading British actor in Hollywood who played the Maurier family doctor. Leading the American acting contingent is Ann Blyth who had made such a success of her role in Mildred Pierce (US 1945) as Joan Crawford’s scheming daughter. She was at this point actually contracted at Universal and here she plays the latest of Maurier’s young women, perhaps younger than the others as she was only 19 when the film was released. But she is a much more naïve character in this case. Playing against type, at least the type she played for John Ford, is Mildred Natwick as Emily Maurier’s nurse. As Nurse Braddock, she is presented as suspicious of most men and Henry Maurier in particular.

This is a cast worthy of the more ambitious and slightly more expensive productions at Universal in this period. What we see is a plot that develops quite rapidly from the opening sequence which reveals a web of relationships primed for conflict. Maurier discovers that his brother-in-law Robert is in the house seeking money from his sister. He tears up the cheque and throws out Robert, thus making an enemy. Next Emily sends him next door to deliver a birthday present to Janet before he goes to the chemist to collect her prescription. Henry delivers the gift and discusses his new art purchase with Janet before returning to his car where we are perhaps surprised to see that the young Doris Mead (Ann Blyth) is waiting for him. In this sequence Korda has introduced several of the key players and also given us clues as to conflicts that might develop. In the next few scenes we will meet the other two key players – Mildred Natwick’s nurse and Cedric Hardwicke’s doctor. I’m not really spoiling the plot by revealing that Emily dies that night from something that triggers heart failure.

At first there appears to be nothing to suggest that Emily’s death is ‘suspicious’ – she was a sick woman. Henry is not actually there that evening but later he does seem to be rather hasty in deciding to marry Doris. Gradually suspicions will be raised and the second half of the narrative will eventually see Henry Maurier charged with her murder. But did he do it? Most of the audience will have seen the poster and perhaps watched the trailer, but the studio was careful in its presentation. The final sequence is extended. What will happen and how is the suspense maintained? By casting Charles Boyer, Korda (also the film’s producer) would be aware that the audience might remember that Boyer was the villain in the film Gaslight (1944) in which he attempted to drive Ingrid Bergman insane as part of his criminal plans. So perhaps they might be predisposed towards Henry as a potential murderer?

I think that the film is best described as a ‘gothic melodrama’ mixed with a murder mystery. I wouldn’t classify it as a noir, even though Russell Metty’s camerawork does enhance the mystery of the second half with low key lighting. It is packed with emotion but I’m not sure it feels like a romance. It isn’t alone in its mix of elements of course, there are several other films of the period – American, British, French etc. – that feature a similar mix. It’s not difficult to understand why Huxley would re-write it for a theatre production. All the performances are very good and the script supplies several clues as to how the narrative will develop. It’s the cinematic equivalent of the ‘well-made stage play’. It’s also a good example of how the mode of film noir camerawork seeps into the presentation of a wide range of genre films in the late 1940s. Of course, it can be argued that noir is a function of the mood of the period and that the visual style is also part of psychological horror. The final section also includes psychiatry. I should also mention Miklós Rózsa’s melodrama score and the art design/production design of Bernard Herzbrun and Eugène Lourié (known for his work with Jean Renoir). As in many of the Hollywood films of this period, there are three, possibly four, significant roles for women in this film compared to just two or three male roles. But, as Tara Judah points out in the booklet in the boxset, the three women are all presented from a misogynistic perspective (i.e. from that of Henry or Dr Libbard) – each shown in some way as ‘ill’. So, a film ‘of its time’, perhaps.

This is a much better film than I was expecting and I score it highly for the writing, performances and technical credits. I may have underestimated Zoltan Korda’s skill in making this kind of film which stands next to Cry, the Beloved Country (UK 1951) rather than his brother’s imperial fantasies such as The Four Feathers (1939). It also figures prominently in questions about Universal-International’s attempts to change its approach to production and to questions about genre and visual style in the period. The film is available on various streamers free as well as the Blu-ray disc reviewed here – which obviously affords the best presentation of Metty’s camerawork and the other technical credits. The disc also includes a useful presentation on the film and Huxley’s film career by Neil Sinyard.