Australian Cinema has had periods of both innovation and exploration, as well as periods of stagnation, since the first films were produced in the early 1900s. Currently there is a distinct development with the increase of films made by Indigenous filmmakers about the lives of Indigenous characters, both contemporary and historical. The Drover’s Wife by Leah Purcell is the latest example of an Indigenous film reflecting on colonial history in Australia. In doing so it takes us back to some of the earliest Australian films that have been compared to American ‘Westerns’. These were, in Australian terms, ‘bushranger films’ and the earliest of these was the Story of the Kelly Gang in 1906. Like the American West, Australia in the second half of the 19th century and on into 1920s was a difficult territory to police, even after the foundation of the Commonwealth of Australia in 1901.

Bushrangers were ‘outlaws’ and Australia also experienced ‘gold rushes’, cattle drives and conflicts between settlers and Indigenous peoples. In Australian films up to at least the 1970s (and arguably much later), Indigenous characters were usually portrayed either as ‘exotic’ figures in the landscape, poor communities in shanty towns, children in mission schools or trackers working for the police – familiar ‘social types’ in both American and Australian ‘Westerns’. In the last few years more radical films have appeared with Indigenous characters central to the narrative and a serious intent to explore colonial issues of racism and exclusion. Warwick Thornton’s Sweet Country (Australia 2017) is set in the late 1920s while Jennifer Kent’s The Nightingale (Australia 2018) is set in the 1820s in Tasmania. Both films got a limited UK release and Sweet Country has been shown on UK TV. The contemporary TV crime series Mystery Road initiated by Ivan Sen has some links to the historical narratives and has also been seen on UK TV. David Gulpilil, who died in 2021, was perhaps the major Indigenous star actor and he appeared in several films which explored aspects of of Australian history featuring significant Indigenous characters. The one most relevant to the discussion here would be The Tracker (Australia 2002), set, like Sweet Country in the 1920s and featuring Gulpilil as a tracker working for the police searching for an Indigenous man accused of murdering a white woman.

Leah Purcell is a proud Goa-Gungarri-Wakka Wakka Murri woman from Queensland. She is an internationally acclaimed playwright, screenwriter, director, novelist and actor and a cultural icon and activist, whose work stands at the forefront of the Black and Indigenous cultural renaissance and protest movement sweeping Australia and the world. Australian Financial Review named Purcell as one of Australia’s Top 10 culturally influential people because ‘she allows white audiences to see from an Aboriginal perspective’. (from Press Pack for The Drover’s Wife)

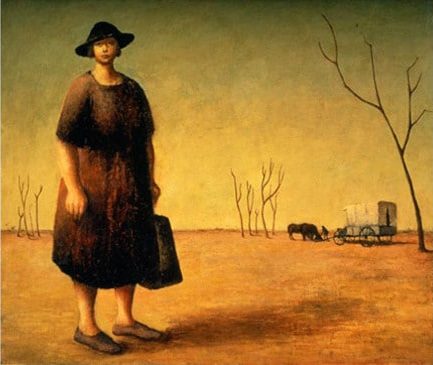

The Drover’s Wife was initially a short story by Henry Lawson, first published in a magazine in 1892. Lawson is one of the best-known Australian poets and fiction writers, especially in relation to ‘bush stories’. The story has been re-worked many times since and in 1945 a painting by Russell Drysdale was given the same title and appears to present the woman of the story depicted against the wild country (although the artist denied this). The short story offers only the initial scene in the film in which the woman and her children are threatened by a wild animal (a snake in the original story). The woman’s struggle in the story and the painting were long seen as representing the white settler’s attempt to survive in the harsh conditions of the ‘bush’. Leah Purcell extended the story in her stage play and now in her film offers a rich and complex narrative about a woman and her historical role viewed through the lens of Indigenous story-telling. The film follows what happens over the next few months to Molly Johnson and her children.

Purcell manages to include the racism and exclusion directed towards Indigenous people, the social class hierarchy of Victorian England, the nascent suffrage movement and the ‘stealing’ of Indigenous children. All of this is offered in the genre context of a Western with Mark Wareham’s photography of the Snowy Mountains and Salliana Seven Campbell’s very effective score. I think all the performances are good and especially Malachi Dower-Roberts as the young Danny Johnson.

The film’s narrative has a complex structure and also includes several ‘reveals’ that I don’t wish to spoil. It is necessary, however, to explain that Purcell uses devices such as flashbacks/flashforwards, ‘dream figures’ and occasions when edits seem to confuse the meaning of certain scenes. Her commitment to Indigenous storytelling may also create questions about the final sequence which acts as an epilogue. On a second viewing I noticed a number of metaphors including for instance the animal which threatens the family in the opening of the story. The snake has become a bullock, which for me symbolises the alien intrusion of a non-indigenous beast brought by settlers in order to fully exploit the land they have stolen.

This film has been described as an ‘Indigenous feminist Western’ and Purcell has created a secondary but parallel narrative about the young wife of the district’s new police sergeant. Both the sergeant and Louisa, his wife, are newly arrived from England. Louisa is a proto-feminist character, concerned about the widespread domestic abuse handed out by male settlers towards their wives. She’s determined to publish a women’s newsletter and to build a campaign. I don’t know whether this is historically accurate for the 1890s but it enables Purcell to set up the question of white feminism and whether it is possible for Louisa to ‘give a voice’ to Indigenous women. Molly Johnson has her own ‘voice’ and she intends it to be heard. Just as important, the extended story that Purcell puts onscreen also includes the issue of ‘stolen children’, the attempt by the authorities to take the children of mixed race families and to select those with least ‘Indigenous blood’ to be brought up as white children in foster homes (while ‘darker’ children are trained as servants). This practice is the central focus of Rabbit-Proof Fence (Australia 2002), set in the 1930s but only properly being discussed some sixty years later in the 1990s. The Drover’s Wife is certainly a narrative rich in questions and challenges for audiences, not just in Australia but everywhere experiencing exclusion an inequalities, i.e. most definitely the UK and US. But it’s also an exciting and engaging popular narrative. Its use of familiar conventions from Hollywood Westerns is effective and helps audiences outside Australia to begin to explore the colonial legacy of British settler culture.

The Drover’s Wife is a début film. It’s asking a lot to script, direct and star in your first feature but I think that Leah Purcell pulls it off with real passion and commitment. Initially released by Modern Films on just 37 prints in May, the film has slowly moved around the UK and Ireland. It appears to have a traditional release pattern and will be available to stream in August in the UK. Modern Films are also committed to supporting local independent venues through ‘various events’ so it’s worth checking out their website. The Drover’s Wife is definitely worth looking out for but do try and catch it in a cinema on the big screen if you can. In the US, The Drover’s Wife will be released by Samuel Goldwyn Films in August 2022.

I came to this after being impressed by Leah Purcell in High Country, which I enjoyed, but found slower and less gripping than the Mystery Road films and TV series. Apparently she was also in Jindabyne, but I saw that too long ago to remember. What a powerhouse performer and one-woman creative industry! She was even more impressive in this film, combining strength, stature and an appealing vulnerability in her voice. She’s also a terrific role model for older women, still woefully under-represented on screen.

I love a good revisionist western and liked her preoccupation with a character rediscovering / reconnecting with her indigenous roots and her ‘mob’. Obviously the dream storytelling and symbolism was central to that journey, but I think worked much better in the western genre with its mythic/legendary traditions than in the police procedural.

The stunning Australian Alps setting was a revelation, a real contrast to the dusty, desert settings of pretty much all the other Australian westerns I’ve seen – the ones you mention above, and others like The Proposition. The cinematography is breathtaking and delivers classic genre pleasures, like the marvellous scene of mother and son riding across the darkening mountains. The music is also very evocative, but maybe at times excessive eg the overwrought electric guitar in the violent fight scenes. The editing is a bit confusing too on occasion, and I struggled a bit with the story set up in the early scenes.

In fact, I found the quieter scenes between mother and son much more compelling and was hugely impressed by Malachi Dower-Roberts in that role. And intrigued throughout the film by the irony of Molly being driven by a compulsive desire to save her children, yet most of the time they were absent, hidden, or lost…possibly a metaphor for the stolen generation?

I very much agree with you that the film sets up the question of “whether it is possible for Louisa [the white proto-feminist] to ‘give a voice’ to Indigenous women. Molly Johnson has her own ‘voice’ and she intends it to be heard”. Initially, I felt the white feminist’s role and presence felt like a clunky, unnecessary addition to the story that’s powerful enough centering the self-sufficient Molly – ie a mistake. But then I realised it was probably deliberate, and at the end – if I remember correctly?-, we see Louisa and her ‘sisters’ from a high angle, which I read as an ironic comment on their smallness and wordy irrelevance to the silent legend that will be Molly.

LikeLike

I’m so glad you managed to see The Drover’s Wife. I’m completely with you on Leah Purcell. She is a one-woman creative and cultural industry indeed and I hope to find more of her work. I feel that High Country had a lower profile on BBC2 than The Jetty on BBC1, very clearly intended as narrative created by women. I started but did not complete a posting on that serial and would be interested to know what you thought. Have you watched Sambre on BBC4? I watched it over the first weekend and thought it was terrific. All the crimes are attacks on women but we see three different women attempt to find the perpetrator only to be let down by the system itself (with men in most positions of power).

LikeLike

Interesting- I started The Jetty but after 30 mins put it on a ‘view later’ shelf as it didn’t initially grip me. Will revisit, and check out Sambre.

Slightly at a tangent, but related to dramas dealing with male-female-racial dynamics, can I strongly recommend the Danish drama Prisoner (Huset), with Sofie Gråbøl? I love a good prison drama but this was far more nerve-shreddingly intense, grim, as well as authentic-looking and ‘political’ than any I’ve ever seen from the anglosphere – including Time – with incredible roles for the main female and ‘Muslim’ characters. On BBC iPlayer.

LikeLike