The city of Bologna was crowded for the 32nd edition of this archive Festival. The crowds, up to 3,000, swarmed in. So whilst there was a varied and exciting programme one had to exercise judicious judgement in selecting programmes as quite a few screenings were full, really full. As usual there was a mix of digital formats and 35mm. I think there were slightly less ‘reel’ prints than last year. But there were enough to satisfy a film buff starved of the ‘reel thing’ in Britain.

This year saw the partial inauguration of the Cinema Modernissimo, a vintage cinema under process of restoration. Every morning (repeated in the evening) the venue screened episodes from a US serial of the ‘teens, ‘Wolves of Kultur’. Produced by Pathé in fifteen episodes this was a spy drama with cliff-hanger after cliff-hanger:

our heroes, now a couple, are meeting dangers and escaping it, climbing, running, driving, on ships, motorcycles, trams, in woods, caves, lakes, on towers, peaks and rails. (Marianne Lewinsky in the Festival Catalogue).

In fact the episodes were rather reliant on intertitles for progressing the plot but there were some exciting sequences over the week. But it was the venue that was the star. Currently the auditorium is a dark cavern awaiting renovation. But this made it atmospheric. And the accompaniments by different musicians on different days, resonated around the impressive space. However, there is much work to be done and it seems unlikely that the Modernissimo will provide a new venue in 2019.

The star experience for 35mm film fans were the screening in the Piazzetta Pasolini from a 1930s Prevost Carbon-Arc projector. This year we had three, all devoted to the programme ‘Song of Naples, Tribute to Elvira Notari and Vittorio Martinelli’. Elvira Notari was a film director who, with her husband Nicola, produced films throughout the silent era that celebrated and dramatised the city of Naples. Vittorio Martinelli was a scholar and enthusiast for these filmmakers; he passed on ten years ago so it was also an anniversary. The atmosphere for these screenings in the Piazzetta was great. And all the films had musical accompaniments by Neapolitan singers and musicians. Worth a trip to Bologna on its own.

There were innumerable programmes covering early and silent film, classic mainstream cinema, documentary, art cinema and cinemas of liberation. The last included restorations by The Film Foundations World Cinema Project (Waquai Sanaway Al-dhamr, Algeria 1975), and a screening of Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino’s seminal ‘Third Cinema’ film La Hora de los Hornos Neocolonialismo y violencia (Argentina 1966 – 1968). There was a fine Argentinian film from 1939, Prisoners of the Earth / Prisioneres de la Tierra. Filmed partly in the Amazonian jungle the film dramatised the experience of bonded workers on fruit plantations. The plot was fairly melodramatic but the actual locations gave the film an immediacy whilst the critical treatment of the exploitation and oppression of native workers was powerfully subversive.

The key silent offerings were in ‘A Hundred Years Ago: 1918’ (Cento Anni Fa: 1918), and the majority of these were on 35mm. We had Charlie Chaplin’s Shoulder Arms and The Bond.; an early Germaine Dulac short, Âmes de fous, and a restored film with Italian Diva Pina Menichelli, La Moglie di Claudio (Cláudio’s wife). What I found most interesting were two films that featured the Soviet poet Vladimir Majakovskij. There was short both scripted by and featuring Majakovskij, Shackled by Film (Zakovannaja film’moj, 1918) which played with cinematic techniques and illusion. And there was a three reel feature The Young Lady and the Hooligan (Baryšnja I chuligan, 1918). The young lady of the title (Aleksandra Rebikova) is a newly arrived teacher at a rural school. Majakovskij, who also scripted the film and was also involved in other aspects of the production] plays the hooligan, though this term does not really describe the character. The Italian translation had him as a ‘punk’. He seems unemployed and is an outsider among the locals. He is set upon by some of the pupils and their fathers. The film is fairly melodramatic and our protagonist is smitten with the teacher. But the film is also experimental with a dream sequence and scenes with multi-imagery, showing the influence of Futurism.

We had a programme of later films from the same territory, ‘Second Utopia: 1934 – The Golden Age of Soviet Sound Film’. As in China and Japan the new sound technology arrived in the Soviet Union later than in the Western capitalist countries. It also coincided with the change from a cinema predominately concerned with the political values of revolution and socialist construction to a more conventional approach:

‘Entertainment’ stopped being a curse word, and audiences returned to cinemas.(Festival Catalogue).

This is somewhat of an exaggeration. If you watch the films of Boris Barnet it is clear that audiences of the 1920s were offered both political dramas and documentaries but also dramas that were extremely entertaining titles. The advent of ‘Soviet Socialist realism’ tended to reduce the politics to slogans and offered a more one-dimensional view of Soviet Society. Chapaev / Čapaev was constructed around the heroic protagonist of the title. He is a military commander in the Civil War, when Britain, France, Japan, the USA and allies invaded the young socialist state. Chapaev leads regular and irregular forces against the invading Czechoslovakian Legion, mainly around the Trans-Siberian railway. In leading the battles against the invaders Chapaev has to come to terms with the Political Commissar. This resolves the drama and Chapaev emerges as a heroic figure but with little sense of the contemporary contradictions.

A different approach, less in line with ‘socialist realism’ was The Youth of Maxim (Junost’ Maksima), set in the Tsarist period around 1910 and written and directed by Grigori Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg. This film retained the vitality and some of the experimentalism of their silent work with FEKS. The sound sequences are fairly stagy but the action sequences of demonstrations, conflict and revolutionary underground work are impressive. There are some fine examples of moving camera, exteriors with a strongly expressionist look and factory settings worthy of a silent film. And whilst Maxim is heroic this is only after a tutelage by an experienced Bolshevik and involvement in class actions.

Hollywood conventions were on show in ‘William Fox Presents: Rediscoveries from the Fox Film Corporation’. There was a screening of 7th Heaven (1927) in the Piazza Maggiore with a full orchestral accompaniment. And among the other titles was delightful comedy, Bachelor’s Affairs (1932) in which Adolphe Menjou as middle-aged playboy Andrew Hoyt discovers the drawbacks of marrying a young, beautiful blonde, Eva Mills (Joan Marsh). The film subverts Menjou’s standard persona whilst providing quick and punchy dialogue.

Alongside this was ‘Immortal Imitations: The Cinema of John M. Stahl’. Stahl started out as an actor then moved to direction in 1914 and continued until 1949. He directed 43 films, many of them are lost. His films are predominately melodramas, often adapted from best-selling novels. The programme in Bologna will be paralleled at Le Giornate del Cinema Muto in October when there will be presentation of most of his surviving silent films. Stahl’s best films dramatise romantic relationships, often where a woman is forced into a ‘back street’ in a relationship with a married man. When Tomorrow Comes (1939) is taken from a story by James M. Cain. Irene Dunne plays the waitress Helen Lawrence who has a brief affair with pianist Philip Chagall (Charles Boyer). The principal leads are excellent and the melodramatic plot develops the strong emotions. The intriguing opening presents a waitress strike in New York but this soon fall away as the romance takes over.

A woman kept in the ‘shadows’ in a different sense is the central line in Imitation of Life (1934), adapted from the novel by Fannie Hurst. We have two single mothers with young daughters, Beatrice Pullman (Claudette Colbert) and Delilah Johnson (Louise Beavers). Beatrice is white, educated and self-reliant; Delilah is black and dominated by years of submissiveness. The film not only dramatises the inequities of racist classification and representation but also contains an undeveloped critique of US capitalism. Beatrice acquires wealth and fortune by marketing Delilah’s home-made pancake recipe. Yet even when the pair move to a affluent mansion Delilah remains ‘downstairs’. This contradiction finds potent expression in the situation of Delilah’s daughter Peola (Fredi Washington) who can ‘pass for white’. The film lacks the trenchant criticism in the treatments of this subject by Oscar Micheaux (for the segregated ‘race cinema’); but, I think, is superior to the better known remake of 1959.

‘The Rebirth of Chinese Cinema (1941)’ offered films from the period when, following the end of the Japanese occupation, the Communist Party of China defeated the capitalist Kuomintang and embarked on its own Socialist Road. The nine titles included straightforward entertainment films, films of resistance during the occupation and films made under the new dispensation.

Along the Sugari River / Songhua Jiang Shang (1947) was produced in Manchuria. Officially in a studio under the control of Kuomintang the film drama tends more to the political line and struggle of the CPC. The film opens on a rural family prior to the Japanese invasion. When the Japanese army arrives their treatment of the indigenous people is brutal and racist. Members of the family succumb to the Japanese violence and finally a young couple flee the village on Sugari river and the husband takes work in a Japanese run mine. After a disaster the Japanese offer derisory compensation to victims. A protest is brutally put down with many deaths. The young couple flee again and are rescued by partisans; thus they join the struggle against the occupation. The film used an amount of location work and prior to the occupation sequences have lyrical feel. The maltreatment under the Japanese is well presented and there are some fine tracking sequences. Like the other titles this film had been transferred to DCP. The surviving 35mm prints were rescued by a French University Department, thus they have Chinese dialogue with French sub-titles. Apparently the prints had not been looked after for years so there survival is welcome.

Equally rare we enjoyed a retrospective of some films by Yilmaz Güney, ‘Despair of Hope’. The Catalogue notes opened with a quotation from ‘The Last Temptation of Christ’, by Nikos Kazantzakis:

Hope, lasting too long, had begun to turn into despair.

which suggests a meaning for the title.

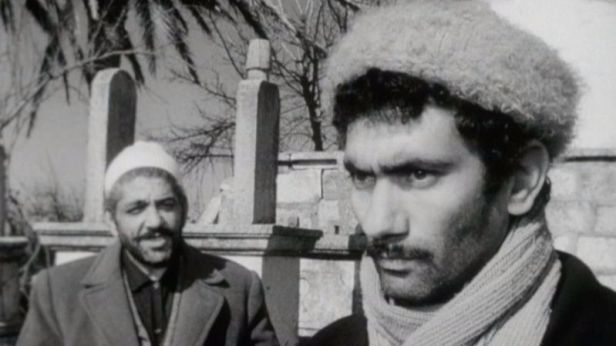

Güney was a major star of Turkish cinema in the 1950s and 1960s and went onto become a major film-maker. But his political views, expressed both in writings and in his films led to prosecutions, prison and eventually exile. He both wrote and directed films, and later, when in prison or exile, he supervised his films through collaborators. There were three titles screened plus German documentary. The Legend of the Ugly King / Die Legendae vom Hässlichen König (2017); a title that picked up on Güney’s nickname in as a star noted as a

tough-guy character [who] was often forced to violence because of certain social circumstances . . .

This could be seen in Bride of the Earth / Seyyit Han (1968), a film in black and white widescreen, clearly influenced by the ‘spaghetti westerns’. Güney plays Seyyit, a loner who has been in exile from his village. He returns just as his love Keje (Nabahat Cehre) is being married off to a local landowner. Here we see the power relations in traditional rural society. Seyyit finally has to confront Haydar and his henchman, whilst Keje becomes a victim of the conflict. Just as in a western Seyyit rides away alone a the end. This is a bleak action film, but also one that offers a critique of the traditional power structure in rural Turkey,

The three titles had been transferred to DCPs for the Festival. The quality was reasonable but not great on contrast or definition in long shots. This was presumably partly due to the quality of the surviving 35mm prints.

There was a tribute to the great Italian actor, ‘Marcello Come Here. Mastroianni Rediscovered (1954 – 1974)’. The programme included a fine comedy directed by Alessandro Blasetti, La Fortuna di Essere Donna / Lucky to be a Woman (1955) with Mastroianni as a photo-journalist playing opposite a Sophia Loren as a perspective subject/model. Both actors were delightfully witty.

And there were the programmes one could not fit in like a number of vintage colour prints and an array of documentary films. A festival jury selected the DVD Awards, including Flicker Alley’s The House of Mystery / La maison du mystère (France 1921 – 1923) for ‘The Pater Von Bagh Award’ There was also the announcement that the sadly missed Peter Von Bagh [Festival Director] has been replaced with a ‘gang of four’; Cecilia Cenciarelli, Mariann Lewinsky, Ehsan Khoshbakht and Gian Luca Farinelli. All are experienced in the Festival and wider cinematic culture. It will be interesting to see how they address the increasing popularity of the Festival whilst contemporary cinema is changing so rapidly.