Linklater’s latest film appears to be acting as a lightning rod for critical reaction to his work. There is a great deal of review and commentary, a sudden rediscovery of Linklater as auteur, as he was first embraced when he brought out Slacker during the indie explosion at the end of the 1980s into the early 1990s. Linklater, I think, has suffered from his ability to match form to the material. He has talked about envying the kind of career Vincente Minnelli could have in the Hollywood studio system, directing a wide variety of material on call. For Linklater, this ability has meant that he has been underrated – both in his treatment of form and content. Perhaps a willingness just to direct – such as Bad News Bears – might reduce his value in the eyes of some. How useful is it to think of him as an auteur, now the term has resurfaced.

The obvious – and great – achievement of Boyhood is how it maintains one consistent tone in the visual appearance of the film, in the performances in filming (shooting on film and not digital) over 12 years. There’s a nice scene, as part of Gabe Klinger’s totally engaging documentary portrait: Double Play: James Benning and Richard Linklater (2014) where Linklater shows Benning some of the work-in-progress on Boyhood. Sandra Adair, his long-time collaborator as editor, talks about how their relationship was formed. (Long-time collaboration is a characteristic of auteurs – and Linklater). Slacker – his defining feature (his second feature film) – demonstrates not only the crafting of a complex narrative structure, but Linklater’s passion for a community of literary, philosophical and artistic engagement and his strong roots in Austin, Texas. These traits have been constantly apparent through films from Slacker, through Waking Life (2001) and up to Bernie (2011). This latter film failed to gain commercial distribution (emphasising how increasingly difficult it is to release independent work, even when you have the kind of name and track-record Linklater does). It represents the parts of East Texas, Linklater’s home turf, with humour, with sympathy and with a writer’s eye for a great story, however uncomfortable the revelations or strong the local feelings about them. (Bernie is after all, a tale of the convicted murderer of an elderly lady and still continues to generate controversy – not least following Bernie Tiede’s release on the basis he lives at Linklater’s property).

Art and life intertwine in the above. Linklater’s work is generally all about connections – in the structure of his films, in the empathic way he draws people so that we recognise their feelings and relate to them strong. However, there is a detached intellect drawing these connections and making them work successfully as narratives in the cinema which avoids sentimentality. This makes me question the parallels made in reviews with documentary, and highlights a crucial difference between what a documentarian is attempting to do compared with a fiction film writer. Linklater is art not life – a storyteller rather than an observer. What is most visible in Boyhood is the European influences Linklater draws on – and how he develops them in a parallel narrative structure. Mason Junior reminds us of Antoine Doinel in Truffaut’s (self)exploration in Les quatres cents coups, not in control of his own fate and acted upon by the adults in his life. Linklater, though, likes to construct a narrative out of the different threads and see how they throw up comparisons and contrasts as it unfolds. He signals this connectivity – and this construction – through metaphors running through, visually, in the frame. Patricia Arquette’s single mother raises the two children working hard, limited by her circumstances whilst Ethan Hawke as the father works and travels away on a whaling ship. The nearest she comes is the whale on the side of the removal van and the artwork on her children’s walls. Strong symbolism to emphasise the difference in circumstances. One of the greatest strengths of Linklater’s episodic design is how the threads of both adult and children’s lives intertwine and we shift perspective constantly to walk a mile in each of their shoes. It’s filmmaking of great control and detail which appears to unfold as naturally as documentary observation.

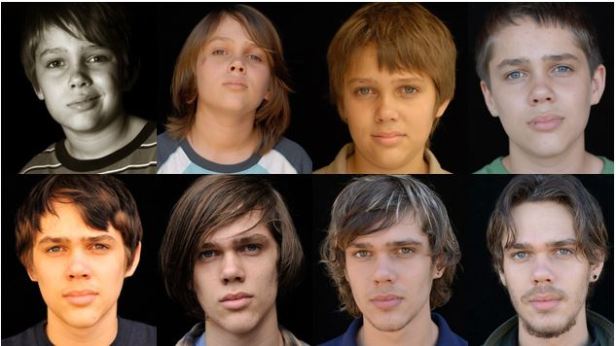

As part of a showing at Bradford with its hard-core of dedicated cinéphiles, a member made an interesting observation about those directors who have place associated with them and mentioned another native of Austin, Texas: Terrence Malick. It’s an interesting comparison – how each of these filmmakers use their understanding of space (and their place) in a different way. There are the parallels between something like Boyhood and Malick’s Tree of Life, both epic in their treatment because they explore the idea of growing up and maturity (and what those things mean). Tree of Life tested audience’s staying power because Malick introduces his modes of reflection by moving out of the diegetic, narrative space. Linklater, as evident throughout the Before trilogy, is ‘the auteur’ of staying in the moment with his characters. This might be one reason that many of the reviews focus so heavily on the documentary models, ignoring how highly-wrought his work is. It’s curious to see the parallels with Seven Up, the Michael Apted-directed British series that has followed a number of children through their lives. Their stories have a resonance for all of us. Linklater’s purpose, though, is much more like Malick’s than Apted’s. He wants to explore what boyhood means, how the kind of childhood we have affects the kind of adults we might become. And, as sprawling nineteenth century novels did, weave in philosophical and intellectual reflection around our emotional engagement with the characters. The casting becomes a narrative device and productive in itself. We watch in parallel as Ellar Coltrane (and Linklater’s own daughter Lorelei Linklater) grow up through the production of the film – whilst we are strongly rooted in the present tense in each episode. Just as we watched Hawke and Julie Delpy talk, argue discuss and fall in love in the long takes of the Before trilogy but grow up/grow older across the trilogy. Linklater is fascinated with all these aspects – reviews that seem to centre him as an auteur of ‘boyhood’ seem reductive. Perhaps his own boyish face is to blame for this review ‘chatter.’ (As an aside, how fortunate that he chose the kinds of actors who can/are prepared to age on screen. The close-up on the smooth, modern star’s face is eliminating that very thing that makes Linklater’s films so fascinating – being able to empathise with the characters and see ourselves reflected in their faces).

Boyhood, therefore, was the ‘indie epic’ – to use Linklater’s own description. As another of our Bradford group commented, he is in control of structuring emotion – of creating scenes of our lives which convey emotion acutely. His work creates a real sense of connection and connectivity. He’s the guy who made School of Rock after all. Boyishness aside – Linklater’s body of work is a masterclass in narrative filmmaking.

Sight and Sound July 2014 – carries an interesting inteview with Linklater as part of their feature: http://www.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/sight-sound-magazine/reviews-recommendations/film-week-boyhood

My feeling that this film (which I did like very much ) ought to be titled ‘Childhood ‘, for it is as much about girlhood as boyhood, encapsulated in the growing up of the sister played by Lorelei Linklater, I do agree that drawing parallels with documentary ‘longitudinal’ studies of life are rather misplaced.

LikeLike

I think Rona is right about the status of this film and about Linklater’s distinctive traits as a filmmaker. But in the end I wondered what the aims of this film actually achieved. It is certainly as much about parenting as adolescence. And I felt that the early parts of the film had a freshness which gradually dissipates as the chronicle progresses. Moreover, the early part of the film appears to have a satirical and political strand that also evaporates as the film progresses. And the final sequences of the film, as boyhood ends, made me squirm. But then I thought that Malik’s Tree of Life was grossly overrated.

The cast are good, especially the adult: and the production values are good: the script sounds overly familiar.

LikeLike

I agree there’s an eclecticism – and I find myself mapping the film onto Linklater’s filmography, considering where each episode sits against the work he was doing elsewhere. I see what you mean about the politics – and ‘Fast Food Nation’ is a film where, although characters drop out of the narrative unexpectedly, the political theme stays strong throughout. But I enjoy Linklater’s even-handedness in this, such as with the bible-belt characters (which again seems to map onto ‘Bernie’ and those East Texas attitudes). I don’t think the script is so overly-familiar because of Linklater’s approach to time in filming – the concentration on remaining in the moment with the characters (and leaving aside a more forceful narrative arc).

LikeLike