One of the most garlanded films from East Asia in 2011 has finally made it into UK distribution – and it immediately goes into my Top 10 of 2012 releases. A ‘simple tale’ this may be, but it is exquisitely made and packs a mighty punch both in the emotions it arouses and the subtle commentary it makes on contemporary Hong Kong society – and on the power of nostalgia. It’s a star-laden production from the leads to the cameo appearances and the creative talent behind the camera. Ann Hui is the doyenne of HK directors, Andy Lau is the superstar of Chinese cinema and Deanie Ip, a significant figure herself in the 1980s, has come out of retirement to win the acting prizes. The film looks terrific thanks to Yu Lik-wai (best known for his work with Jia Zhangke) and the minimal piano score by Law Wing-fai is perfect.

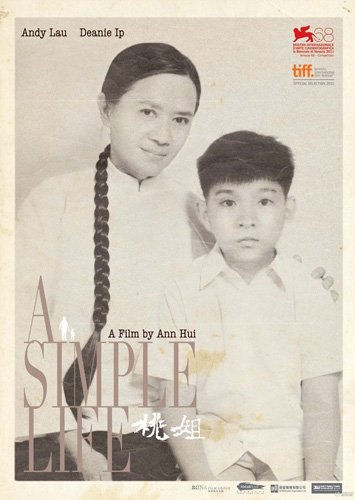

A Simple Life is in some ways a nostalgic film – or at least a film about how memories inform the last few months of a powerful relationship in a middle-class Hong Kong family. I recommend the film’s quite beautiful website with its explanation of the role of the amah in Hong Kong households. I’ve deliberately chosen the nostalgic poster above to illustrate this.

I take the amah to be a colonial legacy (similar to the ayah in India). The amah was a maid cum nanny, often recruited as a young teenager, who would pledge herself to a family in which she would gradually assume charge of the children as and when they were born. She wore a uniform of black pants and a white blouse. Under British colonialism, the amah would serve in both the coloniser’s homes and those of the local middle-classes. The bond between amah and child would be very strong and would carry through to adulthood. A Simple Life is based on the real world experience of producer Roger Lee. In Susan Chan’s script Deanie Ip plays Ah Tao, the amah of Roger (Andy Lau), the last remaining Hong-Kong based member of a family in which his mother and siblings (now with children and later in the narrative, even grandchildren of their own) have migrated to California. Ah Tao has been ‘in post’ since she was a young teenager – over 60 years. Roger is an accountant in the film industry, often away on business. One day, on his return from Beijing, he discovers that Ah Tao, now his housekeeper, has had a stroke. He decides to acquiesce to her wish to retire and live in a care home and when she leaves hospital, he takes her to one that he has found, owned by an old and rather disreputable friend (played by the Hong Kong actor-director Anthony Wong).

Roger finds himself maintaining his close relationship, visiting Ah Tao and taking her out. Her decline is gradual but inexorable but in the process she develops relationships with several of the other residents in the home. The home itself isn’t too bad and it is in the local area that she knows and wants to remain in. Ann Hui chose the district herself as a location for the shoot. It is quieter than the more bustling streets well-known to film lovers. Hui was one of the pioneers of a form of social film with a realist aesthetic during the period of the Hong Kong New Wave in the early 1980s and A Simple Life feels very ‘located’. The film offers us a commentary on the realities of social welfare in Hong Kong and on the new system of ‘service’. Roger remains impassive when the charges for ‘escorts’ (the carers who take the residents out for hospital trips etc.) clearly delineate the Filipinos, Mainlanders and ‘Foreigners’ etc. (I confess that I didn’t grasp all the details but the sociology is interesting). This is confirmed when we see the interviews for a new ‘maid’ to help out in Roger’s flat – the candidates are clearly not prepared to consider the kind of work the amah did. Status is important in Hong Kong and some of the funniest moments come when Roger, because of his casual clothes, is mistaken first as an air-conditioning maintenance man and then as a taxi-driver. In the home, Roger describes himself as Ah Tao’s godson. There is a whole discourse about service and social class bubbling beneath the surface of the exchanges in the home. The older residents probably recognise the real relationship but the younger staff and visitors take it at face value.

The irony is that I’ve read that Andy Lau really is Deanie Ip’s godson (although she is only 14 years his senior). This and other relationships on the set infuse the film. Many of the actors and crew have worked together before dozens of times going back to Ann Hui’s earliest work. The directors Tsui Hark and Sammo Hung play versions of themselves. In an interview, Hui points out that most of the female leads in the film have won a Best Actress award. The film seems as much about validating and celebrating the history of Hong Kong cinema as it is about the amah system.

In the end, however, this is a family melodrama and when the whole family celebrate the first birthday of Roger’s great-nephew (a child who is now American-Chinese-Korean), I was forcibly reminded of scenes in Edward Yang’s Yi-Yi (A One and a Two, Taiwan 2000) and the stories of extended families coming together. A Simple Life uses both the Chinese New Year and the Mid-Autumn Festival (Moon Festival) as foci for the presence/absence of family and the importance of social interaction. Although the film is, I think, technically a melodrama, it is marked by the absence rather than the ‘excess’ of expressionism in music or mise en scène. Everything seems restrained and low-key – meticulous rather than colourless though. If there is excess it is in the detailed focus on rituals like cooking and eating. The emotional attachment between Roger and Ah Tao is expressed through the food they make for each other – and how they talk about it. Chinese culture surely revolves around the pot! When we discussed the film after the screening I think one of the most interesting aspects of the film was the way in which Roger handled the inevitable death of his amah. How he behaved seemed to demonstrate a real difference between Anglo-Saxon and Chinese attitudes towards a ‘death in the family’. His actions seem far less sentimental than actions in a similar Western film – but they don’t detract from what we know is his deep emotional attachment to his amah. On the other hand, Deanie Ip says that she thinks Roger could have done more for his ‘Tao Jie’ and she feels it was a very difficult role for Andy Lau. I must see the whole film again, but especially the last third. I realise that there are large chunks of back story that are not explored – unless I missed a cue. Has Roger ever had a wife or a lover? How important was the heart surgery he had some time earlier? In many ways Roger seems like as much of an anachronism as Ah Tao in his flat with few of the accoutrements of modern living.

I’ve seen reviews of this film in the Western press which refer to its long running time (118 mins) and dismiss it as a ‘crowdpleaser’ for older audiences – i.e. not the kind of film to interest ‘real’ cinephiles. I couldn’t disagree more. It’s a wonderful film that will reward attentive audiences.

Here’s a trailer):

. . . and an interesting blog from Singapore remembering the amah in that culture.

I thought about the idea of melodrama after seeing this film – drama with music. I thought it was an essential description for this film but it created problems (as you comment) using it compared to the western forms (or Hollywood forms) that audiences in the West may be used to. I noticed how the Sight and Sound (UK magazine) review suggested the music was intrusive. But, compared to typical western melodramas, it was surprisingly restrained alongside the performances and the camera style. I think this mingles with the way in which we don’t know the backstory of Roger (Lau) or Ah Tao (Ip) – it’s alluded to in a very realistic way during family conversations, just as it would be amongst people who are very familiar with it in any family. This was part of the way in which it has a great emotional power and universality even whilst it was clearly culturally situated. The situation of the care home is shared across certain countries and certainly has familiarity in the UK. The scenes shot in the care home on the first evening of her arrival (and the first day) were so well-observed cinematically – using camera work that focussed on the small details that were unacceptable or unfamiliar from Ah Tao’s perspective. In the audience, we might mentally cry out that’s horrible and look for her to be somehow rescued – but the deft power of the film was subtly to demonstrate how anyone adapts into an environment – to its benefits and minuses.

The film sketches out a number of characters very effectively – and seemed (on first viewing) to move between sequences as if from a documentary (the inhabitants sitting in the entrance – day after day – at the care home) and more heightened visual style. It emphasises how we inhabit a world of greater sensations in periods of change (a kind of yellow filter on the shots at times?) and blended in character perspective shots occasionally to give us some reflection of their thoughts against their verbal restraint. The acting was peerless to match the subtle direction – a moment when Lau stands just that bit too long at a street bin spoke emotional volumes.

This style of filming prevented an overlaying of too much emotion (through overstated visual or sound hints) so that it beautifully expressed the idea that love is expressed in a number of ways, not always (in fact rarely) in direct interaction. It still worked to produce a melodrama’s effect on its audience – a proper “weepie” – and that’s truly a compliment.

LikeLike