Thamp is a Parallel Cinema film from Kerala, directed by Govindan Aravindan. The film has been the subject of a 4K restoration for the Film Heritage Foundation in India with Prasad Corporation Pvt, the World Film Foundation and Cineteca di Bologna. A collection of reviews and resources are available on the film’s page of the Film Heritage website. Thamp is part of the New Cinema/Parallel Cinema of the 1970s, opposed to the popular entertainment cinema of Kerala and seen as a form of art cinema. Various reviews of the film suggest that its approach is similar to ciné-vérité. I’m never quite sure what exactly is meant by ciné vérité. My understanding of it as practised by Jean Rouch suggests a filmmaker provoking a reaction in people s/he films. I feel the strongest influence on Indian filmmakers was probably Italian neo-realism or other forms derived from it. Aravindan was a successful cartoonist with a long running and partly satirical strip and also interested in music. He produced, wrote and directed this film which has a very simple starting premise. A travelling circus arrives in the village of Thirunavaya on the banks of the Bharathapuzha river in North-Central Kerala and sets up its circus tent on a large sandbar close to the village. Aravindan claimed there was no script as such and he simply filmed what happened. There are a few actors among the circus personnel but most people we see are non-professionals.

The first section of the narrative sees the truck arrive with seemingly the entire circus – people, animals, tent and props – carefully packed on the vehicle. The camera appears to flow around the activity in the hands of cinematographer Shaji Neelakantan Karun. It pulls back to observe the tentpoles going up in a very long shot – both beautiful and informative. The two shows a day are advertised with leaflets and posters and the villagers flock to see the show. It’s India so bureaucracy must be appeased. The circus has applied for permits in advance. All is well and the local head man is invited to preside over the first night introductions. He demurs and suggests a local bigwig who has just returned from Malaysia. Here is Kerala in a (coco)nutshell. It’s a well-run state with high levels of literacy and its wealth is partly a result of so many of its citizens travelling abroad to work.

The visual style of the film is neo-realist but the narrative is not driven by the demands of a melodrama such as in the classic Italian neo-realist films of the 1940s. Instead, Aravindan appears to be most interested in the various issues important to the circus performers and support staff and also the response of the villagers to the presence of the circus and the different acts in the show. As well as the acts themselves, the camera also picks out faces in the audience, both the children and the adults, eyes wide with amazement or laughing and smiling or sometimes just caught in moments of rapt attention. There is also a clear social commentary at play in which the camera observes the rich man, the circus manager, the clown and some of the other performers.

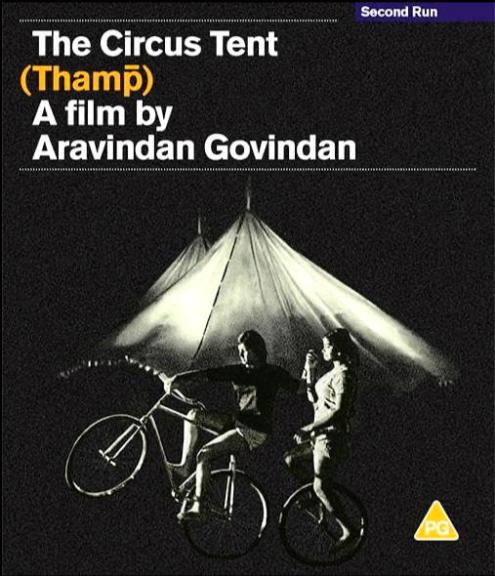

I watched the film on a rented Blu-ray disc of the restoration from Second Run released in 2023. The disc has two extras. One is a short piece to camera by Aravindan’s son Ramu giving some background on his father’s life as a cartoonist and a member of informal groups of artists in Kerala. The other is an interview with Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, director of the Film Heritage Foundation and Jalaja one of the young actors in the film enjoying the red carpet at Cannes in 2022. The interview is conducted by writer and broadcaster Anupama Chopra. Dungarpur suggests that some of the influences on Aravindan included Robert Bresson and Luis Bunuel and he says that Aravindan was very interested in Bunuel and he notes the irony in that the restored print was shown in the Bunuel Cinema in Cannes.

As the film progresses we recognise that some characters are picked out as well as certain routines such as the rehearsals by the girls who perform stunts on bicycles or on the high wire or trapeze. There are also interesting edits that offer comparisons of the differences in social class and wealth. A sequence which shows two circus performers, the strong man and his companion of short stature visit a ‘grogshop’ to drink arak is contrasted with later scenes of drinking among the élite and a more formal celebration for the circus staff led by the manager. One of the few clear narrative strands woven through the film involves a young man who may be the son of the wealthy man back from Malaysia. We see the young man outside beneath a large tree trying to learn about the drumming of one of the local festival drummers while inside his sister (?) listens to a modern LP in the upper middle-class home. The young man is part of another contrast at the end of the film. We hear one of the older performers (actually she addresses the camera) telling us she is tired: she has been ‘on the road’ with the circus since she was six years old – fifty years in total. At the end of the film the young man stops the truck when the circus is leaving town and asks if he can ride with them.

The circus draws audiences for a few days but then the excitement of the villagers turns to a local religious festival which Aravindan covers with the same observational camera, picking out the male dancers – dancing displays are an integral part of traditional culture in the region. The film is a treasure trove of singing, dancing and circus performances. Overall the technical accomplishments of Aravindan and his creative collaborators are astounding and this restoration presents them very effectively. Critics have picked out the ability of cinematographer Shaji Neelakantan Karun to capture the faces of the villagers and the circus troupe in wonderful close-ups which balance the long shots. I was also impressed by the subtle inserts of brief scenes that speak about the unique nature of Kerala as a state. For instance, a short sequence in which the rich man of the village returns to his mansion after inspecting preparations for some form of rally, is suddenly transformed into a political statement when a group of villagers surround the car canting “Long live the revolution!”. Kerala has one of the few governments in which two communist parties are often the largest parties in the state assembly. In 2024 it is one Indian state where Modi and BJP are unlikely to get much support. The ending of the film is actually rich in different moments. I realised that I had misses the development of a possible romance and the young middle class man is shown contemplating his life while on the soundtrack popular Western music is heard. Some reviewers argue the film is too long and too slow but I found myself going back and rewatching many parts of a film text that is so rich in representing the culture of what is for me the most fascinating state in India.