When this film was released in the UK early in 2024 it came wreathed in acclaim from many festivals and awards ceremonies but I decided not to go and see it. I was urged to see it by several friends but still decided not to. I can’t be certain why this was but partly I think I felt that I couldn’t face another Holocaust film but also that I have a general aversion to films which are suddenly talked about by everybody. On the other hand I’ve been impressed by two of director Jonathan Glazer’s earlier films. I finally decided to watch it (having avoided reading anything substantial about it) for two reasons. First, it is currently showing on All 4 after a recent broadcast on Channel 4 and second because I listened to a 30 minute ‘Illuminate’ documentary on BBC Radio 4 which explored the work of a woman who recorded interviews about the dreams of Germans in the 1930s living under the Nazis. I found this an intriguing account and wondered if it would have anything to do with Glazer’s film. I don’t think it does directly but like the film it aims to raise different questions about how people experienced and discussed life in the Third Reich. Both projects focus on people rather than events.

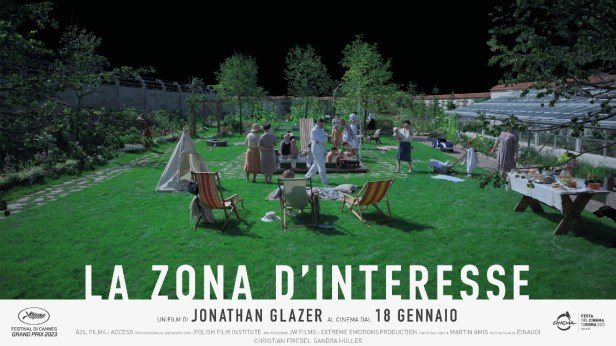

‘Zone of Interest’, the Nazi bureaucratic term for the environs of Auschwitz, was also the title of the Martin Amis novel from 2014 which Glazer optioned at the time. I haven’t read the novel and to be truthful I never liked the work of the younger Amis. Fortunately Glazer’s eventual approach to the book changed it significantly. The narrative now simply explores the daily routines of the real family of the Auschwitz Commandant Rudolf Höss and his wife Hedwig. There are five Hoss children ranging from a baby to a teenager, two boys and three girls. Their house and well-featured garden are just outside the walls of the extermination camp and Glazer used the actual location but also a set of the interior of the house. There is very little narrative structure until the latter half of the film when Rudolf is promoted to deputy inspector of camps and assigned to Berlin. The film ends just before he is sent to Hungary to oversee the transport of Hungarian Jews to the camps. All other events are simply short episodes involving Rudolf, Hedwig and the children plus their servants and visitors. As one reviewer puts it, it is more like an art installation than a narrative film.

I was a little surprised to discover some of the negative reactions to the film. Manhola Dargis in The New York Times describes it as a “hollow, self-aggrandizing art-film exercise” and Nicolas Rapold in a BFI Cannes report suggests “it notably avoids techniques that might foster an emotional identification with the family dynamics and actually shake up an audience”. Against this are arguments that only an art film could deal with the material and another that actually the film is likely to stay with viewers who have clearly been affected emotionally (Wendy Ide in the Observer). I’m not quite sure what I make of it. Glazer allows the material to speak for itself, simply observing actions and reactions with generally wide shots by Lukasz Zal, the cinematographer perhaps best known for his work on Pawel Pwlikowski’s films. The time period is from Summer into Winter and Hedwig is obsessed with her garden while Rudolf rides his horse and entertains the industrialists who build the gas chambers and the furnaces. Several commentators describe the family life as banal (a reference to Hannah Arendt’s later remarks about the banality of evil?) but others comment on the ‘model family’ growing up with the ‘National Socialist ideals’ Only occasionally does the veneer crack quite dramatically. At one point Höss drags his children out of the nearby Soła River because the water is contaminated by the ashes from the chimneys (?). Throughout, however, the soundtrack tells the grim story of extermination through the sound design of Johnnie Burn and the avant garde score by Mica Levi.

I had two thoughts as I watched and listened. The first was in reaction to a comment by Hedwig about what they might do when the war ends. In many films set during the Second World War, characters rarely have time to think about the future since the present is so dangerous or desperate. The British ‘home front’ film Millions Like Us (1943) is unusual in presenting a discussion about how the post-war world will be different. But Hedwig has clear plans, most of which depend on Rudolf being promoted. She is not concerned about anything other than the likelihood of bourgeois comfort in the future. The second is the focus on the bureaucracy of genocide which reminded me of the film Occupied City (Netherlands-UK-US 2023) Steve McQueen’s partner Bianca Stigter has researched data which demonstrates just how well-prepared the invading German forces were in their search for Dutch Jews with the bureaucracy already set and functioning. In Glazer’s film we have the presentation by the builders/designers of the furnaces and later the large scale meeting at which Höss begins to lay out the logistics of organising the movement of 400,000 Hungarian Jews to camps and ‘creaming off’ the able-bodied for slave labour. On one of his moments of contemplation in Berlin, Höss attempts to calculate how gas would be needed to kill all the assembled Nazi dignitaries in the large hill he surveys from a mezzanine. It’s just an exercise for him. There is nothing banal about this for me. I find it terrifying. A little while after this Höss suffers some physical discomfort and the presentation then seems to imply that he looks forward into the future in which Auschwitz is a museum memorial. One review suggests that this view of the cleaners cleaning the site in preparation for the next day’s visitors is some form of cop-out by Glazer. I don’t see this.

The film depends to a considerable extent on its two lead actors, Sandra Hüller is one of Germany’s best actors and certainly one of the few who are widely recognised internationally. I read that she was initially unsure about taking the role because of her fears about appearing in a historical drama that revels in the period trappings of Nazi uniforms and regalia. But her role sees her confined to her home and surrounding countryside. I feel that she is rather drably dressed with her hair mostly tightly braided. Only occasionally does the character reveal the depths of the penetration of Nazi ideology: once when she models a fur coat taken from one of the camp’s victims and again when she tells a servant who has displeased her that she could have her ashes scattered over the countryside (something we see a worker doing in another scene. It’s a stunning performance by Hüller. Similarly Christian Friedel as Rudolf Höss is presented with the worst haircut I’ve ever seen but he does have the SS uniform and Glazer presents the massed ranks of such characters in Berlin, but there is no real sense of glamourising the SS. There are many other notable incidents in what is a richly detailed film written by Jonathan Glazer himself and drawing on extensive research.. I’ll just mention one – the obsession of Hedwig and Rudolf in their different ways with the garden and their flowers. I read once commentary that sees the couple as embodying a Nazi mode of living which embraced a form of return to nature and which Hedwig links to the ideology of ‘lebensraum‘ – the ‘room to live’ provided by the Occupation of Poland and other lands to the East. This meant that the people already living in the East were to be removed to labour camps and in the case of Jewish populations subjected to genocide.

I’m glad I have now seen the film and I think I now have another perspective on Nazi ideology and the crimes it emboldened.