Peter Watkins died aged just on ninety at his home in France late last year. He was a fine film-maker and agit provocateur whose politics and film style were too strong for the mainstream media. He leaves behind a limited number of works but several of which are key features in recent political cinema.

Watkins started making amateur films at the beginning of the 1960s. This led to him being recruited by the BBC; one of several young film-makers including Ken Loach and Ken Russell. After a probationary period he was allowed to make a documentary on the last battle fought on British soil; by the soldiers of the British monarch and highlanders following the ‘pretender – Bonnie Prince Charlie’; Culloden. The film, running 67 minutes in black and white, was based on John Prebble’s study of the same name. But Watkins introduced a radical form; having a contemporary reporter and film crew recording as part of the narrative. This was an early example of a new TV genre – docudrama. With a small crew and non-professional cast Watkins produced effective battle scenes intercut with interviews and comments by the C18th characters. This original and provocative film struck chords with both audiences and critics; it remains a seminal piece from the period.

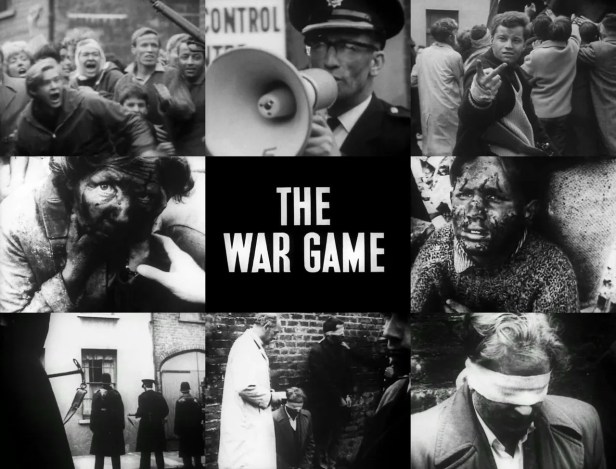

Watkins now went on to produce a documentary on the effects of a nuclear strike on Britain, The War Game. Just as effectively the production produced a dystopian vision of the aftermath of a nuclear device exploding in Kent. And Watkins continued the form of contemporary newsreel presenting what was an imagined catastrophe, though based on close research. Whilst the film went on to win an Academy Award and remains a classic tour-de-force, it was banned by the BBC at government pressure and only appeared on TV twenty years later. It did, and still does, get exhibited in cinemas.

Watkins resigned from the BBC and was able to direct a commercial feature about the world of pop music. Privilege (1967) stars contemporary pop star Paul Jones and contemporary fashion model Jean Shrimpton in a portrait of a pop idol used by the government and the media to promote conformity.

Watkins presents the fictional narrative with the addition of a cinema vérité style. The set pieces in the film, like a pop concert and then festival are very effective. But weaknesses in the script and of the stars make the film less effective. It was generally panned and the production companies gave it little access to exhibition.

Watkins now directed a feature in the USA, Punishment Park. The Park is question is where the US Government treats dissidents; here opponents of the Vietnam war. After military style trials the arrested activists are faced with a choice between imprisonment or the challenge of the Park. Here they must evade police and security for three days to reach a Stars and Strip flag at the centre. Both trials are obviously rigged. But both are also filmed by a team of European TV reporters, thus giving the feature a typical Watkins spin. Shot on 35mm, in colour and running 91 minutes, it remains one of the more widely seen Watkins films.

For much of his life Watkins lived and worked in Scandinavia and he was able to make a number of features there. The Gladiators / The Peace Game (Sweden 1978): The Seventies People (Denmark 1974): The Trap / Fallan (Sweden 1975): Evening Land / Aftonlandet (Denmark 1976: The Freethinker (Sweden 1984), all present topics in Watkin’s inimitable but developing style. And all of them are discussed in detail, the content, production and reception, on the Watkins Webpages; Films.

But there is one that deserves particular comment. This is Edvard Munch, a biopic of the famous/infamous Norwegian painter, noted for downbeat and expressionist work. Watkins researched Munch’s career and personal life and produced a portrait that studied the influence of the latter on the former. The masterly portrayal relied on non-professional performers and was presented with Watkins mixture of narrative drama, commentary and reflexivity. And the techniques of film and colour carefully mirror Munch’s panting style. It is one of his finest films and there is a power in the parallels between the lives of these two idiosyncratic and subversive artists.

At different times Watkins was involved in teaching at Universities. A key such action was at Columbia University in the 1970s. Watkins and the students came up with a critical analysis of the mainstream media, calling it ‘the Monoform’

With few exceptions, the Hollywood Monoform has been adopted by virtually all creators of commercial films, most documentary films, and by all aspects of television production including news broadcasting. This global adoption of one language form – in effect a standardization of the mass audiovisual media – is a central issue of the media crisis. It means, for example, that a documentary film can basically have much the same form and narrative structure as a Netflix drama series.

It is important to know that it affected the way Watkins made documentaries; confessing that his existing work itself suffered from aspects of the Monoform. And his future projects were produced with particular techniques aiming at confronting the Monoform.

This can be seen in The Journey / Resan (Sweden 1987). This is an epic work, running for over fourteen hours in 19 segments or chapters. This was a global peace film produced in 1983-86 by the Swedish Peace & Arbitration Society and local support groups in Sweden, Canada, USA, Australia, New Zealand, USSR, Mexico, Japan, Scotland, Polynesia, Mozambique, Denmark, France, Norway, West Germany, with post-production support from the National Film Board in Montreal, Canada. Watkins travelled round meeting and interviewing groups of activists and families, relying on local production crews. He also involved local people in several ,locations acting out scenarios like mass evacuation or fall-out shelter life in the event of nuclear disasters. The film addresses nuclear weapons, public awareness and the impacts of the nuclear and larger arms industries.

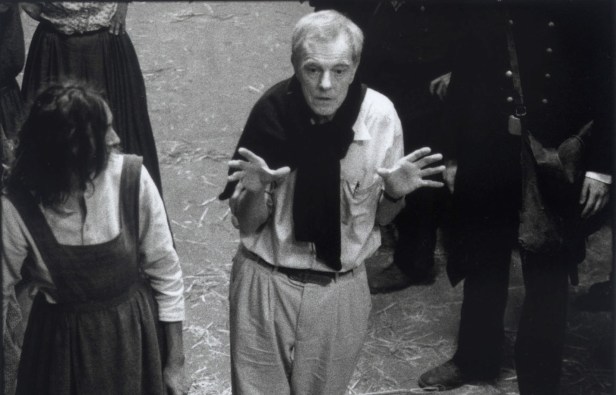

Watkins final film was a dramatisation of the 1871 Paris Commune, filmed in Paris with over 200 non-professionals performing as Communards, oppositional people and the reactionary National Government, La Commune (2000). Adhering to his general film form of his career the drama is presented by two journalists working for Commune TV with inserts from the National Government TV station. The participants both present their characters from 1871 but also comment on the contemporary world and the contemporary media, including the film in which they appear. This is supplemented on by on-screen titles of information and comment and voice-over comments by Watkins.

The French State had been defeated in a war with Prussia which now lay siege to Paris. The French Government’s capitulation was opposed by the majority of Parisians, led by proletarian ‘Red Clubs’ and a National Guard dominated by revolutionary minded workers. This led to the Commune, which ran from March until late May 1871.

Karl Marx, in his address to the International Working Men’s Association (May 1971) claimed

Lasting just 71 heroic days, the Paris Commune was the first ever attempt by the working class to take and hold power in the interests of the masses – the world’s first workers’ state.

Over two weeks Watkins, the cast and film crew created a five and half hour rendering the Commune, with a dynamic sense of the event whilst supplying comment on this seminal historical action. It was shot on 16mm and includes long tracking shots, face-to-face interviews and much of the drama of the months of revolution.

Watkins death is a loss but his career had completed. And the many tributes and obituaries suggest that much of his output will be available in some form. The ICA in London have already screened several titles. One would expect the BFI to organise a retrospective. Hopefully independent cinemas in Britain will also host this works. There are various DVD’s and Blu-rays of some of his titles; the main output is in the French Domaine Label in Paris. There are archive copies on both 16mm and 35mm of some titles, including at the BFI. And there are some titles, interviews by Watkins and multiple comments on his films on You Tube. Peter Watkins’s webpages have commentaries on all his films. And there is his critical statement on the Monoform.

A longer discussion of Watkins’ work can be found here.