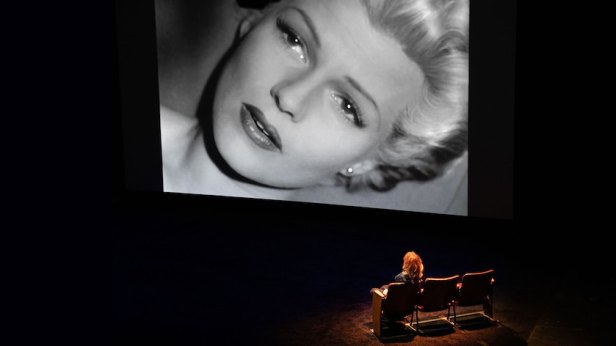

After the credits sequence filled with ‘images of women’, a woman then walks away from the camera towards a tented village and a title tells us it is the Cannes Film Festival. A cut to an interior of a theatre space reveals what appears to be a lecture, a kind of TED talk about visual language, not in Cannes but at the Cal Arts Theatre in California. The lecturer is the independent filmmaker Nina Menkes and she appears to be addressing an engaged audience. What follows is a conventional form of documentary in which Ms Menkes offers a commentary linking various film clips interspersed with ‘talking head’ interviews with other women filmmakers and academics/producers etc. and some group discussions. There is also a rather mesmeric score, seemingly riffing on Bernard Herrmann’s work for Hitchcock. It isn’t a ‘filmed lecture’ but rather a constructed film narrative setting out an argument linking three central ideas about visual language, the employment opportunities for (and discrimination against) women in the film industry and an environment of pervasive sexual assault and abuse. Although I know the name Nina Menkes, I don’t think I’ve seen any of her films (which I don’t think have been on general release in the UK). She has been making films since the early 1980s and in this film she references some of her own work.

The pitch of this ciné-lecture appears to be to a wide audience rather than to an artististic avant garde or the film studies academy. This is good in the sense that it is accessible to the widest possible audience but it also means that there is a danger of over-generalising some of the arguments and this can be seen as resulting in quite divided responses to the film from reviewers/critics and in some of the ‘user comments’ on IMDb. As might be expected, there is a clear gender split in some of the responses but others also point towards the decisions Ms Menkes makes in how to put together her argument. She begins by adopting and exploring the concept of the ‘male gaze’ as set out by Laura Mulvey in her 1975 paper on ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’, published in Screen. Laura Mulvey herself seems to be enjoying something of a ‘moment’ and the ‘male gaze’ is a concept that has been taken up by a wide range of younger women over the past few years. It even turned up as a question on University Challenge (UK TV) recently. Its circulation over the past fifty years is partly down to the growth of film studies and teachers looking for memorable phrases/terms to discuss with students. We see Menkes meeting Mulvey and then Laura Mulvey speaks to camera, confessing that she is surprised at the currency of the term she only used once. In fact she modified what she said in a 1990 essay titled ‘Afterthoughts on Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’. Other forms of ‘gaze’ were being discussed and feminist film scholarship moved on in different ways including work on melodrama and the women’s picture and on audience and reception studies. Mulvey in 1975 was writing at a time when psychoanalysis was infiltrating film studies and the study texts were often Studio Hollywood films of the 1930s and 1940s.

Nobody can dispute that Studio Hollywood was a patriarchal institution but it wasn’t all of cinema and within it there were female spaces and films that focused upon women (thus the work on melodrama in the late 1970s and early 1980s). As Menkes observes there were just two women working in Studio Hollywood as directors, Dorothy Arzner and Ida Lupino who barely overlapped timewise. Menkes uses the famous speech by Maureen O’Hara as a vaudeville dancer in Arzner’s Dance, Girl, Dance (US 1940) when she addresses the audience and chastises the men as voyeurs. A trivia note here is that Dance, Girl, Dance has three leading players. Alongside O’Hara are Louis Hayward, then married to Ida Lupino, and Lucille Ball who would later become one of the most powerful women and the great innovator of American television. It’s a good clip to show what women can achieve from behind the camera. Menkes then goes on to argue that in the current American film industries women comprise around 50% of graduates of film schools but only 8-9% of directors of mainstream US-produced films. This does suggest an institutional problem with US production companies and their funders. Perhaps a major flaw of Menkes’ argument is that most of her examples relate only to mainstream Hollywood. It would be interesting to see the figures for film schools and female directors for other major industries. In some cases there might be similar or much worse ratios but in others such as France there might be more women behind the camera.

The third part of the film’s argument is directly related to the issues taken up by the #MeToo movement including sexual abuse of women during the casting process or on set. Menkes offers us several examples of films which include scenes of non-consensual sexual activity or gratuitous exposure of women’s bodies. One of the interviewees is Rosanna Arquette looking back at a scene from Scorsese’s After Hours (1985). She refers to a scene in which her character is dead in bed and Griffin Dunne uncovers the body to reveal she is naked except for a pair of skimpy knickers. Arquette says she never thought about this exposure at the time. One of the other extracts is from Richard Fleischer’s Mandingo (1975). Menkes wants to make the point about ‘sex as power’ in a film where a white woman, the wife of a plantation owner in the ante-bellum South, in effect rapes one of her husband’s slaves played by Ken Norton the boxer. She makes the point well. However, she introduces the clip by quoting Roger Ebert’s review denouncing the film as ‘racist trash’. She apologises for using the clip, especially when it isn’t an ‘A List’ film. She doesn’t seem to recognise that although it was initially reviewed very negatively it was later recognised as an important film about slavery by some notable film scholars – and it was released by Paramount. It’s also interesting that she doesn’t mention Susan George who plays the wife in the scene and who was herself seen as being presented as a rape victim in a scene from Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1971) which was discussed at some length by the BBFC. There are several very interesting comments by interviewees in Menkes’ film including filmmakers such as Julie Dash and various academic and industry figures. I guess I’ve just picked out a decision that I found puzzling. But then discussions of what is acceptable or not acceptable at various times are very difficult to present in a context like this.

Overall I think I’ll stick with my initial thoughts on the film. I think that it works as an introduction to all three parts of the argument Nina Menkes wishes to make and that is useful if it makes the discussion more accessible for a wider audience. On the other hand, I think that she perhaps takes on too much of the argument for the 107 minutes she has available and it might be better to focus on one of the parts in more depth, though I can see that she might feel that all three parts must be viewed together. I don’t agree with all of the points made by Nina Mekes but this is a polemical piece and it does get people talking about a serious set of questions. I watched the film on BFI Player.