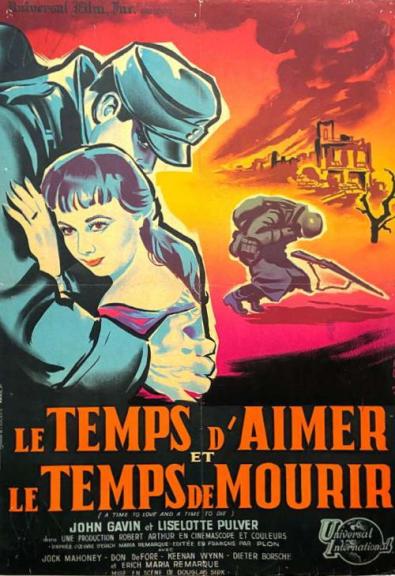

This is another film I had to miss on its limited UK release earlier this year. I was keen to see it for three reasons. I have enjoyed previous films by Katell Quillévéré, I admire both lead actors, and the narrative deals with that intriguing period of the immediate post-war years in France in the late 1940s and early 1950s and then into the 1960s. The story has been developed by the director and her co-writer Gilles Taurand from the story of the director’s grandmother as a 17 year-old during the German Occupation of Northern France in 1940. It becomes a form of melodrama and the director mentions the influence of Douglas Sirk’s 1950s Hollywood films as well as those of the more realist style of Maurice Pialat. She wanted a tension between these two different approaches. The result is a kind of realist melodrama which eschews the usual excess of emotion expressed visually and focuses instead on hand-held camerawork by Tom Harari and subtle art direction by Hélier Cisterne. The Sirkian feel of aspects of the film is embodied in the French title which actually translates as ‘The Time to Love’, riffing on the title of Sirk’s 1959 film A Time to Love and a Time to Die adapted from the novel by Erich Maria Remarque about the love of a German soldier on the Eastern Front in the Second World War for a girl back in Berlin.

The film begins with archive footage of the liberation of Northern France in late 1944 and the subsequent round-up of women accused of collaboration because they have slept with men from the German occupying forces. This shocking footage of l’épuration includes the public humiliation of women who are daubed with swastikas, stripped naked and hosed down. A longer lasting humiliation is their shaved heads. Only when we see a rapid camera tracking shot as two women run from their tormentors do we realise that this must be fictional footage edited into the archive. One of the women will prove to be Madeleine (Anaïs Demoustier) and we see she is pregnant. After the title credit the images switch to colour and a small boy running into the sea from a Normandy beach is rescued by a young man. The boy is Daniel, Madeleine’s son and she arrives to thank François (Vincent Lacoste), a student from Paris, studying archaeology. Despite their social differences, the single mother working as a waitress in a tourist hotel and the younger man from a wealthy industrial family in Northern France hit it off and begin an affair. It is a difficult triangular relationship. Daniel knows his father was German but he doesn’t know his name or whether he is alive or dead. Madeleine doesn’t want to tell him. François also has a secret that doesn’t emerge at first but she has some suspicions and her rift with her son doesn’t help François’ attempts to develop his relationship with Daniel. There seems to be a mistake in the dates quoted for the events that follow since if Madeleine was pregnant in 1944 and Daniel is 5 years-old when the meeting on the beach takes place it can’t be 1947 as the synopsis tells us. In the event this doesn’t matter too much as the narrative ends in 1962/3 when Daniel is an 18 year-old conscripted into the French Army post the Algerian War.

I searched hard to find reviews of the film and at first I was baffled by the lack of anything in Sight and Sound, once considered the ‘journal of record’ for reviews of important films like this. Eventually I discovered a short single paragraph in the June 2025 edition that wasn’t indexed. I don’t know if it was cut down from a full length review but the usually perceptive and reliable Philip Kemp describes the film as ‘gentle and poignant’. I will concede that the pace is slow and there is relatively little physical violence but there is a great deal of emotional violence and all three central characters are damaged by the situation they find themselves in. This period of French social history was not well covered at the time or for some considerable time afterwards. There was an overall conspiracy in French cultural life to perpetuate the myth that the French population under Occupation from 1940 to 1944/5 was divided between resistance fighters and collaborationists. The reality was that most of the population kept their heads down and survived the war and a minority were actively resisting or collaborating. Jacques Audiard’s film Un héro très discret (France 1996) featuring Mathieu Kassovitz was one of the first films to properly undermine this myth. Katell Quillévéré’s film shares certain key elements with Audiard’s earlier film, differing primarily in its approach and tone. I don’t want to spoil the narrative pleasures but I think I need to explain that the ‘secret’ that haunts François is that he is a closeted gay/bi-sexual man at a time when French law punished homosexuality severely. Three ‘damaged’ people attempt to create a conventional happy family in the context of post-war recovery and ultimately prosperity.

In the film’s press notes Quillévéré talks a little about her thoughts on melodrama:

The film is a variation on a genre: melodrama. It contains everything that makes a melodrama: characters who unite when the whole world is against them, a romance that moves back and forth between joy and distress, the constant threat of disaster . . . And at the same time, there’s a lot in the film that is contradictory to the genre, particularly its modest approach to emotion. The form does not impose emotion. Its aesthetic is often the opposite of what you’d expect from a typical drama.

She also discusses the attempt to avoid a costume drama approach, making the images appear ‘authentic’ but also filming them as though they are contemporary. There are a few scenes I would pick out to study and perhaps to compare with the films of a director like Sirk. One is an early sequence in which the flat in Normandy taken by the nascent family group is burned out in an arson attack in which François loses all the work he has done on his thesis. A different kind of disaster occurs much later when the family is now in a more upmarket flat in Paris. A Ming vase belonging to François is broken in an argument and he steps on the broken pieces cutting his foot. Between these two sequences the couple take a job running a bar frequented by American GIs. ‘Maddy’ has the hospitality experience and François speaks English and can act as manager. In this period, the couple become very friendly with a Black GI, Jimmy. This reminded me of another Sirkian link. In his ‘BRD trilogy’ Rainer Werner Fassbinder presents films that are part melodrama and part satire on the transition from the ‘rubble narratives’ of the immediate post-war in West Germany to the ‘economic miracle’ under Adenauer. Fassbinder ‘discovered’ Sirk and explored melodramas in two of which there is a Black American GI.

I won’t spoil any more of the plot lines of Katell Quillévéré’s film. I’ll only say that the performances of Anaïs Demoustier and Vincent Lacoste are excellent. They have to age over nearly 20 years and there are three young actors playing Daniel at 5, 10 and 18. I think that the mixture of ‘real’ and fictional story works very well for me. I have seen praise for the music – always an important feature of melodramas but I’m afraid I didn’t properly appreciate it on my TV set. The film is available to stream on a BFI Player subscription which is also accessible via Apple and Amazon. It’s good to see that the BFI are streaming it despite their rather insulting capsule review. Two of Ms Quillévéré’s earlier films are covered on this blog: Un poison violent (France 2010) and Heal the Living (France-Belgium 2016). I recommend them and her other feature Suzanne (France 2013). She is a major talent. Here is a trailer for Le temps d’aimer and a video in which the director discusses the film.