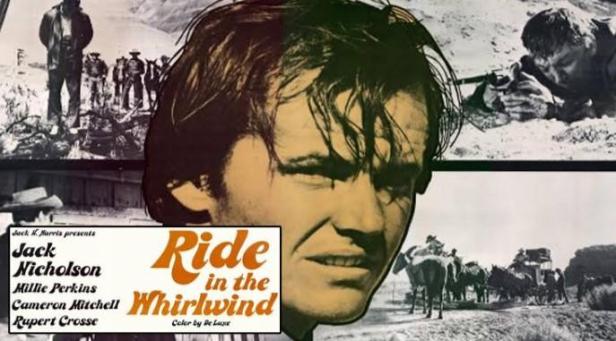

Here is a Western of almost mythical status based on the claim that it rejuvenates the genre just before the major disruption caused by the European Westerns of the 1960s reached American screens (although most American audiences probably saw the film after Clint Eastwood’s appearance as the ‘Man With No Name’ in 1967). It uses some of the elements that would become important in the European films but in many ways it is quite different. The enabler of the film is the legendary producer Roger Corman who set out to produce two Westerns using his familiar production approach. Both films were made by the same director and some of the same cast and crew members and they were completed in just six weeks for the pair. Director-editor Monte Hellman had a background which included work with the independent producer Robert L. Lippert who was known as ‘King of the Bs’ in the 1940s/50s. Next to Hellman, the other important figure was a young Jack Nicholson who had worked with Hellman before and now had parts in both films as well as being the writer of Ride in the Whirlwind.

The Shooting starring Warren Oates was the first film to be completed and Ride in the Whirlwind followed. Both films were intended to be just over 80 mins in length and filmed in colour on location in Utah with an overall budget of US $75,000 each. (IMDb suggests a longer version of the second film was released in France, the only territory with a cinema release, later in 1968). Ride in the Whirlwind opens with a pre-credit sequence in which a group of cowboys are waiting in a canyon for the appearance of a stagecoach which they proceed to stop. Their hold-up is botched with shots fired and a man killed. After the credits, the stagecoach reaches the next town but then a cut presents three different cowboys riding through the canyons. They are unnerved by one discovery before they come across a shack and a group of men who are recognisable as the outlaws who held up the stage. The only real clue to their identity is a man who appears to be the leader of the group and who wears a black eye-patch and is played by the great character actor Harry Dean Stanton. The three cowboys are suspicious of the welcome they receive but decide to rest overnight. The next morning the shack comes under siege by a large band of vigilantes out to catch the outlaw gang and dispense instant justice. The three cowboys are simply caught up in the fight despite their innocence. The main narrative question is whether the three innocent cowboys can escape and make their way back to Texas.

In the second half of the narrative the two cowhands who escape the shootout alive but on foot, Wes (Jack Nicholson) and Vern (Cameron Mitchell), manage to reach an isolated squatter’s cabin. The cowboys will have to become outlaws and hold the squatter and his wife and 18 year-old daughter (Millie Perkins) as hostages before stealing two horses in order to make a full escape. The vigilantes might appear at any moment.

I hope I haven’t given too many spoilers in outlining the very basic plot. You might wonder what makes this film special? I think it’s mainly the realism achieved in different ways. Nicholson reputedly took his writing role very seriously (he had already worked on the scripts for three earlier films) and spent a long time researching the ways in which the notoriously taciturn cowpokes talked to each other. He is said to have read several ‘dime novel Westerns’ to pick up typical language. At this point in his career, Nicholson was still only in his late twenties but he was already a seasoned actor with credits in TV series and low-budget cinema features. His big break would come with Easy Rider in 1969 and then the star status and Oscar recognition in the 1970s. At this point, however, he hadn’t developed his exaggerated mannerisms which undermined many of his later roles. He prospered in this role as Wes acting with the older Cameron Mitchell ,the nearly leading man and very dependable character actor who had starred on stage and would later develop a TV career. Dean Stanton (‘Harry’ came later) was another strong performer contributing to the ‘realist’ dialogue in a script that encouraged the ‘show don’t tell’ style adopted by Monte Hellman. The film does have a conventional Western music score by Robert Drasnin who was mainly associated with TV dramas but it is used carefully. There are whole sequences without music but with atmospheric sound effects, especially the wind through the grasses and the rocks and the sounds of insects.

Gregory Sandor worked as a DP for Monte Hellman three times, mostly I think on low budget and non-unionised shoots. Without a full crew he shot in available light which at times in the film achieves so-called ‘magic hour’ shots, capturing the odd beauty of the canyons. The camerawork also includes more long shots and big close-ups than were usual in most mainstream Westerns. As several commentators have pointed out the only false notes in the film concerned the overall appearance of Millie Perkins with what appear to be false eyelashes. There is nothing wrong with her acting performance, she just looks wrong for the West in the late 19th century. Perkins was actually born a few months before Nicholson and I think she must have had some drawing power (one of her first roles was in the Elvis Presley music drama Wild in the Country in 1961 and before that she had been Anne Frank in George Stevens’ 1959 picture).

Part of the fascination about the film and its mythical status is simply because of Monte Hellman. Hellman had started as an editor and then became associated with the directors who brought under the umbrella of Roger Corman. Hellman was a distinctive director in the making of his films and how he could talk about his work. Not surprisingly he found appreciation in France and would eventually see his work screened at Venice. His auteur status was achieved after the eventual cult success of Two Lane Blacktop (1971) which featured Warren Oates and the two music stars Dennis Wilson and James Taylor in a road race. As well as starring in The Shooting, Oates would appear in Cockfighter (1974) for Hellman. Oates also acts as a link between Hellman and Sam Peckinpah, being one of Sam’s regulars. Later Peckinpah had a small part in Hellman’s Italian-Spanish made Western China 9, Liberty 37 (1978). Watching Ride in the Whirlwind I was reminded of scenes from Peckinpah’s films. In particular, the scenario of the squatters cabin and the hostage situation reminded me of the ending of Ride the High Country (1961), the first Peckinpah film seen by Hellman (according to Hellman himself in an interview). Reversing the possible influence, the vigilante attack on the shack in Ride in the Whirlwind seems to have informed the similar sequence in Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973). In 1975, Peckinpah selected Hellman as film editor on The Killer Elite.

The Shooting and Ride in the Whilrlwind never received a wide cinema release outside of France (where the film appeared on the Cahiers du cinéma Top Ten for the year) but they did receive a Criterion Collection release on the same Blu-ray and two separate DVDs. Criterion included a range of extras and one, an essay by Michael Atkinson, is on the Criterion website along with a video discussion between Monte Hellman and Roger Corman. If you find the Atkinson essay a hard slog, Jeff Arnold’s blog is usually a good read on Westerns. Both Atkinson and Sheila O’Malley (see image above) discuss Hellman’s work in terms of his interest in Samuel Beckett, suggesting that the two Westerns and Two Lane Blacktop are influenced by Waiting for Godot. Ride in the Whirlwind is available in on many online platforms for free. I watched it on Talking Pictures TV’s ‘Encore’ catch-up service but it has since left there. The film is certainly worth digging out. It is spare, intelligent and realistic about the difficult lives for everybody on the frontier in the West. Unfortunately there are no decent trailers available. I have found a good print of The Shooting online so I’ll blog on that in a week or two.

Two Lane Blacktop was quite a ride. I must have seen it in 1971, I think, at a long-deceased cinema like the Plaza or the Tower in Leeds, sometime before I was quite attuned to the elliptical nature of indy film. I remember thinking something along the lines of ‘WTF was that ?’ once it had concluded with its two lead non-actors, James Taylor and Dennis Wilson, being rudely interrupted by the force of Warren Oates’ personality. No more films for Taylor or Wilson that I recall and perhaps deservedly so. Dennis had an ‘accidental’ drowning at age thirty-nine having spent the morning drinking on board a boat. Before that he was friendly with one Charles Manson who believed he might assist with Charlie’s music career. I think I read that the subsequent Sharon Tate slaying was a misdirected revenge attack on some record producer that had rejected Manson’s efforts.

LikeLike

Two Lane Blacktop was picked up by Rank for UK distribution and a certificate was issued in 1971. I saw it in 1973 at the Screen on the Green in Islington in a double bill with Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here. A great double!

LikeLike