Looking for a classic film to watch on iPlayer, I realised that although I had seen a few key scenes from Spartacus many times I had never watched the whole film. Watching it now over 60 years since its release I find it to be an engaging narrative but arguably lacking in depth and complexity and possibly more interesting in terms of its production context and reception. In some ways the production ‘tested’ several aspects of Hollywood in 1960. Unlike many of the ‘historical epics’ that appeared from the late 1940s onwards, including Samson and Delilah (1949) and Quo Vadis? (1951) and later The Robe (1954) and Ben Hur (1959), Spartacus was a literary adaptation of a recent novel and it was not a ‘runaway production’ made in Europe (though some battle scenes were shot in Spain). The rights to Howard Fast’s 1951 novel were acquired by Bryna, the company set up by the actor Kirk Douglas and named after his mother. He was eventually able to gain finance and a distribution deal from Universal, once a mini-major but now able to compete with MGM, Warners, Fox and Paramount after the majors had lost their cinemas following the late 1940s anti-trust rulings.

The shoot began with Anthony Mann directing but after a few days or weeks (accounts vary), Mann and Douglas fell out, seemingly because Mann felt he was being asked to make a ‘message picture’. Mann was not opposed to the message itself but preferred to ‘show rather than tell’. Another explanation offered by producer Edward Lewis was that Mann was frustrated by having to deal with four actor-directors (Douglas, Laurence Olivier, Charles Laughton and Peter Ustinov), each of whom attempted to challenge Mann’s interpretation of the script. Douglas as ‘Executive Producer’ then decided to offer the directorial role to the 30 year-old Stanley Kubrick, with whom he’d had a successful collaboration on Paths of Glory (US 1957). Kubrick later argued that Spartacus was the last picture on which he did not have overall artistic control, though there were possibly decisions that he took or rather forced through during the production. Overall, however, Spartacus appears to me as Kirk Douglas’s film adhering close to Dalton Trumbo’s script.

Outline

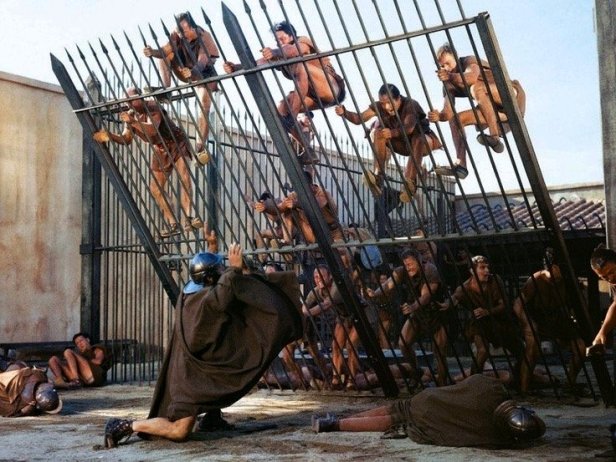

For anyone who isn’t familiar with the film, it is set in the first century BCE during the period of the Roman Republic (509-27 BCE). Spartacus is an historical character and there is an overall attempt to stick to the known aspects of the historical account but with some additional characters. There is a central narrative about a revolt of slaves which starts at the gladiatorial school in Patua, Southern Italy run by Batiatus (Peter Ustinov) where a Thracian slave, Spartacus (Douglas), is being trained. A secondary narrative concerns the relationship between Spartacus and a British slave woman Varinia (Jean Simmons). A third narrative strand is the battle within the Roman hierarchy between the traditional military leaders led by Crassus (Laurence Olivier) and the senators led by Gracchus (Charles Laughton). The three strands are interwoven into a conventional linear narrative.

The strengths of the film are, in my view, the cinematography and the casting. The film was shot using the ‘Super Technirama 70’ process. Technirama was a process formulated by Technicolor that followed Paramount’s introduction of VistaVision by running 35mm film stock horizontally through a camera rather than vertically. Utilising a new lens, the image was squeezed to produce a squarer negative in a 1.5 to 1 ratio. The resultant image was ‘unsqueezed’ to create a widescreen image to be projected via the conventional practice of vertical running through the projector. Like VistaVision, the screen ratio could vary as required for exhibition. The TV print I watched appeared to be using a ratio of 2.20:1. ‘Super Technirama 70’ was a later development which attempted to exploit new exhibition practices from the late 1950s and into the 1960s, ‘blowing up’ the high quality Technirama image for 70mm projection in ‘roadshow’ presentations (see below).

The cinematographer credited was Russell Metty, a distinguished craftsman who had worked with Orson Welles and who in the 1950s was best known to me for his work with Douglas Sirk at Universal, work which was notable in the development of colour photography in melodramas. Unfortunately, Kubrick also had a background in photography and reports suggest that he increasingly moved to marginalise Metty and focus on his own ideas about the look of the film. I respect Kubrick’s undoubted skill as a director but I’ve never been a fan as such and refusing to work with Metty and failing to make use of the more experienced man’s ideas seems typical of Kubrick’s behaviour. Ironically, Metty was awarded his sole Oscar for his work on the film. Spartacus does use the Technirama process to enable ‘very long shots’ of the opposing armies in the battles later in the film but some critics argued these were not effective. I was also struck by the contrast between the location work (mostly in California, but also in Spain for some battle scenes) and the studio work for some night-time and more intimate ‘outdoor’ scenes. Again the high definition of Technirama emphasises the disjunctive feel of location v. studio work. I was reminded of a similar disjuncture in Ford’s The Searchers (1956). I should also note that Anthony Mann supporters see his work on the opening scenes as much more compelling in terms of composition.

Some of the other technical credits also suggest the possibility of a clash between Kubrick’s ego and veteran filmmakers from Studio Hollywood. An example might be Andrew Golitzen as art director/production designer, though I have no evidence of any clashes with Kubrick. Robert Lawrence as film editor was less experienced but he went on from Spartacus to work on the two Anthony Mann epics made in Spain plus Nicholas Ray’s 55 Days at Peking. It would be fascinating to learn what he made of his experience working with three very different directors. The music score for Spartacus is by Alex North, another distinguished craftsman sometimes described as ‘left field’. I wasn’t sure about his score for Spartacus at first (while recognising that my TV set doesn’t offer the best sound quality) but by the end of the film I thought it worked very well. North was another who suffered later at the hands of Kubrick who ditched his score for 2001 (US 1968) without discussion.

The cast of Spartacus was also changed after the arrival of Kubrick. Jean Simmons replaced the German actress Sabine Bethmann as Varinia. Even so, some notable actors associated with Mann were kept on including John Ireland as one of the loyal supporters of Spartacus and Charles McGraw as the slave-trainer. Woody Strode has a brief but important role and 1960 would mark the year he broke through to larger roles such as the eponymous character in John Ford’s Sergeant Rutledge. In general, the Roman senators/leaders were played by Brits, apart from the rather wooden John Gavin as Julius Caesar. Gavin seemed to me to be much more animated in his roles for Douglas Sirk in the late 1950s. He would be one of the current or ex-Universal players in the cast alongside Nina Foch and Tony Curtis as Antoninus, the slave of Crassus who escapes to join Spartacus. Poor Herbert Lom plays a North African pirate, repeating a similar Moorish villain role a year later in El Cid.

One of the most intriguing aspects of the film is the script. Howard Fast was a very successful novelist with a writing career lasting from the early 1940s up to the publication of his final novel in 2000. Always left-liberal, Fast joined the American Communist Party in the 1940s, a move which led to surveillance by the FBI (Fast worked as a scriptwriter for Voice of America in wartime) and a brief prison sentence for contempt. Like most international socialists, Fast left the Party in 1956 at the time of the Hungarian rising and the revelation of Stalin’s actions up to his death in 1953. Fast had already had a novel adapted for the screen, Rachel and the Stranger in 1948, and he also contributed to a TV drama series in 1955. From 1957 he moved to California and continued to publish stories/novels under various pseudonyms. There is no suggestion his politics changed, so the question arises, why did Kirk Douglas reject Fast’s attempt to adapt his own 1951 novel, Spartacus? Presumably it was simply a bad script? Douglas turned to a more experienced screenwriter Dalton Trumbo who had been one of the ‘Hollywood Ten’ who had been imprisoned for contempt (refusing to co-operate with HUAC) for several months in 1950. Trumbo continued to sell scripts throughout the 1950s, even when blacklisted. He negotiated ‘fronts’ and used pseudonyms. Was his script more or less ‘political’ than Fast’s? I don’t know, but it does seem to me that Trumbo’s script doesn’t really bring out the revolutionary possibilities of the scenario and certainly doesn’t present Spartacus as a revolutionary figure. Of course this didn’t prevent Hedda Hopper, the notorious Hollywood gossipmonger from declaiming that no-one should go and see this ‘commie’ film. I also accept the argument that in the early 1960s some audiences may well have noted the allusions to the civil rights struggles of the times. Douglas did challenge and in effect defeat the blacklist by allowing Trumbo his full onscreen credit.

The film also suffered from the pressure put on Universal by the now declining Production Code Administration and other bodies to remove lines of dialogue thought unacceptable. The most laughable decision was the removal of the scene between Olivier and Curtis in which the older man enquires as to whether his slave prefers ‘oysters or snails’. But despite all this, the film was successful at the box office and a favourite film for some. Its reputation has been both boosted and possibly damaged by the scene in which the defeated slaves attempt to save Spartacus by each shouting “I’m Spartacus” when Crassus promises to spare them from crucifixion if they identify Spartacus. This could be a symbol of solidarity and collectivism but over time it has become a potentially comedic moment, especially after Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1979) effectively spoofed the statement having men being crucified shouting “I am Brian” when the character has been declared as ‘freed’.

In a way Spartacus is both a very American movie but also an unusual American movie. A ‘little man’, a slave in the Roman Empire, stands up for his rights – but in the end he loses. In fact the triumph of the film’s villain, Crassus will in turn lead to the end of The Roman Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire, a potentially more autocratic institution. But perhaps I am wrong and the people who love the film feel inspired by it.

I’m probably in a small minority but I prefer the films of Anthony Mann to those of Stanley Kubrick. I’ve already blogged on El Cid and I intend to write about The Fall of the Roman Empire. I think these two films are superior to Spartacus in several ways. El Cid has grown in its international reputation and perhaps one day Mann’s achievement with The Fall of the Roman Empire will be more widely recognised. I’ll remember Spartacus for the pleasure of watching Peter Ustinov, Charles Laughton and Jean Simmons. Tony Curtis has a difficult role but I have a soft spot for him too. Kirk Douglas is resolute throughout. As several critics note, he doesn’t speak many lines across the 180 + mins of the film and apart from his desire for a son who will be ‘free’ with Varinia, he appears a lonely man.

Here’s what I assume was the 1960 trailer. The film was restored, with cut sequences back in place, by Robert Harris in 1991 for a re-release. The full version now available includes the roadshow Iverture and closing score.

There has been a great deal written about the film, its production and reception and there is a useful short film on the 1991 and 2015 restorations of the film:

The Anthony Mann material is mainly taken from Anthony Mann, Jeaninie Basinger, Wesleyan University Press, 2007