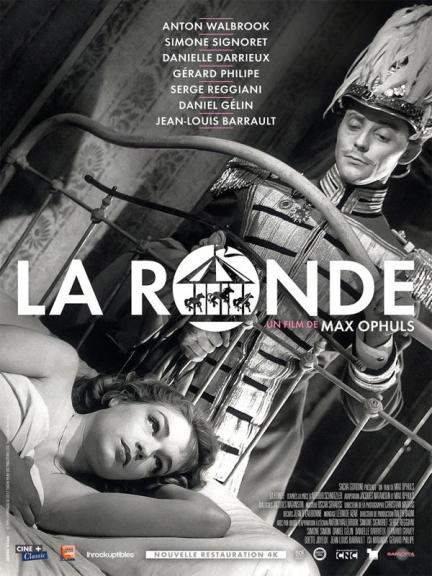

I think La ronde might have been the first Max Ophüls film I watched back in the early 1970s. Later I would use the opening of the film narrative in my teaching simply because it is one of the most audacious openings I know for the choreography, the set and the camerawork and the performance of Anton Walbrook as the ‘MC’. It also sets up the distinctive narrative structure. Now I have watched a restored version of the film and it has ‘blown me away’ in terms of Ophüls’ creativity and skills as well as the stunning cast of French cinema icons. It’s also very enjoyable in its critique of Viennese society at the turn of the century (as well as the contemporary cinema of 1950).

La ronde sees Ophüls back with the kind of material that informed his early cinema projects – Arthur Schnitzler’s 1897 play Reigen. The adaptation by the director himself and his co-writer Jacques Natanson adds a significant new character to the ’round’ of lovers. This is Anton Walbrook (an addition which alone elevates the film above expectations) who plays the ‘ring-master’ of the circle of lovers and pops up at each changeover of couples as well as making comments on the show so far. The continuous ’round’ of sexual pairings (disguised as ‘l’amour’) involves five women who each spend time with two men. This then means five men and ten couples in all. The ’round’ begins and ends with the street prostitute Léocadie played by Simone Signoret who first goes with the soldier Franz and completes the circle with a senior officer ‘le comte‘ (Gérard Philipe). Signoret’s two soldiers represent the breadth of the class system in the military and other pairings represent similar oppositions of old and young, rich and poor etc. It seems unfair to pick out any specific actors and they all get a similar amount of screen time. I’m always ready to watch Danielle Darrieux and Simone Signoret but this time I was surprised to find that Simone Simon as Marie caught my eye the most. Miranda Isa is the great Italian star who was the lead in Ophüls’ La signora di tutti (Italy 1934) and here she plays the the leading lady of the theatre who beds both the poet (Jean-Louis Barrault) and le comte. The young players here are Daniel Gélin and Odette Joyeux and the older man, husband of Darrieux’s Emma Breitkopf is Charles (Fernand Gravey).

The critique of Viennese society is delivered in two ways. It is there in the interactions of the couples. For instance, a delicious scene sees Emma and Charles Breitkopf in their adjacent single beds discussing the morality of infidelity while feigning any experience of such shocking behaviour when both are indulging in it themselves but ironically each are only shown with a single, younger partner. They are the only married couple in the narrative (i.e. their ‘other’ partner is the one they are married to) and their first names remind us of the married couple in Flaubert’s Emma Bovary. The satire is also highlighted by the commentary of the ‘raconteur’. Anton Walbrook is a true ‘Viennese’ whose comments are as subtle as a slight movement of an eyebrow or as caustic as an aside which refers to the age difference between lovers. The raconteur in fact plays many characters, linking all the trysts and manipulating events and characters to ensure the round is completed. At the beginning of the narrative he comments on the fact that his narrative is set in the past which he prefers to the present as it is ‘safer’ and which is more certain than the future. But the satire does extend into the future and to other societies – ‘love’ does after all make the world go round, but some societies are less inclined to recognise what really happens.

I wonder how much Ophüls himself felt liberated on his return to France from Hollywood? All his American films were handled by Universal-International even though they were made by independent producers. Increasingly the studio tried to reign in Ophüls’ seemingly extravagant shooting style – though in reality he was very efficient in his use of resources. Once back in France and working on a large scale set in a Paris studio, the director could return to his signature style. He was also free of the Hollywood Production Code. Although La ronde shows little overt sexual activity and no nudity, the script would have not got past the Breen office and the film includes a short scene in which the raconteur suddenly finds a roll of film and a pair of scissors so he can announce the censorship of one particular sequence. This is one of a couple of scenes which seem to be anachronistic in terms of Vienna in 1900. Cinema had been a ‘thing’ for around four or five years in 1900 but of course features were not yet being developed beyond a few minutes. A rather more plausible representation of the modern comes with scenes of cycling and early motor vehicle rides, but even so the appearance of a modern-looking sports/touring bike on a carousel is surprising. (I did research this and there is some historical truth in such a bicycle, but I’m not sure about its appearance on the carousel.) I realised later that we had already been introduced to studio film cameras and sound/lighting rigs at the start of the raconteur’s introduction as he surveys his theatrical set. This is an example of applying anachronistic technology references in an historical narrative, something that would become more familiar in the 1960s and after. More importantly, however, the American authorities did find La ronde troubling and in 1954 it took a Supreme Court judgement to finally release the film from the charge of ‘immorality’ pursued by censors in New York. The film did however receive two Oscar nominations in 1952, so it must have been seen in the US in 1951 unless the Academy’s rules were not so tight then? Andrew Sarris, the main American supporter of Ophüls in the 1950s, explains the whole issue of the New York censorship in a later Village Voice article. Meanwhile, in the UK the film was released in April 1951 at the Curzon in Mayfair where it broke records despite an ‘X’ Certificate. Strangely, I have been unable to find a revue in Monthly Film Bulletin or Sight and Sound in 1951. The BBFC suggests that cuts were made for a UK release but still gives 93 minutes for its length. The French restoration on Blu-ray is 97 minutes? The version I watched was 92 minutes. I’d love to know what might have been cut.

Geoffrey Nowell-Smith in Film Quarterly 2009, Vol 62, No.3 (Spring) argues that La ronde is not satire like the original Schnitzler play. He argues that Ophüls’ presentation “is a world viewed ironically and from a distance, and one in which the characters play out a destiny already written for them by the author and foretold to the audience”. I’m not sure why this means it stops being a satire, especially if it is read as also referring to contemporary French (and American) society. However, Nowell-Smith does point out that Schnitzler, whose play was banned in various countries, including the UK for many years, did include the the identification of ‘la ronde’ as a means of spreading syphilis or gonorrhoea. The dangers to soldiers in the First World War, as well as to civilians, provoked governments to attempt to protect the population via issuing warnings and prophylactics. La ronde is too playful for this kind of direct reference. However, I seem to remember that when I first heard about the film in the early sixties I was aware it had a ‘reputation’ – perhaps I was confused by the version directed by Roger Vadim released in 1964? I don’t think I’ve seen the Vadim version, though I probably knew about it.

Another aspect of the film that surprised me was the Oscar Straus music. I realised that I knew the music and found myself humming along as Anton Walbrook sings/’talks’ the words of ‘La Ronde de l’Amour’. But of course for most cinephiles the achievement of the film is Ophüls’ handling of the set constructed by Jean d’Eaubonne and his team and the choreography of the actors. The DoP on the shoot was Christian Matras. Up until this point Ophüls had used German cinematographers for most of his films, including Eugen Schüfftan and then Franz Planer for four of his Hollywood films. There is a quote from Jean-Luc Godard in Cahiers du cinéma in 1957 that suggests that French cinematographers only seemed to be ‘brilliant’ with the best directors but disappointing with others. The Cahiers writers approved of Ophüls so Matras was deemed to do very well. I have often wondered about the relationship between Ophüls and his DoPs. He does demand such complex camera movements which they need to research carefully. Apart from the glorious tracking shots and the noirish imagery, Ophüls also employs some expressionist tilts on this film.

There is a lot more to say about La ronde – and much has been written about the film. I will return to Ophüls.

This trailer was used in the campaign to save the Curzon Mayfair cinema. It’s very good but I have one complaint – it names several of the stars but leaves out Simone Simon.