This film has received much attention since its release in 2024, made in the USA with funding also from Britain and Canada. It has performed well among critics and at award ceremonies: notably at the Venice Film Festival, the Academy Awards and the Golden Globes. Also it has taken over $45 million [or equivalents] at the box office, this on a budget of about $10 million. This is a film that runs for more than 200 minutes though it does have an intermission, something that contemporary long films often eschew. Equally interesting is that it is one of those declining number of features that rely on filming in celluloid; and the sources for this are super 16mm, super 35mm, Techiscope and (most interesting) VistaVision. Like IMAX film VistaVision runs through the camera horizontally rather than the usual vertical, this enables a higher area of the frame exposed and a finer-grained projection print. VistaVision was only around for a few years in the 1950s and 1960s when widescreen formats came in. It has however continued to be used in production on occasion because of the high resolution. As far as I know there is nowhere in the world were you can actually see VistaVision prints; the Widescreen Weekend feature on VistaVision this year used either 35mm prints or 70mm prints running vertically. When it was used for exhibition most commonly the VistaVision master was copied onto 35mm prints running vertically in projection. For this title the various film formats have been copied onto both 35mm and 70mm prints and also transferred onto digital. VistaVision was actually shot producing an aspect ratio of 1.5:1 but exhibited in either 1.66:1, 1.85:1 and 2.0:1. The Brutalist has opted for 1.66:1, but I have not seen an explanation for that choice. Note, the completed film also includes short sequences shot digitally or with digital Betacam. The 70mm print comes closest to reproducing the quality of original VistaVision.

The narrative of the film is divided into three parts. Part 1 The Enigma of Arrival follows László Tóth (Adrien Brody), a Hungarian-Jewish architect and Holocaust survivor of the Buchenwald concentration camp who emigrates to the USA. The film has a fairly subjective style, so the opening sequences concentrate on László as he explains his situation, which includes being separated from his wife Erzsébet (Felicity Jones), a journalist who has survived the Dachau concentration camp. In the USA László travels to Philadelphia and stays with his cousin Attila Miller (Alessandro Nivola) who runs a furniture business. Attila has assimilated to US culture including converting to Roman Catholicism. Attila introduces László to the wealthy Van Buren family and he designs a new library/study for the patriarch Harrison Lee Van Buren (Guy Pearce). This goes badly wrong and then Attila and his wife turn on László. László now takes on labouring jobs and also acquires a heroin addiction. He becomes friends with an African-American labourer Gordon (Isaach de Bankolé) and his young son. Then Harrison Lee Van Buren re-appears, having come to regard the library study László designed and supervised and also having discovered that László is a experienced pre-war European architect with a reputation. Van Buren commissions The Van Buren Institute, a community centre comprising a library, theatre, gymnasium, and a chapel. Work begins immediately with László living on site and employing Gordon. Van Buren’s lawyer expedites the passage of Erzsébet to the USA, accompanied by her niece Zsófia (Raffey Cassidy), rendered mute by her experience in the Nazi holocaust.

After intermission the film continues with Part 2 The Hard Core of Beauty. The narrative focuses on the building of Van Buren’s institute with László experiencing difficulties working with the construction firm and, sometimes, arbitrary changes proposed by Van Buren. He is reunited with Erzsébet, now confined to a wheelchair through illness and Zsófia lives with them. He continues his friendship with Gordon and his son. Meanwhile he experiences rather subtle prejudice from the Van Buren family. Then a train accident brings the construction to a halt and the project is cancelled. László finds work in New York as a draftsman and Erzsébet works for a newspaper. Zsófia recovers her ability to speak and marries; then she and her husband decide to emigrate to Israel. They try to persuade László to follow suit but he sees no good reason to do so.

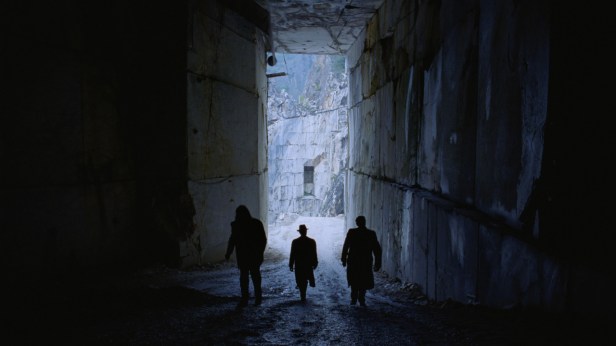

The work on the Institute recommences. Laszlo and Van Buren travel to Italy to select marble for the centrepiece altar in the Chapel. At an evening party at the marble quarry Van Buren sexually assault Laszlo adding pejorative comments. Laszlo’s addiction worsens after this. At a visit to the Van Buren mansion Erzsébet accuses Van Buren in front of his family. Then she persuades Laszlo to follow Zsófia to Israel. The Institute is later completed; Van Buren seems to disappear, but this is left ambiguous.

Epilogue: The First Architecture Biennale

In 1980, Erzsébet has died, and a retrospective of László’s work is held at the Venice Biennale of Architecture. He attends in a wheelchair, apparently now unable to speak. Zsófia delivers an address on is behalf and the camera tracks round the exhibition showing Laszlo’s later work.

Much has been written on this film so I will concentrate on the aspect that most impressed but also concerned me. I was able to see the film in a 70mm print at the Barnsley Parkway, the only cinema outside of London and Glasgow to screen the print so far. That itself is a bit of a mystery, why has the Media Museum’s Pictureville in Bradford only now arranged a screening? The quality of the image was excellent though I wondered about the choice of 1.66:1 aspect ratio; 1.85:1 would have suited the architecture better. The subtitles for the non-English dialogue were in yellow but no easier to read than the old-fashioned white ones. I found the soundtrack problematic. Some of the dialogue lacked clarity, a contemporary issue. And I thought the music was over the top; at times it drowned out the dialogue. And there is a long final sequence in Part 2 as the camera prowls inside the unfinished Institute which I found portentous. The Academy Award puzzled me.

The script was written by Brady Corbet and his partner and fellow-film-maker Mona Fastvold.

It seems that the character of Laszlo, and in particular his career, bears some relationship to actual Hungarian Jewish architects, but their biographies differ from that in the film so one can treat Laszlo as a fictional construct. Thus the events portrayed in the film are the choice of the writers. They have also chosen to present this narrative from a very subjective standpoint. The opening presents Laszlo recounting his travails in reaching the USA to an unseen observer or friend and most of the rest of the film is from his point of view, though using an observer stance rather than POV camera.

The design and costumes are excellent and appropriate to the period. The architectural sets and props are impressive. However, we only see the work that Laszlo designs for Van Buren, his study/library and the Institute. We also see some furniture in Miller’s showroom, and one Bauhaus item of furniture: and examples of Laszlo’s pre-war architectural work in magazines held by Van Buren. In the epilogue we see illustrations and photographs of Laszlo’s architectural designs after the main story at the biennale. The Institute dominates this, an impressive design and towering construction. We do see some contemporary construction when Laszlo is working as labourer in the construction industry.

The cinematography by Laurie “Lol” Crawley is very fine. His filming for The Brutalist won him both an Academy Award and a BAFTA. He has worked with Corbet before and has worked with both 35mm and 65mm film. The Brutalist includes both VistaVision copied to 70mm: 16mm for the insert shots of contemporary newsreel and ‘life’ material: plus brief use of digital and analogue.

The VistaVision material looks really good; I have not seen the digitised version and I wonder how that transfer works. The film does have a lot of low key lighting which does not exploit the VistaVision format quite as well. There are several impressive sequences of combined low and high key lighting with tracking cameras; the final search of the unfinished Institute is an especially fine visual presentation. Much of the film though follows the dominant mode in commercial film in the use of master shots, dollies and tracks and close-ups.

The cast are fine, especially Adrian Brody and Guy Pearce. I read that Brody and Felicity Jones had ‘help’ from an AI application with accents; the dialogue includes English, Hungarian, Italian, Hebrew and Yiddish. They sound convincing. As I mentioned though the soundtrack does not always offer clarity for dialogue and the music certainly drowns it out on occasions.

The content of the narrative does seem problematic to me. The subjective nature of the film means that the wider world is vague or ambiguous. The contemporary newsreel and life material gives a sense of the culture of the 1950s but not of the politics or economics. Thus there is no reference to the war by the US allies in Korea. And whilst Gordon and his son provide an African-American presence there is no sense of the developing civil rights movement. Presumably the audience is supposed to see Laszlo and Gordon as both victims of US prejudice, but without a proper context. The exception to this is the positive reporting of the erection of what is called an Israeli state, [a colonial occupation]. Despite being a secular Jew, Laszlo does attend a synagogue and we hear a welcoming report by a Jewish 0rganisation, which seems to be a pro-Zionist one. According to Middle East Eye it is actually,

In the first part of the film, an infamous 1948 radio broadcast by Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, declares the birth of the state of Israel with Laszlo listening.”

But we do not hear at all about the Nakba or the subsequent Zionist wars against Palestinians and Arabs, certainly not the infamous collusion with Britain and France over the invasion of Egypt to seize the Suez canal. And there is no reference to the Jewish intellectuals in the USA who, at the time, warned where the colonial settlement would lead; in fact turning out far worse than their prognostications. The use of the founding of a colonial state in Palestine ties in to the later issue of migrating to Israel; reinforced again in the epilogue with Zsófia’s presentation. This draws in The Holocaust, a now standard use of the Nazi holocaust to justify the Zionist occupation. Norman Finkelstein makes the distinction between the ‘nazi holocaust’, the historic event; and ‘The Holocaust’ using the former as in the political expression of Zionist interests and values.

In a Press Conference at the Venice Film Festival Corbet commented,

The film is about a character who flees fascism only to encounter capitalism. That’s what the movie is about, he said.” (Middle East Eye).

But the film is not seriously anti-capitalist. What we see is a a wealthy capitalist family, all of whose members are prejudicial and antagonistically class conscious. How their wealth was expropriated and from whom is not clear. And we a see another Jewish migrant who succumbs to the US culture of the 1950s by evacuating his Jewishness. But there is not treatment of the operation of capital. This is a typical Hollywood critique which uses undesirable individuals rather than treating the system and the culture.

The same problem is encountered in the treatment of the Brutalist movement. Apart from Laszlo’s design for the Institute we do not see other examples of Brutalist projects until the epilogue. There is a mention of the Bauhaus and an example of Bauhaus furniture but little else. The Brutalist movement only started in 1950 though it spread quickly. Laszlo’s earlier architectural designs, only seen in the journals, are not really Brutalist. The epilogue presentation ties his later design work to his experience in the Buchenwald concentration camp. But there are no other examples of work by architects in the movement. And there is not really an explanation in the film of what constitutes Brutalism; including how it took forward ideas from the Bauhaus about simplicity and community.

The film really relies on ambiguity in its treatment of architecture, prejudice, US culture and (even more) US capital. Yet this is not a biopic of an historical person, so all these facets (or lack of them) in the film are choices, mainly by Brady Corbet as writer and director. I came out of the screening feeling rather dissatisfied. It is worth watching for the visual treat but I do not quite buy the hype that has accompanied the release of the movie. Whilst it offers the virtues of Hollywood production values it also suffers from the limited narrative form of the Hollywood movie.

ReferenceFinkelstein, N (2000) The Holocaust Industry: Reflections on the Exploitation of Jewish Suffering, London, Verso.

the twenty minute interval baked into this film, while very welcome, only reinforced for me the fact that I had another hour or more in the company of these largely disagreeable people and a very rambling storyline. I rather like Brutalist architecture and spent many a happy hour in the splendid Westgate Pool in Leeds before it was unceremoniously torn down to make way for another car park. That was not enough to save this film for me.

The promotional push for this epic seemed reminiscent of the Weinstein days of self promotion. What most amazed me about the story in reflection was that, although we caught a glimpse of a much diminished Laszlo in the epilogue, we were given no opportunity to catch up with the character and his thoughts on the past.

I saw it at Showcase Birstall. Digital I would imagine.

LikeLike