The ‘Three Colours Trilogy’ proved to be a major project in the development of what might be termed ‘international arthouse cinema’. The three films directed by Krzysztof Kieślowski are currently streaming on MUBI. In 2010 I used the first film in the trilogy, Three Colours Blue in an Evening Class course about ‘Music in Film’ and a slightly amended version of the notes I produced then are offered here. Time permitting I will try to post something on the other two films in the trilogy later.

Background

The ‘Three Colours Trilogy’ proved to be a major project in the development of what might be termed ‘international arthouse cinema’. The three films directed by Krzysztof Kieślowski are currently streaming on MUBI. In 2010 I used the first film in the trilogy, Three Colours Blue in an Evening Class course about ‘Music in Film’ and a slightly amended version of the notes I produced then are offered here. Time permitting I will try to post something on the other two films in the trilogy later.

Background

In the early 1990s, Krzysztof Kieślowski (1941-96) became the leading auteur in European Cinema – the director whose films would be most eagerly sought by distributors and whose name would guarantee audiences in cinemas. His was by no means an ‘overnight success’ since he had begun his directing career in 1969 on graduating from the famous Lodz Film School in Poland. He was first a documentarist and worked in Polish television. It wasn’t until 1979’s Camera Buff and his move into fiction that his work began to be seen outside Poland. His international profile was finally established by the series of ten one hour films for Polish television, Dekalog (1989-90), which achieved theatrical screenings internationally, two of them being extended into feature length as A Short Film About Killing and A Short Film About Love.

During the difficult days of working in the Polish media before the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, Kieślowski’s work explored Polish life in the context of an oppressive regime. After Dekalog he received the support of the French producer Marin Karmitz and, despite the language difficulties between the two men they quickly formed a partnership which delivered Kieslowski’s last four films, each made as international co-productions with a French-speaking leading actor.

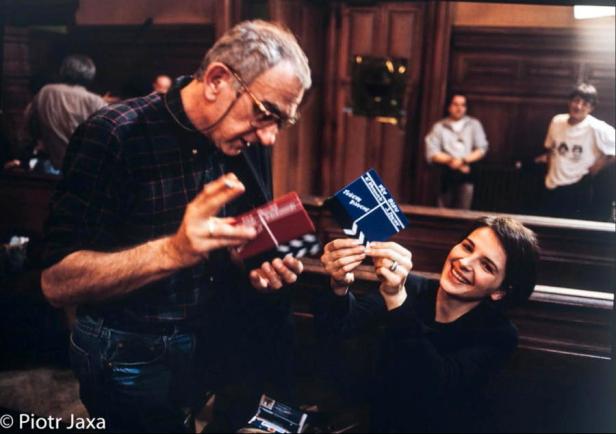

Just like Alfred Hitchcock and many others, Kieślowski had his close collaborators, the principal two being writer Krzysztof Piesiewicz and composer Zbigniew Preisner. Cinematographer Slawomir Idziak (who had worked on earlier films with Kieslowski) is an important contributor to Bleu, but the other two films in the trilogy were shot by different cinematographers. Kieślowski was lucky to find three Polish cinematographers working in an international context. With a mainly Polish creative team, producer Karmitz suggested that the film had a strong Polish perspective on French life – something that he was able to slightly change as the production progressed such that the film worked as an international production.

The trilogy

The idea for the trilogy came from Krzysztof Piesiewicz who suggested repeating the idea of the Dekalog (which had used the Ten Commandments as a starting point), but this time taking the French flag and its embodiment of the revolutionary ideals of liberté, égalité and fraternité. The intention was that these concepts should not be explored on a political or philosophical level, but on a personal one. Bleu is intended as a film about liberté, but specifically about ‘emotional’ liberté. Julie, who suffers a double tragedy at the beginning of the narrative, must find the ‘freedom’ to love again, even to ‘live’ again (as distinct from the freedom to do only what she wants – which the film suggests is no freedom at all). On a second level, the film is about European unity and how it can be expressed through music, so Julie will find her personal liberté through accepting her role in creating the music. The two films that follow star Julie Delpy in Blanc and Irène Jacob in Rouge. Both Juliette Binoche and Julie Delpy appear briefly in their respective ‘other two’ films, but otherwise the stories are not directly connected.

The music The music which Julie must help produce is ‘Song for the Unification of Europe’, based on the Greek text of ‘1 Corinthians 13’ and composed by Zbigniew Preisner. Preisner and Kieślowski had a close working relationship and they invented an eighteenth-century Dutch composer ‘Van den Budenmayer’ who is credited with some of the music in their films. Wikipedia’s entry on Preisner tells us:Zbigniew Preisner studied history and philosophy in Kraków. Never having received formal music lessons, he taught himself about music by listening and transcribing parts from records. His compositional style represents a distinctively spare form of tonal neo-Romanticism. Paganini and Jean Sibelius are acknowledged influences.Music as symbol and object The music in the film is important in three different ways. First it functions conventionally as a score which complements the visual image at certain times in order to confirm and emphasise the emotional impact of a scene. However, this basic function is superseded by its importance as the object of Julie’s quest and by its symbolic function. As an object – that which Julie must enable to be performed – the ‘Song for the Unification of Europe’ has to be ‘presented’ to the audience as something in its own right artistically. Therefore something odd is required – we must ‘hear’ the music as Julie remembers it and ‘finishes’ it. (The narrative intrigues us to the extent to which Julie is indeed the original composer of her husband’s music.) The music that we hear on the soundtrack is diegetic in the sense that it belongs to the fictional world of the film, but we rarely see the music being performed (i.e. confirming its diegetic status). Instead we hear what is inside Julie’s head – or her memory. We will want to think about the scene, for instance, when the camera offers us close-ups of the notes as each is played and Julie traces along the score with her finger. We could argue that the music becomes a character in the film’s narrative, like a child which is finally born in the closing scenes of the film. There are several film genres in which something similar might happen.

Juliette Binoche seems like perfect casting for the role of Julie. Not only beautiful and serene, but also clearly intelligent and strong, she posses all the qualities to be able to work with the script and make credible her character in the narrative. Only in her late twenties when she made the film, ‘la Binoche’ was already being discussed as a star after her roles in The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1988), Wuthering Heights (1992) and Les amants du Pont Neuf (1991). Watching Bleu again now, we are more aware of how she has come to dominate the interesting roles provided by directors such as Hou Hsiao-hsien (e.g. Le voyage du ballon rouge (France-Taiwan 2007), Abbas Kiarostami (i.e. Certified Copy (France-Italy-Belgium-Iran, 2010) and more recently Claire Denis (Let the Sunshine In (France-Belgium 2017). In Bleu, what her performance conveys is a stillness, a strength and a minimalism – all of which gradually ‘melt’ away as she becomes able to develop emotional relationships again. Re-watching the film again in 2025 is to be forcibly reminded of Binoche’s performance and this time I was much more aware of the ‘bob’, that hair style that seems so iconic across all of cinema, but especially French cinema and links Binoche in this role to Anna Karina in Vivre sa vie and Louise Brooks in Pabst’s Pandora’s Box from Weimar Germany. Juliette Binoche is a truly international star actor who has worked with directors from across the world. She embodies the optimism of a new Europe presented through Kieslowski’s vision in Three Colours Blue – if only we could be optimistic now in the face of Trump!

Resources

Wikipedia has a useful general page on the film with some links: Three Colours Blue

Preisner’s own website has samples of his music:

http://www.preisner.com/

Other Preisner sites are listed as links on

www.musicolog.com/preisner.asp

Kieślowski discusses the trilogy briefly in this book, first published in 1993:

Danusia Stock (ed) (1995) Kieślowski on Kieślowski, London: Faber and Faber

Juliette Binoche seems like perfect casting for the role of Julie. Not only beautiful and serene, but also clearly intelligent and strong, she posses all the qualities to be able to work with the script and make credible her character in the narrative. Only in her late twenties when she made the film, ‘la Binoche’ was already being discussed as a star after her roles in The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1988), Wuthering Heights (1992) and Les amants du Pont Neuf (1991). Watching Bleu again now, we are more aware of how she has come to dominate the interesting roles provided by directors such as Hou Hsiao-hsien (e.g. Le voyage du ballon rouge (France-Taiwan 2007), Abbas Kiarostami (i.e. Certified Copy (France-Italy-Belgium-Iran, 2010) and more recently Claire Denis (Let the Sunshine In (France-Belgium 2017). In Bleu, what her performance conveys is a stillness, a strength and a minimalism – all of which gradually ‘melt’ away as she becomes able to develop emotional relationships again. Re-watching the film again in 2025 is to be forcibly reminded of Binoche’s performance and this time I was much more aware of the ‘bob’, that hair style that seems so iconic across all of cinema, but especially French cinema and links Binoche in this role to Anna Karina in Vivre sa vie and Louise Brooks in Pabst’s Pandora’s Box from Weimar Germany. Juliette Binoche is a truly international star actor who has worked with directors from across the world. She embodies the optimism of a new Europe presented through Kieslowski’s vision in Three Colours Blue – if only we could be optimistic now in the face of Trump!

Resources

Wikipedia has a useful general page on the film with some links: Three Colours Blue

Preisner’s own website has samples of his music:

http://www.preisner.com/

Other Preisner sites are listed as links on

www.musicolog.com/preisner.asp

Kieślowski discusses the trilogy briefly in this book, first published in 1993:

Danusia Stock (ed) (1995) Kieślowski on Kieślowski, London: Faber and Faber

I came into Three Colours Blue as a fan already of Zbigniew Preisner’s music which I first encountered in The Double Life Of Veronique where it was almost as prominent. I started with a cassette of Veronique and later followed up with a CD exclusively devoted to the various collaborations between Kieslowski and Preisner. I liked the Three Colours trilogy in general, but guess I preferred Red if for no better reason than it features the sublime Irene Jacob, also of Veronique. At the time, the fruitful collaborations of Kieslowski and Preisner put me in mind of the long running Peter Greenaway / Michael Nyman combo. How quickly Greenaway’s films fell off when they parted company, though looking back now it seems to me he was generally over-praised. Certainly a repeat viewing of Drowning By Numbers a while ago found it nearly unwatchable.

LikeLike

Yes, I like The Double Life of Véronique as well. I could never really understand the interest in Peter Greenaway so I didn’t get into Muchael Nyman until The Piano (1993), Gattaca (1997) and the films he scored for Michael Winterbottom. Wonderland (1999) remains one of my favourite films (and music scores).

LikeLike

yes. Wonderland. The assembled cast for that was astonishing looking back : John Simm, Ian Hart, Shirley Henderson and a great performance from Gina Mckee breaking down on the top deck of the bus. Yet another Nyman soundtrack I own.

If I still have any grudging respect for Greenaway, The Cook, The Thief etc was one where he really did excel.

LikeLike