Signature is a distributor that has picked up several interesting films for the UK in the last few years. On the one hand, this is a good thing as it offers a means to get to see the films, but it is also frustrating since the company seems intent on getting the films onto streamers as quickly as possible. This in turn means that the films don’t stay long in cinemas. The New Boy was screened at Cannes in 2023 but didn’t appear on UK screens until 15 March 2024. It opened on 61 screens but made only £257 per screen on average over its first weekend, so I suspect that it didn’t last long. I’m assuming most of those screenings were in multiplexes and the figures don’t surprise me. I wonder if the release would have been more successful with fewer prints in specialised cinemas which might have promoted the film more carefully?

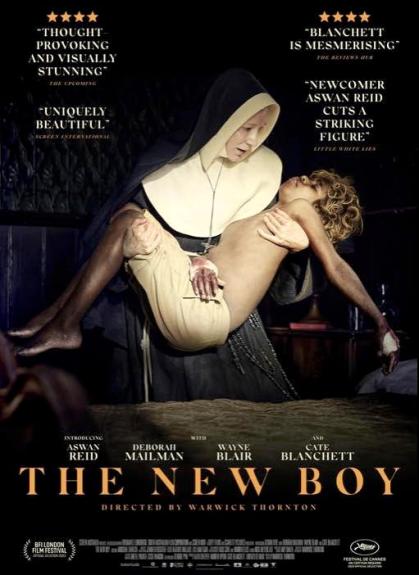

Warwick Thornton is one of the few Indigenous Australian filmmakers with a high reputation in international cinema (alongside Ivan Sen) and I was very impressed by his earlier films, Samson and Delilah (Australia 2009) and Sweet Country (Australia 2017). Thornton is a cinematographer as well as a director and for The New Boy he wrote the script as well (as he had done for Samson and Delilah), basing it partly on aspects of his own experience. The film has only a small cast of four main actors in speaking parts. Two of the four are Deborah Mailman and Wayne Blair, as an actor and the director respectively on The Sapphires (Australia 2012), a film about a ‘girl-group’ of Indigenous singers entertaining African-American troops during the Vietnam War. Thornton was the cinematographer on this film. All three of the films I’ve referenced in this paragraph included familiar genre elements in their stories and this proved on the one hand beneficial in getting them a wider release, but also partly obscured the distinctive elements of Indigenous Australian culture in the narratives. The New Boy is slightly different in this respect and its fourth main actor is the amazing Aswan Reid making his début as the titular character. He carries the narrative remarkably.

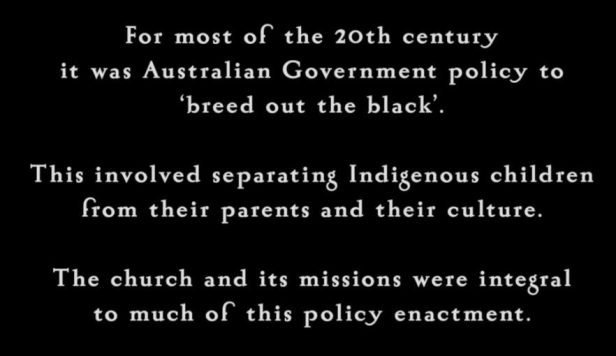

The film opens with a title card briefly explaining the Australian government policy in the 20th century of attempting to forcibly assimilate Indigenous children into White Australian culture – but it does this more forcibly and directly (see the text above). It also explains that the church was one of the main agencies involved in this process. Immediately following the text the narrative opens with a young (9-10 year-old?) Indigenous boy being finally overpowered by two police officers in open country. He is transported by horse, train and motor vehicle from the edge of the ‘Great Sandy Desert’ in North East Australia to an orphanage several days travel away run by the Benedictine Order (the film was mainly shot in South Australia). We learn this from a voiceover reading of a letter. Otherwise we learn little except that this is wartime, presumably in the early 1940s. The boy doesn’t have a name and appears to have no connection to other Indigenous groups in the region in which he was found. It was often the practice to take children like this hundreds of miles across Australia, as we learn in the film Rabbit-Proof Fence (Australia 2002).

This is one of those films that divides audiences. On IMDb we can see ‘user comments’ that range from ‘outstanding’ to ‘garbage!’ with many of the professional critics in the middle. Before I attempt to untangle my own thoughts I should note that the Blu-ray and the cinema print in the UK run for 96 minutes while the Australian original print and that shown at Cannes ran 116 minutes. The cuts were made by Thornton himself so it’s legitimate to comment on the shorter version but some of the comments by critics about its pacing may refer to the original version. Cutting twenty minutes would completely change most films. For my part, the ending of the film as it is now does seem a little abrupt and truncated but that doesn’t detract from the powerful statement Thornton is making.

The ‘new boy’ finds himself in what is a very small orphanage with no more than a handful of boys, some of whom are Indigenous and the others are white or perhaps ‘passing for white’. The sister in charge is Sister Eileen played by Cate Blanchett and the only other adults are a sister known as ‘Mum’ (Deborah Mailman) and the farm-hand/handyman George (Wayne Blair). We quickly learn that there was originally a monk Dom Peter who was in charge and we assume that he died but his death was not reported and Sister Eileen pretends he is still alive. We suspect that she is worried her drinks habit will be discovered by any investigation. The orphanage farm survives by harvesting a grain crop and other smaller food production activities.

Thornton’s intention is to show rather than tell us about the process of forced assimilation. The ‘new boy’ arrives as a ‘wild child’ and initially Sister Eileen makes no attempt to change him. He remains barefoot, sleeps under his bed and doesn’t wear the simple uniform of shorts and shirt like the other boys. But he is intelligent and ‘gifted’. Thornton provides him with a visual signifier of his power of healing – a light source that orbits him like a ball of fireflies when he summons it. This seems to alienate some audiences expecting a social realist account of the boy’s ‘schooling’. But the spiritual energy that the boy feels is also his possible weakness in that he finds himself intrigued by the rituals of the church, especially when a wagon arrives bringing a large wooden crucifix with the figure of Christ hanging from it. I don’t want to spoil the narrative but this fascination will eventually allow Sister Eileen to strip the boy of his own sense of identity. The film works for me because its story is told primarily through Thornton’s terrific cinematography and the extraordinary performance by Aswan Reid as the ‘new boy’. A great deal of comment has been made about Cate Blanchett’s performance. She is accused of overacting and using the film to promote herself, both of which I think are worthless charges. The problem is that many audiences will respond to her presence as their main way into the film. Her presence was no doubt important in getting the film made and then distributed but the story is about the boy and the system that attempts, quite literally, to take away his identity. In this respect Blanchett’s Sister Eileen is just like Kenneth Branagh’s ‘Protector of Indigenous children’ in Rabbit-Proof Fence. The history Australian government policy towards Indigenous Australians is shocking and unfortunately needs to be presented on screen over and over until audiences recognise what happened. This story is Warwick Thornton’s inspired by his experiences growing up in similar circumstances in the 1980s and I admire him for telling it in the way he does.

The issue for many audiences is likely to be that the narrative does not have a conventional ‘arc’ and it ends at a point of defeat for the ‘hero’. I worry that perhaps audiences will not recognise how terrible is his fate. The boy is not treated ‘badly’ in the conventional sense – he isn’t beaten or ritually punished. But having his native spirituality removed and replaced is worse. This is a wound that won’t heal and will remain with him throughout his life. It is this that I feel needs to be understood. In 2023 the Australian electorate voted against a proposition to create ‘a Voice’ for Indigenous Australians, something that went beyond ‘equal rights’ and would have given them access to reserved seats in the legislature as well as a body which would have the power to take the concerns of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and present them directly to both the legislature and executive of the Australian government. In an article in 2024 exploring why the vote went against the proposition (when early polling suggested a clear majority) reference is made to the comments of Andrew Gunstone, associate deputy vice-chancellor for reconciliation at Federation University:

In Reflections on the Voice: During and After the Campaign, he reports that his surveys in 2005, 2010, 2015 and 2020 showed (in his summary) “how racist many non-Indigenous people are towards Indigenous issues as well as how ignorant they are and also how lacking they are in a sophisticated understanding of what equality is.”

While the whole question of the Voice campaign and the analysis of its failure is complex, this observation does point towards why films like The New Boy are important and why they need to be seen and discussed as widely as possible. The New Boy is available on several streamers including Apple, Amazon, BFI Player and Sky as well as on the bare-bones Blu-ray from Signature.