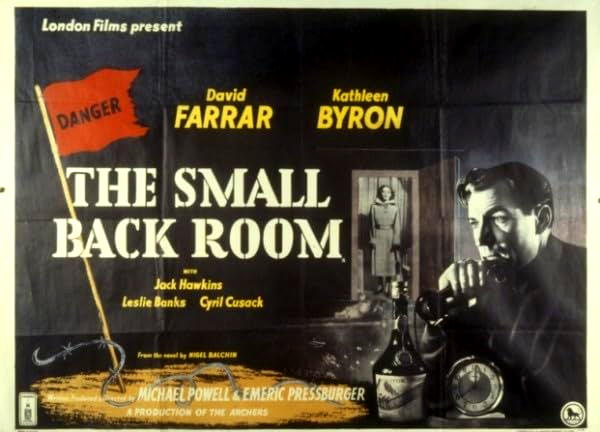

I couldn’t allow this year’s BFI celebrations of the work of Powell & Pressburger and the release of Made in England: The Films of Powell and Pressburger to go by without discussing one of the best films from The Archers and one of my personal favourites but also one that has not received the full attention it deserves. The Small Back Room (known in the US as The Hour of Glory, not perhaps the best title for this story) has three major attractions for me. It stars David Farrar and Kathleen Byron in a difficult relationship. It is an adaptation from a novel by the incomparable Nigel Balchin and its stylistic devices include some highly expressionist scenes in what is arguably a British film noir. It also has some terrific location scenes, including one on Chesil Beach. All of the Archers gang are involved in the film’s production apart from Alfred Junge who had left after Black Narcissus (1947) but by now The Archers had left the embrace of the Rank organisation – an embrace sometimes warm but also suffocating and restrictive – and had moved back to Alexander Korda and his London Films. Brian Easdale was the music composer and it sounds like the theremin, introduced in Hollywood films earlier in the 1940s, was used in the expressionist sequence. Ted Heath’s band appears in the nightclub scene in what was the first period of fame for the band. Freddie Francis, a future major DoP and later director of low-budget features was the camera operator for Chris Challis and would go on to work on six of the Archers’ productions.

The narrative focuses on Sammy Rice (David Farrar) and his partner Susan (Kathleen Byron). They seem to live in adjoining flats. Sammy is not easy to live with. He’s a scientific expert assigned to Professor Mair’s section. His aluminium lower leg gives him a lot of ‘gyp’ which he tries to relieve with pills and alcohol. The alcohol is starting to make him dependent and he suffers from withdrawal symptoms if he doesn’t get enough. But this is 1943 and the Germans are developing new booby trap bombs to be dropped on various UK targets, including civilian districts. Sammy is needed to figure out how to defuse them.

Nigel Balchin was a scientist before he became a novelist and scriptwriter and the 1940s was the peak period of his novel-writing career. He had studied Natural Sciences at Cambridge and worked as a psychologist in the food industry during the early 1930s. He was a civil servant in the Ministry of Food in wartime. Eventually he moved to the Army Council as Deputy Scientific Advisor and these experiences were the basis for the semi-autobiographical aspects of The Small Back Room – the novel was published in 1943. It must have been a slightly different task for P&P and especially for Pressburger, to adapt the novel. They had adapted other novels, most recently Rumer Godden’s Black Narcissus, but Balchin was not just a celebrated living author but already himself a scriptwriter, adapting Howard Spring’s Fame is the Spur and his own novel, Mine Own Executioner (both 1947). I’m sure I have the original novel of The Small Back Room somewhere and I may have read it, but what I do know is that the film adaptation encouraged me to seek out other Balchin novels (and films). The crucial point, I think, is that Balchin understood the ‘back-room boys’ whose role was important in the Second World War. In other films, the scientists became ‘boffins’, either eccentric or in some cases disturbing, but Balchin knew what he was writing about. Part of Sammy’s problem, well brought out in Nick James’ Criterion essay on the film, is that he has to work with the civil servants who don’t know, or care, about the War from the perspective of the soldiers or the scientists trying to help them.

The film introduces us to Captain Stuart (Michael Gough). Prof. Mair tells him Sammy Rice is the man he wants. Susan (Kathleen Byron), the secretary to the Section Head ‘R. B. Waring’ (Jack Hawkins) then helps Stuart find Sammy in his local boozer, where the barman Knucksie (Sid James, a regular bit-part player in British films around this period) is trying to steer Sammy away from drinking whisky. Stuart accompanies Susan and Sammy back to their adjoining flats where he tells them about the suspected booby trapped bombs being dropped by the Germans. All of this takes place in the blackout of Central London in Spring 1943 where there are military men and government officials of all the Allied powers, both in the offices and the pub.

There are three scenes which take us away from the London streets, Sammy and Susan’s rooms, pubs and the tube. One takes Sammy to Bala in North Wales and the final climactic sequence is on Chesil Beach. The third scene is a representation of Sammy’s desperate longing to escape from the pain of his leg in the comforting arms of a bottle of ‘Highland Clan’ whisky. This is one of Michael Powell’s most wonderful expressionist moments but of course some of the 1940s critics picked it out as their reason to reject the film. Monthly Film Bulletin‘s anonymous reviewer in March 1949 refers to this sequence as a ‘lapse’ in the otherwise efficiently directed film:

The lapse which it is most hard to forgive is that into surrealistic camerawork illustrating Rice’s internal struggle with himself when, with his morale at its lowest ebb, he thirsts to open a bottle of whisky.

The reviewer doesn’t like this sequence, which is fair enough, but why does it become a ‘lapse’? The clue might be the low ‘morale’. Presumably his lip isn’t stiff enough. Perhaps if the reviewer considers that Sammy is in pain and possibly addicted to the ‘escape’ from pain that he struggles with, the reviewer could be more charitable. The reviewer could write that they don’t like the sequence without damning it as a ‘lapse’. You might think I’m making too much of this, but these kinds of criticism eventually propelled The Archers to the outer limits, away from the glories of ‘quality cinema’ as seen in the films of David Lean and Carol Reed. It would be 30 years before The Archers were afforded their place in the pantheon and their films would be re-screened in the late 1970s and restored from the early 1980s onwards.

The bomb de-fusing sequence on Chesil Beach did, however receive universal praise. It’s a long sequence, around 18 minutes with several effective features. Visually and aurally the biggest plus for the location in terms of creating tension is the bed of shingle, which means holding the booby-trapped device stable is very difficult, as is Sammy’s position – he can’t afford to slip while trying to dismantle the device. There is also the open-ness of the landscape. It must be windy and chilly on an early morning in March on the beach but Sammy is sweating with the tension. It’s an unusual situation for a character in a P&P film. Renée Asherson as the ATS Corporal who took down the radio link message from Capt. Stuart while he was dismantling the first device is interesting casting. She was at the time a well-known stage actor and the partner of Robert Donat but she had only been in films from 1945. It’s a small role but an important one in that Sammy speaks to her quite calmly and considerately given the situation and we might wonder if he is thinking about Sue.

The Small Back Room is a good title, albeit taken directly from the Balchin novel. It has a dual meaning relating to Sammy and Susan’s rooms and to the War Department office from which Sammy plies his trade as ‘backroom boy’. In both cases there is a sense that Sammy’s world is in the shadows rather than ‘out in the open’ – which makes the extended Chesil Beach scene even more powerful by contrast. Overall the script sticks fairly closely to the novel but Asherson’s character is an invention for the film and the ending is not the same, although Pressburger used some of Sammy’s thoughts for an earlier scene. The novel ending is different in that Sammy feels more of a failure because of the struggle he had dealing with the device and when he gets back to London he thinks about meeting Sue but then the narrative stops abruptly. The film has, by comparison a ‘happier’ ending. I confess that the film’s ending which seems to suggest a future for Sammy and Sue is, in this case, the more acceptable choice, especially because of memories of the ending of Black Narcissus. This is a very different film to either the wartime productions or the post-war Technicolor melodramas, but it’s still an essential Archers film and not to be missed.

Lots of info and original research there and agree with sentiments about the value of the film. Often marginalised as more of a Powell for assumed docu-drama leanings rather than a further P and P imagining, but this has the same intense focus on the central character’s emotional state as Wendy Hiller’s in I Know Where I’m Going, all because of a (potential) partner who knows better. The DT’s scene is as expressionist as anything else the pair made. And a worthy mention of the film’s noir qualities. Never thought it like that, but when you name it, it’s obvious. Thanks. Great film.

LikeLike