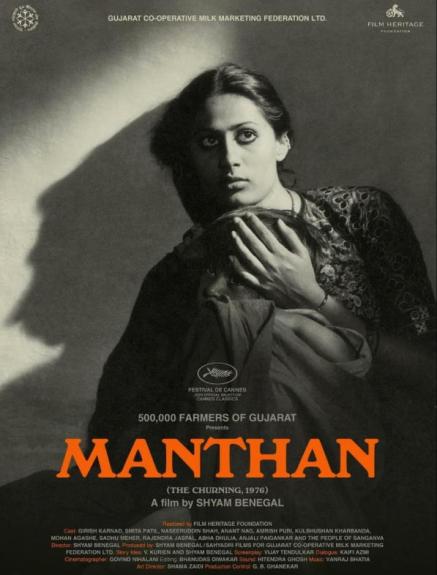

There is currently a revival of interest in the ‘Parallel Cinema’ of India between the late 1960s and the late 1990s, partly as the result of the hard work of Dr. Omar Ahmed, whose book on this important period of independent filmmaking across India will be published in Spring next year. This month sees the Leeds International Film Festival showcasing one of the leading actors of Parallel Cinema, Smita Patil, whose star burned bright before her tragic death aged only 31 in December 1986. In her short acting career of just 12 years, Patil appeared in 80 films, included many of the most important parallel films. LIFF is showing five of Smita Patil’s performances, using digitally restored prints in a festival section titled ‘Smita Patil: Spice and Fire’. Omar Ahmed has acted as advisor and has introduced some of the screenings. I’m hoping to get to at least two of the screenings but I realised that I had already got one of the titles recorded from a Channel 4 screening a couple of years ago and so I watched that first.

The Churning was one of Smita Patil’s early films in which she has a small but crucially important part. The title of the film points immediately to a pun based on the fundamental process of the dairy industry in rural India and the first title card on the film announces that it was funded by 500,000 dairy farmers in Gujarat under the banner of the Gujarat Milk Co-op Marketing Federation. The narrative is about setting up a Milk Co-operative but if you think that means a worthy docudrama, think again. The milk gets churned but so do the lives and the relationships of the villagers and the team from the city who come to introduce the idea of the co-op. The film was written and directed by Shyam Benegal with Vijay Tendulkar and Samik Banerjee. Benegal has a slightly different background to the other major figures of Parallel Cinema in that he didn’t attend FTII (Film and Television Institute of India), though he did teach there later and instead began a career in advertising as a copywriter in the mid 1950s and moved on to making documentaries. He was also more able than most other filmmakers to find ways of raising money for his films, as this production demonstrates. Nevertheless his ideas and the narrative content of his films make him an important part of the development of parallel film. Born in December 1934 Benegal has been the most prolific of all the filmmakers associated with Parallel cinema. I’m not going to try to explain Indian Parallel Cinema at this point but I did try several years ago on this blog. During the 1980s when I first became interested in exploring these films, we used three terms to describe films made from the late 1960s onwards which took a different approach to the commercial popular cinemas of India. Some of the more experimental films were referred to as ‘New Cinema’, some of those closer to commercial films were sometimes termed ‘Middle Cinema’. Parallel Cinema was a more distinctive term to describe filmmaking in several parts of India in a variety of languages and arguably developed the most currency.

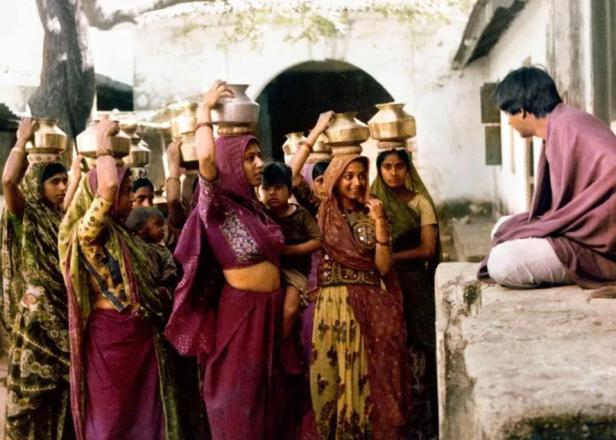

The narrative of The Churning is conventional in many ways. A small group of youngish men ‘from the city’ arrive in rural Gujarat with the intention of trying to persuade local farmers to form a co-operative. The city group is led by a veterinary surgeon Dr. Rao (Girish Karnad), a forceful and direct character committed to the project. He discovers that the team has been sent to a district in which the large landowner Mishra (Amrish Puri) runs a dairy which receives the milk produced by the small farmers who might own only one or two buffalo each. Mishra pays a low rate for their milk and as a consequence farmers water down the milk which lowers the overall fat content. Rao’s aim is to attract the farmers and to sample their milk, paying higher rates for higher fat content. But he soon realises that this will not be an easy task. Mishra has his finger in several pies and the politics of the district are complex. The community is divided along caste lines and many of the small farmers are Harijans seen as the lowest caste. The village headman (Kulbhushan Kharbanda) enforces the caste divisions and among the Harijans, Bhola (Naseeruddin Shah) is a strong and independent, but rather hot-headed character. Rao has a difficult job. He must attract the small farmers, including the Harijans, to a co-op in which there is no discrimination along caste lines. All members will be equal and they must agree to form a co-operative and elect a chairman. The co-op will only work if it includes most of the local farmers as members. Rao can see that the three characters described above all have reasons to resist the imposition of a co-op and within the ranks of his own team he will also struggle to maintain unity. Bindu (Smita Patil) is one of the Harijans. Her husband is away from home when Rao and his team first arrive. Because she is another forceful character, Rao meets her and tries to persuade her to to have her milk sampled and to consider joining a new co-op. His intentions seem good but there is danger in his approach, especially when his young wife Shanta (Abha Dhulia) arrives from the city and is not impressed with the local accommodation.

Benegal is deft in developing the battle of wills in the village. Rao’s first move is dismissing one of the men who came with him for getting too close to Mishra. He’s also perhaps a little naive in not recognising the threat his actions pose to Mishra, the headman and Bhola. Violence is never far away as he discovers when he shows a film about forming a co-op to the villagers one evening. To be viable, the co-op needs most of the villagers to submit and Mishra with his contacts and his bully boys has several ideas about how to divide the farmers. The ending of the film is intriguing since Benegal must find a way to allow the co-op to be formed but also to expose the underlying struggles. Caste does still matter in India today and Gujarat is the base of the right-wing Hindu nationalism which brought Modi into power.

The restored print looked great on my TV set, especially in terms of the bright colours achieved by Govind Nihalani, another major figure of Parallel Cinema, both as cinematographer and director. I’m not sure when I recorded it and since the print showing in Leeds is described as a 4K restoration, it should look very good on the big screen. As well as Smita Patil, the other actors in leading roles would all become familiar actors in both parallel and more mainstream films. I’m hoping now to write something about the two LIFF screenings I have managed to get to and to look for more prints in my archive.