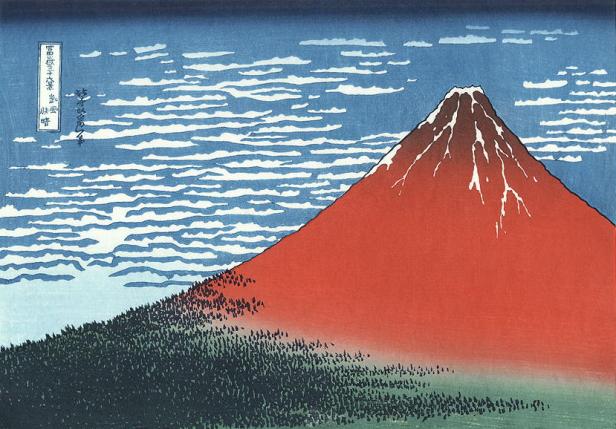

I have good memories of Kirschblüten from an evening class I ran with Rona Murray back in 2010 and I have been revisiting the film for another event in which I’m looking at films made in Japan telling Japanese stories. This film fits that rubric in an unusual way. Rudi and Trudi are a German couple in their sixties living in a small town in Bavaria. The couple are played by two legendary German actors, Elmar Wepper as Rudi and Hannelore Elsner as Trudi. Rudi travels to his work in local government each day by train but he is close to retirement. Trudi doesn’t appear to have a job but she has looked after three children all now grown-up and living away. She visits her local surgery to be told that Rudi has a terminal illness and the two doctors who speak to her say they weren’t sure how he would react to the news so they are telling her first. They think the couple should have a holiday – an ‘adventure’ they suggest. Writer-director Doris Dörrie has already teased us when during the credits we are shown woodblock-type images of Mt. Fuji with Trudi’s voiceover accompanying the last image. She tells us that she had always wanted to visit Japan with Rudi to see Mt. Fuji and the cherry blossom and she can’t imagine visiting without him. But unaware of the diagnosis he doesn’t want to go anywhere until she persuades him to visit their son and daughter in Berlin. Rudi has turned down the idea of visiting their other son in Tokyo.

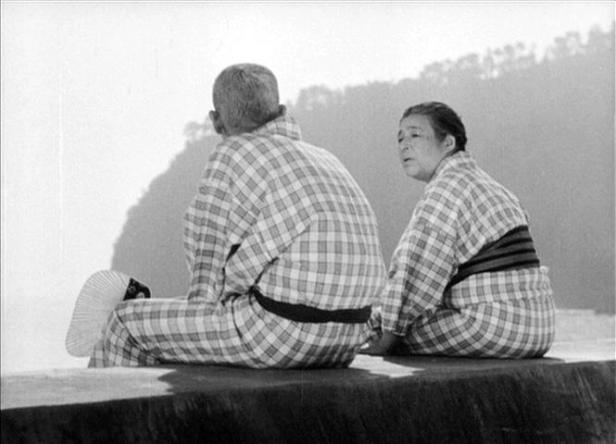

But just less than a third of the way into the film, Trudi dies in her sleep. If you have seen Ozu Yasujiro’s Tokyo Story (Japan 1953), you will probably have worked out that the first part of this film narrative borrows much of its plotline from Ozu’s film. The parents travel from their small town to visit their grown-up children in Berlin who lead busy lives and can’t really cope with their parents’ sudden arrival. The parents go off to a resort on the Baltic coast for what turn out to be their last moments together. Just as in the Ozu narrative, there is another son who in this case flies in from Tokyo for the funeral. At this point the clues begin to come together and we realise what Trudi’s almost obsessive love of aspects of Japanese culture meant to her. Rudi decides he must go to Tokyo and in some way live out Trudi’s dream in honour of her. I don’t want to spoil the rest of the narrative too much just in case you manage to find a copy of the film but I found the final section of the film very moving. Below I explore aspects of Trudi’s dream.

Doris Dörrie became fascinated by Japan herself when her first film as director Mitten ins Herz (1983) was shown at the Tokyo Film Festival and she was invited to discuss it. She has subsequently made two more films at least partially set in Japan (including a form of sequel to Kirschblüten) and some of her first impressions in 1983 influenced the production of Kirschblüten in 2007. One of her later films prompted by the nuclear disaster at Fukushima is covered on this blog – Greetings from Fukushima (Germany-Japan 2016). Dörrie has been an important director in Germany in both cinema films and television since the early 1980s. But she is not an art film director even though she has been recognised by many German and International Film Festivals. She commits the sin of making comedies and other forms of popular films, often about relationships and particularly about gender. Her most successful film commercially is Männe (Men, 1985) and Sabine Hake in German National Cinema (Routledge 2002) suggests that Dörrie is the most important German director to emerge in the 1980s. But ‘foreign language comedies’ tend not to travel well because of both misunderstandings and prejudice, often from leading critics. It has been very difficult to see her films in the UK apart from in festivals or on the release of a handful of films like Kirschblüten on disc. Some reviews of Kirschblüten in the US recognised how well it worked but still tagged it as ‘light’. Here’s an example:

. . . Doris Dörrie, who started out just dandy with the outrageous 1984 comedy Men and has settled for charming neo-hippie fripperies pretty much ever since. The best I can say for Cherry Blossoms is that it’s made with love; the worst, that it’s been a big hit in Germany. Yearning for Ozu, Dörrie stops off at cute, and parks. (Ella Taylor, Village Voice, January 2009.)

I would have thought that a film that can engage audiences and move them while also introducing them to another culture would be heralded. Since foreign language films are seen as only for ‘specialised’ audiences reviews like this can deter distributors. Fortunately, Doris Dörrie, one of the most important female directors in Europe is still going. Her 2022 film Freibad (The Pool) was released only in German-speaking territories. Just Watch UK knows who Doris Dörrie is but none of her titles seem to be available to stream. I found the film online on a good print without subtitles which I then found separately.

Why does the film work so well? Dörrie knows how Japan feels to someone visiting for the first time and also enough about Japanese culture to know how to present the country without any of the mistakes that sometimes trip up visiting filmmakers. Trudi’s dream nurtured over many years has three principal elements. First is Hanami, the traditional celebration of the emergence of cherry blossom that occurs first in the southern part of the Japanese archipelago and gradually moves up the country as the blossoms open. The celebration prompts picnics in suitable places close to the cherry trees with friends, office colleagues or family. When Rudi joins a picnic with his son he gets a real introduction to Japan and help in fulfilling Trudi’s dream. Trudi learned all about the modern dance style of Butoh, an avant garde dance form that first developed in the late 1950s featuring dancers in:

“white body paint, slow and arrhythmic body contortions expressing a confluence of anguish and rapture, and a dedication to form and improvisation that is deeply connected to the nature of being. (See this website for more explanation.)

Rudi has the idea that he needs to combine Butoh with Trudi’s reverence for the views of Mt. Fuji which he discovered going through his wife’s things. He needs to find someone who will help him find a place where Mt. Fuji can be quite clearly seen and there create something that represents Butoh. For someone who has not had a ‘creative life’ in terms of dance that is a tall order, especially given the circumstances. But this is the kind of film narrative where all kinds of things are possible. Here is the sequence where Rudi finds the person who can help him. (The dialogue is in English which the German man and Japanese woman must use to communicate.) The film was shot on HD Video by Hanno Lentz and there is an interesting music soundtrack that includes two tracks by Ryuichi Sakamoto.