For his third feature John Sayles took the plunge and accepted a project associated with a major studio, Paramount. He discovered the hard way why he should have been more careful. The project had a good script and two good producers. The original idea and script were by Amy Robinson and she was also the producer alongside the actor Griffin Dunne. Robinson had first appeared as an actor in Mean Streets, the first studio picture by Martin Scorsese in 1973. She didn’t like the scripts she got later on so she wrote a script for a form of youth picture or ‘coming of age’ story based on her own experiences growing up in Trenton, New Jersey and then attending Sarah Lawrence College in New York. She and Griffin Dunne became a production partnership and they made their first film in 1979 with Joan Micklin Silver. Chilly Scenes of Winter (aka Head Over Heels) starred John Heard and Mary Beth Hurt and was released through United Artists. Micklin Silver wrote the film herself and she was one of the relatively few women directing features in Hollywood in the 1970s. When Robinson and Dunne approached Sayles to make Baby It’s You it seemed like an attractive opportunity.

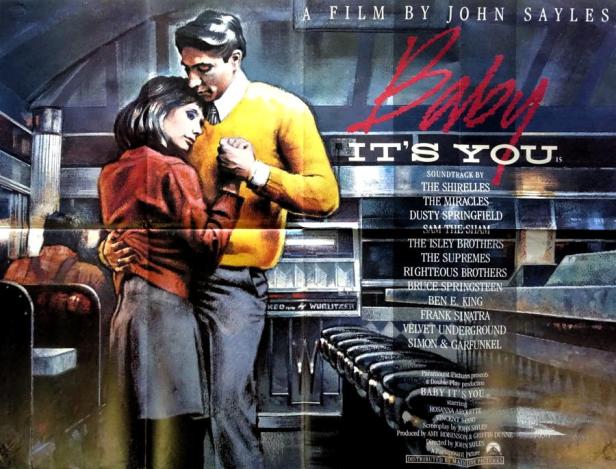

Sayles and his partner Maggie Renzi took this on as their third feature. They were already aware of some of the difficulties they might face with a studio involved as their second film, Lianna (1983), was distributed by United Artists Classics division, which was discontinued before the film had properly hit cinemas. Maggie Renzi did not become directly involved in this next production. Sayles was now ‘hot’ with his first two films having been well received critically and the screenplays he had written for producers like Roger Corman had led to successful releases. Paramount agreed to ‘pick up’ Baby It’s You as a negative. This meant that the union rates were a little lower than for a wholly-produced studio film. In effect, the studio promised to buy the film, enabling Robinson and Dunne to get a loan to make the film which they could redeem when Paramount paid up. The film would have a budget of $3 million. The positives for Sayles in the arrangement included a lack of studio interference on the shoot and the chance to use a soundtrack peppered with pop and soul/R&B hits. This was important because Robinson and Sayles, who worked together on the shooting script, agreed that high school kids in the sixties identified themselves with particular types of popular music. Sayles had a budget of $300,000 for music rights – a sum equivalent to the whole production budget of Lianna. A decade earlier George Lucas had a major success with American Graffiti (US 1973) which generated a very successful soundtrack album of late 1950s/early 1960s songs. The potential for a Baby It’s You album is hinted at in the poster above. The other pluses were a 43 day shoot and the services of Michael Ballhaus as DoP. One of the major figures of the New German Cinema, known especially for his work with Rainer Werner Fassbinder and now in America full-time, Ballhaus was an ideal working partner for Sayles. The down side of the deal was that the studio could take the finished film and do as they wished with it. Since it was for them a relatively low budget project, they could simply not bother distributing it properly if they didn’t like it. In retrospect this sounds like a deal that Sayles shouldn’t have gone for, but it still produced a film worth watching and one arguably much better than Paramount deserved.

Sayles liked Robinson’s project because he recognised the high school experience in the mid-1960s from his own schooling at that time, but what really intrigued him was that the story continued into the first couple of years post-school and into the college experience of the female character. (He himself had experienced a difficult time as a student at Williams College, a similarly prestigious school as Sarah Lawrence.) For him the film was a social drama about two young people from different social backgrounds. Unfortunately, what Paramount wanted was yet another variation on a popular high school/teen comedy. This was the period of Fast Times at Ridgemont High and Valley Girl (both 1983). But these were contemporary-set films located in Southern California. Baby It’s You is set in New Jersey in the 1960s. Amy Robinson recognised a tension between her own motivation for the script – to explore a romance – and Sayles’ focus on social class but this wasn’t the major issue.

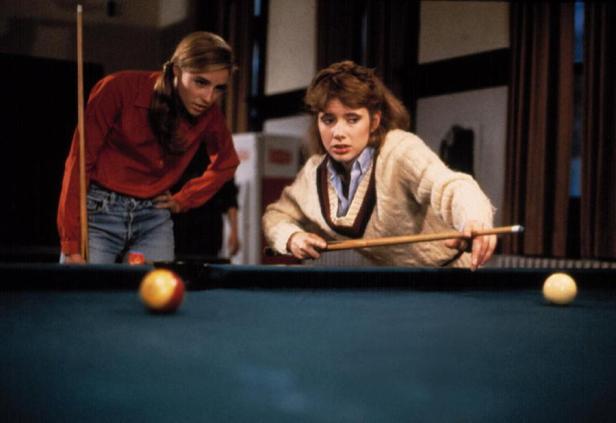

Rosanna Arquette was cast as Jill Rosen from a middle-class Jewish family. She was 21 when shooting began but she is convincing as an 18 year-old high schooler as well as a 20 year-old in college. She had significant experience gained from television work on series and TV movies as well as small parts in cinema features. I think she is very good as Jill but she wasn’t as ‘glamorous’ as Paramount expected. She would get much more exposure when she starred opposite Madonna in Desperately Seeking Susan (1985) and then in After Hours opposite Griffin Dunne in Dunne and Robinson’s film directed by Martin Scorsese (also 1985). Vincent Spano as ‘the Sheik’ had less experience than Arquette and he is three years younger. He did, however, have a role in a key ‘youth picture’, Jonathan Kaplan’s Over the Edge in 1979, another film that struggled for release in both the the US and the UK, because of violent behaviour by younger teens. He would appear again for Sayles in City of Hope (1991).

Baby It’s You opens with ‘Wooly Bully’ by Sam the Sham and the Pharoahs. The song plays under the opening credits (violet text against a black background) until the classroom doors burst open on a high school corridor. We meet Jill with a gaggle of her friends and she is somewhat taken aback when Sheik sweeps past the girls and then turns to look at Jill. He seems a foot taller than anyone else and he’s dressed in a sharp dark suit rather than the usual school casual clothes. We learn from a whispered aside that he has just been transferred to the school from a Catholic boys school. For the first half of the narrative, Sheik will pursue Jill during the school day. We never see him in class and he seems to just wander through the school, even entering Jill’s class during a lesson and turning up in the school canteen in the wrong sitting to try to engage Jill in conversation. Jill is a bright young woman, clearly heading for higher things and she is one of the leading lights of the school drama club, auditioning for the lead role in the next play. As one of her less privileged friends complains, Jill seems to be handed everything on her plate. But she isn’t spoilt or ‘stuck up’ and she’s secretly flattered by Sheik’s attention. Eventually she will go out with him, but she doesn’t want to take it further.

Sayles is keen to explore the home life of both Jill and Sheik (known as ‘Albert’ at home). Jill’s father is a doctor and her parents are ‘liberal’ with high expectations. Sheik’s parents are a doting mother and a ‘rough and ready’ father who exchanges angry insults with his son. It’s an Italian working-class home and Sheik is proud of his Italian parentage. The school narrative is conventional with many of the usual drama highlights being built around prom night, exchanges in the canteen, confrontations on the street, cinema trips, first visits to a neighbourhood bar, showing off in a fast car etc. But in Sayles’ script there is more of a social realist feel and while Jill and Sheik are a handsome couple, they aren’t ‘super cool’ Hollywood types.

In the second half of the narrative, Jill goes to college and Sheik goes down to Miami to pursue his dream of singing like Frank Sinatra. He has always dressed like a rat-pack member but what he experiences in Miami is ironic in terms of his Sinatra obsession. In truth, both he and Jill are lonely and when he turns up in New York at Sarah Lawrence, Jill is both worried because she doesn’t want to get involved with him, but also relieved she has someone to talk to. Because of Sheik’s Sinatra kick, the Guv’nor turns up on the soundtrack. For a narrative set during roughly 1966-68, the soundtrack is perhaps unusual. Before the money for all the pop songs was found, Sayles had imagined a soundtrack of Springsteen songs. These would not fit the era as such but they would be authentic in a different way as Springsteen was himself at a similar high school in New Jersey at the time when the film was set. In the end three Springsteen songs from 1973-5 made the final cut. The title song is the Shirelles’ 1961 original rather than the Beatles’ cover version. Two songs are standouts representing Jill and her emotions/hopes etc. One is Dusty Springfield’s ‘You Don’t Have to Say You love Me’, a melodramatic song with English words for an Italian original melody. The second is another standout moment in the film when Jill mimes to the Supremes’ ‘Stop in the Name of Love’ after she has gone out for a drive in a borrowed souped up car with Sheik.

The ‘after school’ years are to a certain extent ‘down’ for both Jill and Sheik and Sayles avoids a conventional ‘happy ending’. There is a conclusion but not a resolution as such. This is a social drama, not a teen comedy. There are a few wry smiles likely to be prompted by the narrative but generally this is about two people who struggle to find themselves and it seems pretty real to me. I was particularly taken by Rosanna Arquette when I first saw the film and even more so on a second viewing. Vincent Spano was in a few more interesting titles later in the 1980s and I will certainly look out for him if I see any of them. The film was generally well-received by critics but Paramount’s executives hated it and basically dumped it in a handful of cities with little real attention to selling it to its audience. Sayles complains that they didn’t even exploit the soundtrack album fully. According to Molyneaux (2000), Sayles’ original cut of the film was 140 minutes. He had worked with an editor, Sonya Polonsky who he would use again on Matewan, though he often edited his films himself. He has always been criticised for making his film too long and complex (which may be partly because his novels are also long and complex). Paramount insisted on a 105 minute cut and did actually re-cut a version with their own editors which then tested poorly so they compromised by allowing Sayles to cut it his way, but still producing a 105 minute film. Paramount’s decisions seemed self-defeating and in the end they seemed to act out of spite. Molyneaux argues that the film was later hard to find in either video shops or on cable TV. The situation was much the same with UIP the distributors Paramount owned with Universal that handled overseas distribution. Baby It’s You and Brother From Another Planet, Sayles next self-produced film, both appearing as new releases in the same issue of Monthly Film Bulletin in the UK in 1984. Baby It’s You was released by Mainline, a small independent distributor owned by Romaine Hart who also opened a small chain of art/indy cinemas starting with The Screen on the Green in Islington. Sayles knew his film (from Robinson’s story) appealed most strongly to women aged 25-35. I think Romaine Hart probably twigged that.

Here’s the scene in the canteen when Sheik makes a move on Jill. The Springsteen song is ‘It’s hard to be a saint in the city’:

Resources

Gerry Molyneaux (2000) John Sayles, Los Angeles: Renaissance Books

Gavin Smith (ed) (1998) Sayles on Sayles, London: faber & faber