Shimizu is an important Japanese film-maker, though he has been overshadowed by other film-makers like Mizoguchi Kenji and Ozu Yasujiro. Both of these film-makers admired Shimizu;

“Ozu and I create films through hard work, but Shimizu is a genius.” a quotation by Mizoguchi Kenji.

“A friend and contemporary at Shochiku of Ozu Yasujiro, Shimizu was one of Japanese cinema’s most individual talents, and seems at last to be receiving the recognition for his subtle, spontaneous technique, and humanity of his oeuvre.” (Alexander Jacoby in A Critical Handbook of Japanese Film Directors).

Despite Alex’s final note of optimism the films of Shimizu remain very difficult to see. A four title box set by Criterion seems to have been withdrawn. So it is both laudable and exciting that the Museum of the Moving Image in New York together with the Japan Society is offering a substantial retrospective throughout most of May. I was fortunate in being able to attend the opening weekend presenting both silent and early sound films.

MOMI is screening the films that Shimizu made for the Shochiku studio between 1931 and 1941. Shochiku, initially a theatrical concern, moved into film in 1920 and continues to this day. It was noted for using western-style techniques, as in the films made in Hollywood. In the silent era Japanese film was dominated by the Benshi, a narrator who stood alongside the screen improvising dialogue, commentary and even sound effects. Shochiku was an early studio to use onscreen titles, making Benshi style commentary redundant. It was partly because of the pressure from Benshi to retain their function that Japanese film continued producing silent titles up to the mid-1930s.

As with other film-makers a number of Shimizu’s early films are lost. The retrospective opened with a two part silent film from 1931 and 1932.

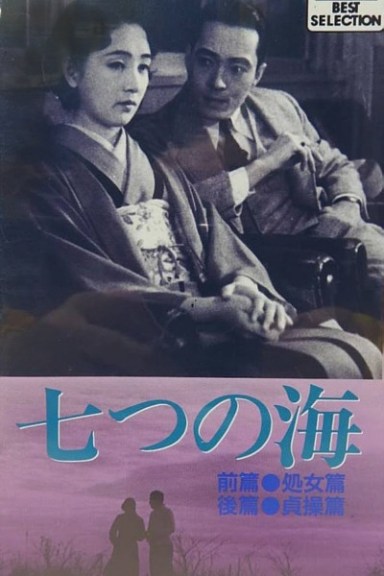

Seven Seas Part 1 Virginity Chapter / Nanatsu no umi: Zenpen: Shojo hen, 72 minutes

The film opens with a distinctive framing; a reverse show of a young woman, dressed in modern style, and standing in the rear door of a final train carriage. She, a Lady, is a minor character but catches the attention of Takehiko, the elder son of the wealthy Yagibashi family. Takehiko shares derogatory comments about the young woman because of her modern style and disregard of traditional values; but he is also attracted. Later the Yagibashi family throw a garden party for the returning Takehiko. Here we meet a number of key characters. Sone Yumie (Kawasaki Hiroko) is engaged to a younger son Yuzuru (Egawa Ureo); her father is a retired civil servant and she has two younger sisters. Also at the party is Ayako (Murase Sachiko) who works as a reporter on a newspaper and is also in love with Yuzuru.

Events following the garden party disrupts the lives of all these characters. The actual event, involving a rape, is treated with great circumspection; though comments by a Benshi may have made the action clearer. The Yagibashi family use their wealth to protect their interests. Yumie’s family suffers a death and the severe illness of one sister. Yumie emerges as a strong willed young woman though adhering to traditional values. Thus by the end of Part 1 she is destined to marry Takehiko rather than Yuzuru who leaves home and becomes independent.

Seven Seas Party 2 – Chastity Chapter / Nanatsu no umi: Kōhen: Teisō hen, 82 minutes

The second film focuses on Yumie’s married life with Takehiko. She crafts revenge on Takehiko and exploits the Yagibashi wealth to care for her ill sister. Yuzuru makes good as a writer and translator. And the Yagibashi family’s wealth and status fail to protect them when another son sells an exposé to the newspapers, causing the family public shame. Yumie and Yuzuru are finally able to find happiness together. However, Ayako is rather left out in the cold and in a slightly odd plotting discovers an absent father and leaves with him for the USA.

The two films run for 154 minutes in total. Both offer a complex plot and a fairly large cast of characters. The films were adapted by Noda Kogo from a novel by Maki Itsuma, [also known as Hasegawa Kaitaro). The cinematography is by Sasaki Taro who also worked on other films by Shimizu. The film has some distinctive stylistic tropes that were common in the silent films of Shimizu. There are some fine tracking shots; and in particular sequence set in a mountain rest home there are a series of pans and cuts across a hillside ending by a lake where we see the inverted reflection of a couple, then broken as the man throws a stone in the water. The style is naturalistic and the mise en scène uses sets and costumes to define the differences between the two families.

The cast are mainly experienced players at the Shochiku studio and are all fine in their characterisations. And the young Takemine Hideko appears as the youngest sister in the Sone family. One of the conflicts in the film is between the traditional and the modern, emphasised in a number of ways including in the dress of the female characters. Thus in one sequence Ayako tells Yuzuru of her love for him, dressed not in her usual western style but in a traditional kimono. Meanwhile Yumie usually wears traditional style dress but in one scene after her marriage confronting Takehiko she is dressed in expensive westerns style clothes.

The main conflict in the film is between the wealthy Yagibashi family, corrupted by their wealth, and Yumie and her family, less affluent but more moral. This relates the film to the ‘social tendency’ titles of the period, where class conflict took centre stage, sometimes with a Marxist influence.

This provided a fine opening to the programme. Whilst the plotting was at time challenging the tone and style of the film made this a pleasure to view.

A Hero of Tokyo / Tôkyô no eiyû, 1935, 63 minutes

The title of this film refers to a male character but the central character is a mother, Nemoto Haruko (Yoshikawa Mitsuko). The film is part of a genre of haha-mono (mother story). A widow with two children she marries a widower, Nemoto Kaichi (Iwata Yûkichi), who also has a young son. Nemoto is involved in a Manchuria-Mongolia gold mining venture. Shortly after the marriage the company is exposed as a fraud and Nemoto disappears. Haruko is left to bring up her own two children, Hideo (Yokoyama Jun as the young boy) and Kayoko (Ichimura Mitsuko as the young girl), and her new stepson Kanichi (Aoki Tomio as the young boy) all alone. In order to support the family she takes a job as a hostess. The job of hostess and of a geisha shaded over into prostitution and in this period suffered from moral disapproval. This point is made when Haruko and her family, after bailiffs take possession of the home and furniture, move into a block of flats and we hear the local women gossiping and claiming she is

“different from our sort.”

Haruko keeps her work secret from the children.

Twelve years later the children are grown up. Kanichi (Fujii Mitsugi) is a newspaper reporter; he appears to be married but the wife is a minor character. Hideo (Mitsui Kôji) and his sister Kayoko (Kuwano Michiko) find their lives disrupted when Haruko’s work becomes public knowledge. This leads to both leaving home and only Kanichi remains supporting Haruko. Then the father re-appears involved in another mining scam. This leads to tragic consequences but Kanichi’s actions lead his role as a ‘hero’.

The film demonstrates the way that Shimizu handles the contemporary society and its issues. Alex Jacoby comments;

“His characters are almost always those who are alienated from the mainstream of society, whether by personal situation (poverty, family breakdown), profession (his men are often artists; his women hostesses or prostitutes), …”.

In this Shimizu’s films parallel those of a contemporary, Naruse Mikio.

This film, like others, also offers a critical sub-text. The scams of the father reference Manchuria, which in this period Japan invaded and where they set up a puppet government. Alex comments,

“the father is, metaphorically, a representative of the militarists and of the business interests that colluded with them…”

I could not see a writers credit so it seems that this is very much down to the director; he was known to improvise with his production teams. Some of his films did not have a formal script but more a story line which he could change and vary as filming progressed.

The cinematography is by Nomura Hiroshi who worked on a number of Shimizu films in this period. And the film displays stylistic tropes which feature in several of these. One distinctive trope appears in the opening the film. We see a shot of a number of boys sitting on large pipes alongside a railway line. Several dissolves gradually reduce the number of boys to only one, the young Kanichi. In another shot with all the boys present they tease Kanichi because his father comes home later than theirs. Kanichi replies that this is because his father is more successful in business. The comment is repeated later in the film with a touch of humour; the mother arriving home late the stepson asks if she has been promoted.

Shimizu also has a tendency to open scenes with people’s feet in close-up. Late in the film this is seen in a scene following a criminal act and the arrival of police. These distinctive techniques contribute to Shimizu’s reputation as a stylist. He has a great sense of mise en scène; one nice touch in the film is when we see the young boys drawing each other and then the drawings appear later in the film as family dissensions disrupt the earlier relations.

This was Shimizu’s final silent film and it had a music track recorded on a Tsuchihashi sound system, though Shochiku went on to develop their own sound system.

Japanese Girls at the Harbour / Minato no Nihon musume, 1933, 78 minutes

This is an early masterpiece by Shimizu. In the notes for the Criterion Eclipse discs Michael Koresky writes

“with its delicate social commentary, rendered in minute gestures and precise mise-en-scene, is a perfect example of his naturalistic yet symbolic technique, as well as a proper introduction to his abiding interest in life’s outliers'”

The film is set in the port city of Yokohama and an early title identifies ‘The Foreign Settlement’ as the setting. Yokohama was one of the ports forced open by U.S. gunboat diplomacy in mid-C19th; Britain joined in and the developing city acquired a protected compound and even a servicing commercial sex district. The extra-territorial position ended in 1899 but it seems that the city retained an openness to western influences and imports.

The two Japanese girls are Sunako (Oikawa Michiko) and Dora (Innoue Ichiko), close friends who attend a European-style school and appear to live in a dormitory at a convent, [though we do not see any nuns). We first see the girls in a cliff-top viewpoint as a liner sails away. Here they meet Henry (Egawa Ureo), who rides a Harley-Davidson motor cycle, and is admired by both young women. However, it is Sunako who is his girlfriend and the two ride off together leaving Dora alone. Later we, and Dora, discover that he is connected to a group of likely petty criminals, [‘those hoodlums’] but also that he has another older girlfriend, Yōko (Sawa Ranko). Learning of this leads to a confrontation between Sunako and Henry and Yōko in the church [likely Catholic] alongside the dormitory. The result of this is that Sunako leaves Yokohama and seems to wander through several cities. We find her again in Kobe, another once extra-territorial port. Here she works as a geisha in a bar- i.e. a prostitute. Her fellow geisha is Masumi (Aizome Yumeko) and Sunako also has a sort of camp follower, Miura (Tatsuo Saitō Tatsuo), an itinerant painter who constantly paints portraits of Sunako. Masumi prompts Sunako to accompany her back to Yokohama to work in a bar run by Harada ( Nanjō Yasuo). Here Henry has married Dora and Sunako’s return creates a disruption in their lives and a turning point in hers.

This melodrama is finely presented and the cast convince in often emotional sequences. As Michael Koresky noted Shimizu frequently uses location filming and there are many fine exteriors in the film. The cosmopolitan air of the cities is captured; nearly all the characters wear western style clothes; the exception is Sunako when she becomes a bar hostess and dresses in a traditional kimono. The casting reinforces this sense: Oikawa Michiko was born to Christian parents, her film career was cut tragically short a the age of 29: both Innoue Ichiko (half-Dutch) and Egawa Ureo (partly of German descent)have something of an Eurasian look. And the motor cycle, the liners and the cars we see on a quayside, all betray strong western influences.

The mise en scène and the cinematography have numerous examples of Shimizu’s distinctive stylistic tropes. There are two fine tracking shots along the cars on the Yokohama quay where a ball is held. The use of dissolves to place and displace characters are really effective; frequently we see a shot of a character caught perhaps in a doorway; the following dissolve presents the same doorway with the character vanished. The most notable technique, and likely very rare for the period, occurs at the dramatic confrontation in the church; a series of jump cuts first ‘zoom’ in on a character then reverse out again. And later in the film a repeat series accompanies a moment of dramatic recognition.

The camera often places characters in doorways or through windows and with deep staging. And one memorable set where Sunako resides uses blocking of objects and bars to comment on the scene and the characters within. Props also become significant. In the home of Dora and Henry we see at one point a ball of wool which entangles characters; a little later the passing of a skein of wool comments on characters responses. Shimizu also uses cutaways to emphasise the emotional content of a scene. Thus, we watch a scene as someone dies and the several cutaway shots present an exterior with rain and a flower perched in a slot near the window of the room where they lie.

The titles and sub-titles of the print are distinctive. Titles that comment or provide information are in the Japanese equivalent of upper case: titles presenting dialogue use inverted commas with a capital and then all lower-case. The sub-titles in English follow this but without the inverted commas.

Shimizu’s films have parallels with those of Naruse Mikio, especially in the use of characters outside or excluded from respectable society. In Naruse the resolution is often downbeat, though with heroines determined to ‘soldier on’. Shimizu’s resolution tend to be more hopeful.

Note, plot information.

In Japanese Girls at the Harbour the resolution is an example found in Michael Walker’s research and analysis’s of Endings in the Cinema (Palgrave Macmillan 2020). Under ‘Water – Ship and Boat Departures’, he notes,

“At the end, Sunako asks Miura to throw his two remaining paintings of her into the harbour – which he does. The liner then leave, and much emphasis is given to the severing of the streamers connecting the passengers on the ship to the people on the key seeing them off. Only after the liner is sailing away do the film’s other couple, Dora and Henry, arrive. They join Harada, Sunako’s ex-pimp, who is still observing the liner; he tells them, a little mockingly, ‘they sent you their regards’. Their lateness is a reflection of their ambivalence towards Sunako, who at one point, jeopardised their marital happiness. After Harada has left, the couple continue to stand and observe the liner, but the film actually ends with images which stress the threshold and, in the distance, the departing liner: a shot from the beach, then shots from the quayside as torn streamers blow in the wind. The shots no longer include characters, and with each one the liner is further away; finally it is gone. The last shot is one of Miura’s panting of Sunako floating in the water.

Although the emphasis here is on the ship’s departure itself, the final image carries another intimation. Sunako’s portrait floating in the harbour suggests that a part of her will remain in Japan. “

The sequence of shots take on added resonance as the film opens with a departing liner and the cutting of streamers from shop to quay. Sunako’s destination is not stated, and whilst she and Miura are on an ocean going liner she is still dressed in traditional Japanese garb. I should add that it is Henry, as much as Sunako, who threatens the marital order. He is one of those rather weak and ineffectual males often found in melodrama, where as Dora and Sunako are stronger characters.

I have been fortunate to see this film twice on 35mm. Even on second viewing I was discovering fresh resonances among the characters and fresh stylistic tropes and the way they illuminate characters. I find this a genuine classic of Japanese film.

Seven Seas and this film were accompanied on an electric piano by Matsumura Makia who received well deserved applause. She is a frequent accompanist for silent film around New York. She has a fine lyrical style. Her accompaniments contributed to both the emotions and the pleasures of these films.

Forget Love for Now / Koi mo wasurete, 1937

35mm print from the Japan Foundation. 73 minutes.

Director; Shimizu Hiroshi; screenplay Saito Ryosuke; cinematography Aoki Isamu. Music Ito Senji and Ozawa Akiyasu.

This was an early sound film with a central woman character, Yoki (Kuwano Michiko), working as a hostess in a Bar in Yokohama. But the main focus of the film is her son Haru (Yokoyama Jun credited as Kozô Bakudan). Shimizu was noted for his work with children and some of his best known films deal with child centred narratives. The milieu of the film is very much the working class port area. Thus the shame constant in the adult world is absent, but Haru suffers because of his mother’s work. When the film opens Yoki is working in a bar frequently patronised by foreigners, including men working on liners. Her work means she has to leave Haru alone much of the time. He is part of a gang of young boys but soon he becomes the object of bullying. He finds some solace in an alternative gang, this of young Chinese orphans. But the bullying continues and disrupts his life. Meanwhile Yoki has problems with the Madame (Okamura Fumiko) who runs the bar. She is befriended by a man, Kyôsuke (Sano Shûji) who initially is sent to keep an eye on her because of her complaints to the Madame. Kyôsuke also befriends and tries to help Haru. But the bullying of Haru continues and the violence between the boys increases as he fights back. Some of this is in the street, but mainly in an old wooden building with a disused boat lying there. The climax of the film occurs here and the narrative reaches a tragic conclusion.

Shimizu’s handling of the young actors is very fine; and this is a quality found across his films dealing with child experience. Much of the film is taken up with the interactions between boys and their gangs; these are entirely convincing and develop the drama of the film.

Befitting the downbeat tone this is a film full of shadows, misty streets, nighttimes and much low key lighting. As in his silent films Shimizu and his cinematographer, Aoki Isamu, also use tracking shots, dissolves and some notable deep staging. Much of the film was shot in studio sets, unlike many other films, but presumably offering greater control over camera set ups, lighting and sound. The sound track includes appropriate music by Ito Senji and Ozawa Akiyasu. There is a repeated song with a notable gloomy tone, though the lyrics are not translated.

The introduction by the one of the curators made the point about Shimizu’s work with children. He also pointed out how, like Japanese Girls at the Harbour, the film uses the multi-cultural milieu of Yokohama to good effect. The foreign clients of the bar only patronise the hostesses when a ship comes in; a point of excitement in the bar, though also of some tension between local and foreign men. The points emphasised as one of the hostesses is a young white woman, Mary (Mary Dean). There are also the Chinese orphans and the point was made that this carries a subversive political significance as this was the period of the Sino Japanese war.

Yoki is a leading spirit in complaints about how the hostesses are treated. This results in the use of Kyôsuke to keep an eye on her. Later she is fired. But another hostess is beaten up by hired thugs when she tries to leave the employ. Her situation is tragic but the dramatic and emotional centre of the film is the resistance and suffering of Haru .

A Woman Crying in Spring / Nakinureta haru no onna yo, 1933, 96 minutes

This was Shimizu’s first sound film and it offers dialogue, songs and sound effects. Shimizu continued making silent films up until the late 1930s. The film is set in the northern region of Hokkaido. It has a harsh climate with frequent and heavy snowfalls in winter. It is also close to Russian held islands, some of which are claimed by Japan.

The film opens as heavy mining equipment is loaded onto a ferry. This is followed by a troop of workers going to labour in the mines. They are commanded by a boss, Yasu Sarge (translated as The Sergeant – Ôyama Kenji). As he lines them up on the ship he tells them the ‘three commandments’;

“No women. No booze. No gambling”

He also finds a latecomer, Kenji (Obinata Den), who is travelling with his friend Chû-kô (Ogura Shigeru). Following the man on board are a group of women led by Ohama (Okada Yoshiko). She plans to open a bar where the women will act as hostesses for the men at the mine and local soldiers.

Kenji’s character is established when, ignoring one commandment, he wanders round to the women on the boat and cadges a cigarette. He meets Ohama and also her young daughter Omitsu (Ichimura Mitsuko). He also notices a young woman with an ‘Osaka accent’, Ofuji (Chihaya Akiko); it is clear that she is new to this line of work and is unhappy. Once arrived the men are housed in bunk rooms and start work in the mine. Kenji persuades the Sergeant to accompany him to Ohama’s bar, happily ignoring all the commandments. There he fights off a local soldiers who attacks Chû-kô. Ohama is immediately attracted to Kenji. But he seems as interested in Ofuji. She confides that her mother at home is ill and she wants to send her money and to visit her. Meanwhile it is clear that Ohama takes little notice of her daughter and the Sergeant develops an attraction for Ohama herself. The other women in the bar discuss who will win out in this quartet. We see little of the work in the mine but a cave-in leads to increasing conflicts between the men and at the bar. The ending is downbeat for some but hopeful for others.

In his introduction Choi Edo stressed the inhospitable climate in Hokkaido. He added that Shimizu went to school in the region and found it an oppressive setting. The film presents a bleak climate in which the drama develops. The film is mostly a studio production and uses frequent low-key lighting. In a review of the film which he sees as in a style like the silent titles Joseph Sgammato comments;

“For the film is dominated by the look of German expressionism wedded to the need to communicate stories without words. We have, among other features, the characteristic attention to the make-up of the frame, marked by diagonal linear compositions, lighting that suggests nothing so much as an interruption of darkness, and the visual exploitation of windowpanes and doorways, all overlying a series of vignettes that drive a thin plot more circular than forward-moving (in other words, more Japanese than Western).”

The film also uses typical Shimizu tropes such as tracking shots and dissolves. And there are frequent use of blocking on screen; a notable example is a fight at the mine where the camera shoots from behind a snowy mound, then a pump and finally through snow covered branches. Shimizu uses sets and props to good effect: the staircase from the bar up stairs to the rooms of the hostesses is one; and the doll of Omitsu is another. The cinematographer Sasaki Toro worked on a number of Shimizu productions; likely this was his first sound film. The dialogue in the film is important but it is supported and emphasised by a series of songs. The lyrics of these match the downbeat drama; an early song, repeated in the bar, includes the line ‘I’m down and out’. The film had quite a number of assistant directors, a team of editors and a team of sound engineers working with Shimizu.

Okada Yoshiko and Obinata Den lead a strong cast whose playing is excellent. And Ôyama Kenji is effective in an unsympathetic part. The plot is a rather familiar one; in an ironic line the Sergeant tells Kenji ‘enough melodrama’. But the film develops a strong narrative effect and some emotional moments.

Mr. Thank You / Arigatō-san, 1936, 75 minutes.

This seemingly pleasant comedy-cum-drama has a series of subtexts which, as usual, provide a rather subversive representation of Japan in the mid-1930s. The film follows a small bus travelling from Izu in a mountainous region in southern Japan. Some synopsis suggest the bus is taking passengers to Tokyo but it seems that it is taking them to a station where they can catch a train to Tokyo.

Choi Edo in his introduction drew comparison with the films of Jean Renoir in the popular front period. A number of writers have made such comparisons; there is the focus on ordinary working class people: on people outside the mainstream of society: of an affectionate characterisation of such people: and of a somewhat left-leaning critical perspective. Choi also noted that the film is shot entirely on location. Sara Smith, in an essay on Shimizu, comments on this;

“I could feel the breeze in my hair as a the landscapes whipped by: shining surf fanning over beaches, craggy mountains rising and falling like waves, all glistening in smoky sunlight. In a recurring motif, the camera takes the POV of the bus as it comes up behind carts, rickshaws, and pedestrians, then dissolves to a shot looking back at them as they recede, as though the bus passed right through them. The driver, played by matinee idol Ken Uehara, earns his nickname by calling out a hearty “Arigato-o-o” (“Thanks”) to everyone who makes way for his lumbering vehicle. On board, the passengers form an ephemeral community, bickering and singing, sharing snacks and tales of depression-era hardships. One by one, they disembark and disappear.”

The film opens with Mr. Thank You driving the bus towards Izu. He passes a horse and cart, labourers, women workers, geese and chickens: then arrives at the bus depot and waiting passengers. Certain passengers are picked out in detail: there is a mother (Futaba Kaoru) taking her daughter (Tsukiji Mayumi) on the first stage of a journey. Only seventeen she is being sold into service, [likely some form of prostitution]; she and the mother express the shame that is attached to such work. There is a modern style young woman (Kuwano Michiko) who provides a sort of commentary on the passengers. And nearly missing the bus and only just catching it is an older man, (Ishiyama Ryuji), who seems to be some sort of commercial traveller.

The young modern woman calls the latter a ‘badger ‘ and ‘foxy’ when she catches him ogling the daughter. The terms seem to be slang for male chauvinist pig in modern parlance. She also passes round drinks for the passengers and makes pertinent comments to Mr. Thank You. The traveller constantly complains and finally leaves the bus before the arrival at the destination. There is also an older man in the back seat; I mention him because the programme trailer which we saw several times is bookended by a humorous use of shots of this character,.

In addition there are a number of people who Mr. Thank You stops and greets on the journey. these include villagers: labourers: young women with requests: a young woman with a message to pass on: hikers as they approach a mountainous pass: a husband who needs to fetch a doctor for his pregnant wife: and, not stopped for, a group of boys hanging on the rear of the bus. Two of the most interesting include a young Korean women who is working on construction projects. She asks Mr. Thank You to tend the grave of her recently deceased father.

Sara Smith notes,

“Shimizu’s plein-air method of working was unique. He often travelled to remote areas, bringing a few leading actors and casting local non-professionals in other roles. Starting with a loose script, he built up from improvisation and chance, using a musical sense of repletion and variation around a whisp of plot'” The young Korean woman is such, when Shimazu met a group of Korean workers on the road he improvised this sequence.

The other group he meets is an all-woman kabuki troupe; I knew nothing of such ventures. They are publicising their performance of ‘The Lives of Five Thieves’ in a local village.

It is clear from the journey that Mr. Thank You is a well-known and well-loved character in the region. We end with the bus making the return journey. In fact, not all the passengers have departed. And the resolution provides a more upbeat ending which again bears comparison with Jean Renoir.

This is a delight to both watch and listen. The cinematography is excellent, with most of the now recognisable tropes of Shimizu in use. The sound, especially give the location work, is impressive. And the music has a lightness that suit the plot and characters. The print in places tended to dupe, I figured it was likely a combined print. But that did not really detract from the pleasure. The cast and crew all deserve fulsome praise. And there is the usual subversion as the narrative draws attention to the problems of the depression-era: to the exploitation of women: and, notably, the exploitation of colonized labour.

Children of the Wind / Kaze no naka no kodomo, 1937, 86 minutes.

Another sound film which seems to use both studio sets and location shots. Like Mr. Thank You some reviews regard the film as ‘lightweight’; but in both cases whilst the films mix comedy and drama they also contain underlying critical representations. This is one of the child films for which Shimizu is known and Choi Edo in his introduction explained that it was the most popular of his films Japan, an adaptation from a novel. He also made the point that the film displays Shimizu’s talent for directing children and bringing out their experiences and point-of view.

The film focuses on two brothers, Zenta, the elder, (Hayama Masao) and Sampei, the younger (Yokoyama Jun, credited as Kozô Bakudan). We first meet then returning home from school and having an argument about grades on report cards. Zenta claims to have ‘excellent’ and crows over the other boys, including a neighbour’s son Kinta ( credit not found). At home their mother (Yoshikawa Mitsuko) is pleased with Zenta but worried about Sampei’s poor report. After evening meal, whilst Zenta can go out to play, Sampei has to stay in for ‘study time’ The study texts reference western culture, ‘Robinson Crusoe’ and ‘Tarzan’. Sampei studies, reading aloud, very loudly; something he does frequently. But later he sneaks out to join Zenta and the neighbourhood gang which they lead.

But Kinta starts to claim that their father (Kawamura Reikichi) has been sacked from the company where he works. This appears to be some sort of factory with the father employed as a manager and/or accountant. The resulting conflicts later leads to Sampei hitting Kinta with a stick. This exacerbates matters; especially as Kinta’s father is a shareholder in the company.

Zenta and Sampei constantly argue but also play together. The mother explains her concerns to their father, who appears less concerned. And he plays with the boys in a mock sumo wrestling match.

Every day one of the boys takes their father’s lunch to the factory. This is usually Zenta but when Sampei’s reports improve he is allowed to do this. This is an unfortunate day. Arriving at the factory Sampei finds this awry. His father does not explain matters but it is clear that he has been suspended or fired. At home the father tells the sons that this will be a ‘summer vacation’. There is a scene where the brothers play at ‘Olympics’; whilst Sampei goes through the motions of swimming on the floor, and under a carpet ‘underwater’, Zenta provides an excited commentary. Then the father is arrested and charged with fraud. Kinta, now leading the boy gang, triumphantly mocks the brothers. Whilst Zenta has to be found work, as the family income is disrupted; Sampei is sent to stay with relatives. The travails continue until evidence clears the father and family life is reinstated; as is the brothers roles in the neighbourhood gang.

Alex Jacoby comments on the children films of Shimizu,

“The most recurrent narrative trope is that they focus on individuals who are excluded from the group …”

“thus, in Children in the Wind, two brothers are ostracized by their fellows because their father is suspected (unjustly|) of embezzlement; while in Forget Love for Now, the hero Haru, is rejected by his schoolmates because his mother supports him by working as a nightclub hostess.”

In both films the problems of social class and of the depression years underlie the narrative; in the latter in a much darker way than in the former. Whilst the depiction of the boys, [we do not seem to see any young girls] is often playful it is also the case that their world is dominated by the world of adults. The problems and conflicts of the adult world interact in the world of the children.

The cast, adult and child, is excellent. The young boys are always convincing, both in their play and in their problems. Yokoyama Jun as Sampei in particular makes much of his character. His study times are amusing if frustrating for the adults in the film And there is one powerful scene, where Sampei takes the lunch to his father. Sampei is not told what is occurring but he senses the almost tragic situation of his father. He stands and waits. meanwhile the other boys gather at the window, clearly following the disruptive events at the factory. Sampei slowly pulls down the blinds of the office one by one; shutting out the prying eyes.

The cinematography is fine, both interior and exterior. And there are the by now familiar tropes of Shimizu’s work. There are a number of the distinctive dissolves; one showing Sampei at his study desk and then merely the empty desk. The Olympic sequence and the two sumo wrestling sequences are all great fun. The music follows both the comedy and the drama, with suitable emotive tones for the latter. One can understand the popularity of the film; but it is more than a neat drama or feel-good movie.

A number of actors and craft people turn up in several of the Shimizu films screened here. All were working at the Shochiku Studio in this period, so there is the familiarity and shared experience that one finds in a classical studio model. Clearly the studios long-running success over a century rests to a degree to the quality of its productions in these founding decades.

Shimizu’s titles are often intriguing. Japanese Girls at the Harbour emphasises place: whilst A Woman Crying in Spring seems a metaphor using the seasons: and Children in the Wind uses weather as a metaphor. A Hero of Tokyo feels like it should read ‘heroine’. Mr Thank You suggests a character and approach that frees itself from the traditional Japanese restraint. And Forget Love for Now seems like advice to the many hostesses in that and other films.

The films were accompanied by printed notes for each title available before the screenings and introduced by Choi Edo, Assistant Curator of Film at MOMI and Alexander Fee, the Film Programmer at the Japan Society. I have noted some of their comments alongside individual titles. Both provided helpful information and drew out some of the developing aspects of Shimizu’s early film career.

The Museum of the Moving Image is sited in the old Astoria Studio in Queens’ Borough. It has a permanent exhibitions on the production side of the industry and one dedicated to the work of Jim Henson. There are also frequent temporary exhibitions and a small book shop with some interesting titles. There are two film auditoriums; the larger Redstone, seats over 250 people and is a large airy space. The projection box, which look spacious can handle 16mm, 35mm and 70 mm prints [Century JJ 35/70mm projectors and a Elmo LX-2200 for 16mm], plus digital files. At weekend there are regular screenings of films, both contemporary and classic, including silent films. All, bar Forget Love for Now, of the retrospective prints were screened in Redstone auditorium. One of the practices I have found and enjoyed elsewhere in the USA is the audience expressing appreciation for the projectionists. So we applauded Carolyn Funk, Joseph Stankus and Fred Baez, who handled the sometimes delicate and worn prints very well. And Rebecca Fiore, Manager of Visitor Experience, kindly handled all our questions. The prints, with English subtitles, mainly came from the National Film Archive of Japan; the exception, Forget Love For Now, was from the Japan Foundation, who also provided its subtitles. The curators explained that the prints are not restorations but surviving ones at Shochiku, so they were limited to single screenings of each title. They are also destined for a further programme screening on the U.S. West Coast. Hopefully the studio will produce new prints and possibly proper restorations.

I was able to discuss the films with my friend Bob Mastrangelo, who made some helpful observations. He contributes the annual obituary article for Sight and Sound. He remembered including a couple of the long-lived cast members in earlier years; this included Inoue Yokiko who died in 2012 at the age of 97. Bob also saw some of the later titles in the retrospective. The Masseurs and a Woman / Anma to onna (1938) featured one of the greatest stars of Japanese cinema, Takemine Hideko. And he also liked A Star Athlete / Hanagata senshu from 1937. There is a second part of the retrospective at the Japan Society venue. The films feature Shimizu’s post-war work including what is perhaps his most famous title, Children of the Beehive / Hachi no su no kodomotachi (1948, which I was fortunate to see at an edition of Il Cinema Ritrovato. A number of his surviving films were shown at the 2010 edition of Le Giornate de Cinema Muto. And the BFI South Bank had a major retrospective in 1988. I was really happy to have caught even some of these memorable films. If any titles by Shimizu happen near any readers I strongly recommend them. If one of the 35mm prints happens then they are very fortunate.

Quotations from the English subtitles on prints.

Sources of material in the Film Programme Notes.

“Hiroshi Shimizu: A Hero of His Time” by Alexander Jacoby on Senses of Cinema, July 2004..

A review of A Woman Crying in Spring by Joseph Sgammato on Senses of Cinema, April 2021.

Notes on the now deleted Eclipse Criterion Box set by Michael Koresky, Travels with Hiroshi Shimizu, 2009.

“Hiroshi Shimizu – Silent Master of the Japanese Ethos” by William M. Drew, Midnight Eye, April 15, 2004.

An essay “Passing Through: Discovering Hiroshi Shimizu” by Sara Smith, Reverse Shot, May 2, 2024.