Do you ever think twice about going to the cinema on a Sunday? It probably depends on the age or religious beliefs of individuals but in the UK today generally there isn’t now much difference between Sunday cinemagoing and any other day of the week. Your local cinema will usually show the same programme on every day of the week, though specialised cinemas may have a specific Sunday offering like a Sunday Matinee Classic to complement the regular programme. The other aspects of what is on offer as a Sunday diversion are also mainly open, including shops and galleries and museums. The exception is theatres. Outside of London’s West End most regional theatres keep Sunday clear to give cast and crews of shows a breather. This is a practical decision and is linked to arguments about workers’ rights to have rest days.

But flashback to the 1950s and Sundays were very different. Shops rarely opened on Sundays and in many places cinemas too might be closed. Pubs were not open all day and there was no football to watch. And when cinemas were allowed to open they faced various kinds of restrictions. There was a famous episode of Hancock’s Half Hour on the radio titled ‘Sunday Afternoon at Home’ (1958) and John Osbourne’s play Look Back in Anger (play 1956, film 1959) takes place mainly on Sunday afternoons. In both cases the principal characters were bored to tears and therefore likely to get up to certain kinds of mischief.

The reason I’m writing about this now is because of a dialogue with another blogger about the double bill of Don’t Look Now and The Wicker Man which opened in December 1973 in London. We discussed when the films were released and how cinemas programmed them. In the image of cinema listings above, the double bill is shown in the display listing. As this is a Thursday edition, I’m assuming that unless shown otherwise, the films are showing for the next week. Note, however, the running ad for Burt Lancaster in Scorpio which opens at the Abbey Cinerama in Wavertree on Sunday. See below for more on this but I soon realised that though I remembered isolated examples of Sunday cinema, I hadn’t researched it properly. I decided to look for the main points of the history.

Cinemas in the UK have been subject to government legislation since the Cinematograph Act of 1909 which required local authorities to issue licences to film exhibitors who would in turn be required to meet safety standards re fire risks (nitrate film was highly combustible) and the provision of enough exit doors to safely evacuate the premises. In 1932 The Sunday Entertainments Act then required licensing authorities to control opening hours on a Sunday. If cinemas were to now open on Sundays, they could only do so if they followed licensing regulations re hours of operation. In addition they must not employ staff in the cinema on a Sunday who had worked continuously for the six preceding days and thirdly the cinema must pay a levy at a rate decided by the local authority to the Cinematograph Fund – funds from which were initially used to set up The British Film Institute. In the 1920s and early 1930s various campaigns by church groups had urged the closure of cinemas on Sundays for two main reasons: the popularity of cinemas might deter churchgoers from attending Sunday services and the depravity and generally lax morals of film narratives were anti-Christian. If local authorities thought that these campaigns represented the majority of their local ratepayers, they could keep cinemas closed on Sundays. But the Act also allowed them to hold a poll and to abide by the results.

The overall result of the new legislation (which was applicable only in England and Wales – Scotland and Northern Ireland had separate legislation) was that Sunday film screenings were stopped in some local authority areas and available in others, albeit with restrictions (e.g. not open before 4.30 pm). Anyone living near a local boundary might find that two cinemas relatively close to each other could be differently affected. Before the Act in 1929 a new cinema in Blackpool, the Empire, was opened on what had been farmland just outside the then borough boundary. As a result, the entrance to the cinema was on a road in Blackpool but the auditorium was over the boundary in the Fylde. Application for a Sunday licence (Blackpool allowed Sunday openings) was then made in Fleetwood (presumably under Lancashire County licensing like other smaller districts in the Fylde) which allowed a special licence to avoid a difficult problem. (See the Bioscope report 21/8/29) Another account reveals the ‘undemocratic’ practices in some areas before 1932. In Picture House 30, 2005 there is a long article based on the notes of Alfred Davis, whose family built the Davis Theatre in Croydon. When it opened in 1928, The Davis Theatre had nearly 4,000 seats and was the biggest cinema in England. At that time Croydon didn’t allow Sunday opening. Davis recalls that a solicitor applied each year to the council for a licence on behalf of the thirteen cinemas in the borough. The Conservatives ran the council and they supported the main opposition to openings represented by the Bishop of Croydon. The Labour councillors were ‘pro’ but only held a third of the seats. There were 100 churches in the borough forming a strong group opposing Sunday opening. But when the 1932 Act established the case for a referendum, Davis ran a campaign to persuade ratepayers to vote for Sunday openings. He makes the point that only around 30% of the 100,000 ratepayers usually voted in elections, but in this case 60% or 60,000 voted with 35,000 in favour and 25,000 opposed.

When circuit cinema programming began to develop in the 1930s it became clear that Sundays were ‘different’. One of the most detailed accounts of ‘Sunday openings’ draws on the detailed returns sent by the manager of the Sheffield Gaumont to the circuit’s head office during the years 1947-58. Copies of these returns were sent by an ex-manager of the cinema to Allen Eyles, the cinema historian and editor of Picture House, the magazine of the Cinema Theatre Association. Allen Eyles incorporated some data in his book Gaumont British Cinemas (CTA/BFI 1996) and a comprehensive analysis by Sheldon Hall was published in Picture House 42, 2017 During most of the period discussed by Hall, the Gaumont programmed a circuit release from head office for the six days, Monday to Saturday, but Sunday was a separate operation and this was usually a single film programme of a re-release film. The cinema records show that in the early 1950s the best Sunday takings would be around £300 going down to the weakest under £100, the median take was around £170 net receipts (excluding booking fees). This compares with daily figures Monday to Saturday that were considerably higher at around £400. The reasons for this are clear. The circuit release was a ‘first-run’ film on most occasions which, even as part of a ‘full supporting programme’ would run at least three times a day. The Sunday film was likely to only run twice.

Hall also points out that many of the Sunday screenings were of ‘action films’ which were more likely to attract a male audience. He surmises that cinema managers perhaps assumed that ‘working men’ might be less likely to come to films mid-week. Later it was apparent that some cinemas began to focus on younger audiences when admissions declined more steeply in the late 1950s. I’ve seen accounts of some very noisy audiences of ‘teen to twenties’ for Sunday evening shows.

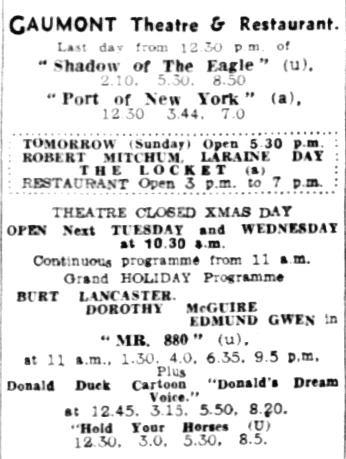

I started to look at cinema ads in other towns and cities and I realised that practices actually varied considerably. In small towns cinemas were closed on Sundays in the 1950s. Non-circuit cinemas and especially those designated ‘second-run’, usually changed programmes twice a week with Monday to Wednesday and Thursday to Saturday and then a third programme on the Sunday if the licence allowed. But in Blackpool in 1933 I found some cinemas showing the same programme for seven days (but on Sunday there were no matinees). The Sunday Cinema Act 1972 repealed the 1932 Act, abolishing the statutory payment of a levy into the Cinematograph Fund and took away the constraints on licensing Sunday exhibition. Subsequent Acts have consolidated the legislation affecting cinema exhibition.

To return to Don’t Look Now and The Wicker Man, which I saw in the second half of its ‘West End’ run on Friday January 1974 at the Odeon High Street Kensington. Note from the ad above that even though there is a Sunday programme, it doesn’t start until 4.40 pm. I was surprised to read that it opened on a Thursday. I was then equally surprised to discover that subsequent screenings in London suburban cinemas started on a Sunday. The new legislation allowed this practice without restraint, but it begs the question, “Why open a film on a Sunday?” and I haven’t found the answer yet. The obvious point to make is that the distribution/exhibition ‘ecology’ of the modern era means that, like the US, the UK has followed the ‘three day weekend’ opening model for around thirty years and if you are so used to this model, the older practices seem very odd.

The 3-day weekend model’ means that cinemas and distributors can decide if a film will be a success after just three days – Friday, Saturday and Sunday. On Monday decisions are made about whether a film will be retained or moved to a smaller auditorium etc. on the coming Friday. The assumption is that because the three weekend dates usually take more money than Monday to Thursday only the first three days really matter. But this model is actually full of holes. As we’ve noted on this blog before, certain films actually do very well in mid-week with certain audiences who prefer a quiet Wednesday afternoon rather than the crush on a Saturday night. Also, it means that the system ignores those films that ‘grow’ an audience through ‘word of mouth’ and could even have a better take in Week Two. We can also note that the opposite applies if you start a film on a Sunday. If the film doesn’t work ‘bad word of mouth’ might kill it before it reaches Friday/Saturday when its big audiences are expected to turn up. Computerised ticket returns meant such a practice became possible. It needed several days to put changes into effect because physical prints had to be moved, but more recently with virtually all screenings from DCPs easily transferred, any film can play in any cinema (at least theoretically). In practice the big players still control the market and smaller cinemas can’t always get the best deals.

The other factor to consider is that back in the early 1970s, without the internet, films from Hollywood studios often opened in North America several months before overseas territories. Now, for the biggest budget films the opening is worldwide to avoid piracy. You might argue that since digital distribution the whole system has changed again. Yes, films do now open on any day of the week, for all kinds of reasons, but the three-day weekend model still holds on in the sense that the box office reports still publish the weekend figures. The history is, I think, important. There are many ways to organise distribution and exhibition and I think we are still in something of a temporary flux following COVID and the unresolved question of ‘cinema windows’ and the strategies of the streamers.

What can we learn from these distribution issues? I think the first point is that distribution and exhibition remain the least researched aspects of the film industry and certainly of academic film studies. There have been many different models since the 1910s and also many external factors that might overturn prevailing practice. Personally, I have found that since COVID and the success of streamers, we do seem to be in a period of uncertainty about models. Looking around my local cinemas, I’ve noticed that the multiplexes in particular, because they have such flexibility with multiple screens, seem to be trying all kinds of different ideas. In extreme cases, some cinemas attempting to attract arthouse audiences alongside the mainstream, are programming a film for one or two showings each week for several weeks – but only some arthouse releases get this treatment, others play only a few screens and then disappear. On the other hand, I’m amazed that a film like Killers of the Flower Moon could last for several weeks on thousands of screens when its screen average had dropped considerably. It will be interesting to see how the next big films from streamers are programmed.

This is interesting. When I was growing up in Leeds my local cinema was the Shaftesbury on York Road – some of the facade can still be seen at the junction with Harehills Lane. I seem to remember there was always an individual Sunday programme there, and more often than not a different pair of films showing Mon- Wed and Thu-Sat. I didn’t really distinguish between the Sunday slate and the weekly offerings but there was always a pair of films and it was not until I was at university in the early seventies that I encountered the single film offering that I felt vaguely cheated by, as emerging into the daylight after an hour and a half seemed too short an interval. Most of the double bills were comprised with filler material and even the ones that stood out, such as ‘The Snorkel’ seen recently on TPTV, seem pretty poor now. But I did catch ‘Don’t Look Now’ and ‘Blade Runner’ as a double bill, both of which have increased considerably in the estimation of the distributor since their first release.

LikeLike

Your memory doesn’t fail you. What you describe fits the patterns that the data from the Sheffield Gaumont present. Double bills on a Sunday began to appear in the late 1950s. After the 1970s with restrictions lifted Sunday’s programming could begin to develop more imaginatively. Don’t Look Now and Blade Runner in a double bill would have to be quite a programme in the mid to late 1980s. The Shaftesbury had finally closed by 1975 so you must have seen that double bill somewhere else. There is some interesting ‘oral history’ about the Shaftesbury on the Cinema Treasures website.

LikeLike

You are correct about the Shaftesbury. Of the other most frequented venues of that time for me it was probably the Tower on New Briggate which I see closed as late as 1985 although it was probably very run down by that stage. I remember seeing a little mouse running across the aisle between the ranks of seats once, probably well-fed on Butterkist and fragments of choc ice. I can’t recall the film but this would have been a little distracting.

LikeLike