Although the Widescreen Film Festival had already held screenings outside its home base and an afternoon screening of The Battle of the Bulge (US 1965) in Cinerama, the official launch of the festival with a drinks and food reception took place on Thursday evening 28th September. It was followed first by an Indian dance performance by the Devika Dance Theatre in honour of Guru Dutt. Devika Rao’s dance company specialises in Indian Classical Dance forms and she has created a performance that celebrates Guru Dutt’s films. He was born in Bangalore into a family from Padukone in present-day Mangalore before moving to Calcutta. On leaving school he joined Uday Shankar’s Dance Academy at Almora in the Himalayas. When he entered the film industry Guru Dutt began as a dance choreographer in Poona.

Omar Ahmed introduced the screening Kaagaz Ke Phool ending his illuminating talk by reading a translation in English of an Urdu poem. After the dance performance and Omar’s comments on Urdu poetry we were well-prepared for the creative power of Kaagaz Ke Phool. The print was a DCP from Ultra Films which appears to own most if not all the Guru Dutt tiles. The visual quality of the restored print was generally good but I wish the restorers had been able to do more with the soundtrack. Pictureville’s ace projection team struggled with the variable sound levels and this meant that the over-bright orchestral score and multi-voice singing levels were often too high in the auditorium. The quieter passages worked well, however, and the second half of the film was generally much better. The opening songs were perhaps partly responsible for some of the ‘Widescreen regulars’ leaving the screening after only 15-20 minutes. If so, that’s a shame. As Omar Ahmed pointed out, one of Guru Dutt’s legacies bestowed on Hindi classical cinema was his innovative presentation of songs which often spring naturally from the narrative. Rarely in his films do you ever wonder if the song is there just as a free-standing attraction. On the other hand there are occasional songs which are designed to lighten the mood or release tension.

Kagaaz Ke Phool was Guru Dutt’s last film as director (he continued to produce and act up to his death in 1964 at the age of just 39 and a career of barely 20 years). The reaction to the film, first at Berlin and later in Delhi, was so bad that he vowed he wouldn’t direct again and the full appreciation of the film didn’t happen until after his death. Ironically, the failure of a film by a director, played by Guru Dutt himself, is a key feature of the narrative of Kaagaz Ke Phool. Omar Ahmed mentioned one point that strangely I hadn’t thought of before. Because the film was the first South Asian film in CinemaScope (in itself a reason to show the film in Bradford’s Widescreen Festival), distributors and exhibitors across India faced the problem of how to screen it. Omar suggested that Guru Dutt made an alternative version for the traditional Academy screens across India. The question arises about just how many ‘wide’ screens had already been installed since the import of ‘Scope prints from Hollywood that became possible in 1954-5? I hope some Indian film scholars can answer that question. It was Guru Dutt himself who imported the ‘Scope lenses from Hollywood in 1958 in order to make Gouri starring himself and his wife, the playback singer Geeta. That film was planned to be in Bengali and to be shot on location in Calcutta but only a few reels of film were shot as the marriage between Guru Dutt and Geeta was beginning to fall apart. Geeta believed that he was too close to Waheeda Rehman and this would become another influence on the development of the narrative that eventually became Kaagaz Ke Phool.

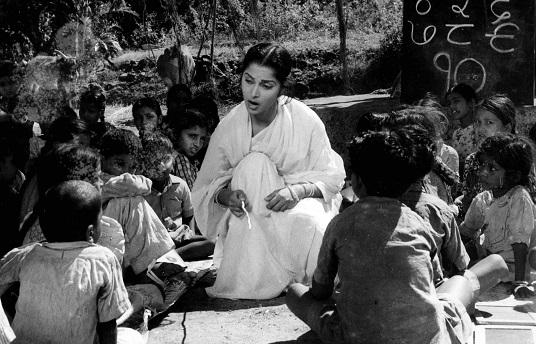

If you haven’t seen Kaagaz Ke Phool you are now probably wondering what the film is all about. In essence this is another film heavily influenced by events and experiences in the director’s own life. It tells the tale of a Bombay film director Suresh Sinha (Guru Dutt) using the device of a long flashback introduced by what appears to be an old man wandering into a large film studio complex and seating himself in the director’s chair on a sound stage. The flashback, based on his memories, reveals how Suresh Sinha became a very successful director after he had a chance meeting with a young woman while sheltering under a tree in a storm. She was Shanti (Waheeda Rehman) and eventually she would become a star in Mr. Sinha’s films. But the director had met her in Delhi after a failed attempt to retrieve his daughter from the boarding school where she has been placed by his estranged wife and her wealthy parents. They will do everything to stop him gaining custody of his young teenage daughter. Caught between his wife’s family and his fascination for Shanti as the woman he has always been searching for as the ideal heroine of his films, Suresh is a doomed man and we follow the trajectory of his rise and fall.

Guru Dutt had actually come across Waheeda Rehman by chance on a trip to Hyderabad in 1955 and he instantly decided to offer her a screen test and soon placed her in a film for his studio. She then quickly became part of his ‘A Team’ of actors and creative personnel – and Geeta became uncomfortable. The flashback device had already featured in Pyaasa in 1957, which also featured a chance meeting between the characters played by Guru Dutt and Waheeda Rehman. Flashbacks were integral to both romantic melodramas and crime melodramas, often categorised as film noir in many international film industries during the late 1940s and early 1950s. Guru Dutt was himself seen as introducing a cycle of ‘Bombay noir‘ films in the early 1950s.

How should we categorise the film? At heart it is a romance melodrama with various expressionist elements in its presentation, including noirish lighting in some scenes. It is also a musical, a comedy and a film about filmmaking, celebrity and fame. The story is set in the world of great wealth and Guru Dutt’s usual co-player Johnny Walker turns up as a wealthy playboy obsessed by horse-racing. His character has a double function in the narrative, first as comic relief (he gets the comic song) and secondly as a male figure in a contrasting marriage scenario. Classical Hindi cinema often borrowed narrative ideas from Hollywood for what were first known as ‘social films’ (i.e. contemporary, not historical or mythological) so narrative elements used here such as the child at boarding school and the separated parents fighting through the law courts are familiar to western audiences. The film is sometimes compared to A Star is Born (the original 1937 Janet Gaynor version is perhaps the best comparison) and sometimes to Citizen Kane (1941), especially given V. K. Murthy’s take on Gregg Toland’s work and the general theme of the decline of the great creator, Kane/Sinha. Suresh does in fact have two ‘Rosebuds’, a doll belonging to Pammi and a sweater knitted for him by Shanti.

Why did the film first fail and then slowly gain classic status? It’s not an easy question to answer. I loved the film the first time I saw it but as is usually the case I have to wonder if it is too sophisticated for the ‘All India’ audience of 1959 – and it features many scenes of upper-class life. On the other hand the songs and the music are terrific and the genuine passion between Guru Dutt and Waheeda Rehman is palpable. I should also point out that the ending of the film is downbeat, another issue for popular audiences (and a contrast with Pyaasa). Suresh experiences one of the most dramatic declines from his peak of a film director adored by millions to an alcoholic living on the margins in poverty while Shanti remains beautiful and noble. In real life alcohol was the main cause of Guru Dutt’s early death, followed a couple of years later by Geeta Dutt, also caused by alcohol. Geeta Dutt was a playback singer on the film, alongside Asha Bhosle and Mohammed Rafi for the male singing roles.

Here’s one of the classic songs from the film sung by Geeta Dutt to represent the thoughts of the Waheeda Rehman character. That must really have hurt her:

Finally, a Trivia Note, his mother named him ‘Gurudutt’ as his first name.