Roy recently included reference to an excellent article by the late Andrew Britton, Sideshows: Hollywood in Vietnam (Movie 27/28 Winter 1980 / Spring 1981). The article ends with a brief reference to an ‘astonishing’ film by Robert Aldrich; Twilight’s Last Gleaming (Lorimar / Bavaria Studio, 1977). Britton commented that “Its distinction consists not simply in its presentation of Vietnam . . . as an objective political reality, independent of the character’s sexual traumas, but it uncompromising rejection of political individualism, whether liberal or ‘heroic’, which is seen quite clearly to lead to catastrophe.” I did manage to track down the film, which offers Aldrich’s direct and uncompromising film style with a very unconventional plot. The basic premise is that a renegade US General (Burt Lancaster), with fellow Vietnam veterans, seizes a US domestic Minuteman Missile silo, and threatens to launch the missiles unless the President releases confidential memos that show that the military knew that they could not win the war in Vietnam, even whilst escalating the conflict.

This is a startlingly political plot to emerge from Hollywood, even in the 1970s. It is not, though, the only commercial feature to pick up political issues normally excluded from the mainstream media. The Sum of All Fears (Paramount, 2002) has Ben Affleck as Jack Ryan [hero of a number of films adapted from novels by Tom Clancy]. Here Ryan has to prevent a US / Russia conflict after a nuclear device is detonated over Baltimore by a secret fascist network. What intrigued me in the plot is that at one point Ryan discovers the device was built using plutonium secretly supplied by the CIA to Israel. The terrorists obtained it when an Israeli jet carrying a nuclear weapon against an Arab target came down in the 1973 conflict. There are few more sensitive no go areas in most of the media than Israel’s battery of weapons of mass destruction.

The film that prompted me to revisit this issue was Eagle Eye (2008, apparently not given a theatrical release in the UK but shown on terrestrial television). This is a stereotypical thriller with lots of action chases and full of scenes reminiscent from earlier thrillers. However, it has a very intriguing premise. In a pre-credit sequence we see a secret Pentagon basement where the military are surveying a funeral in Baluchistan. They suspect the chief mourner is a wanted terrorist. The Secretary of Defence hesitates as the intelligence is not confirmed, but a hard-nosed President gives the order to press the button. Later in the film we learn that the ‘collateral damage’ included civilians. Meanwhile ‘slacker’ Jerry Shaw (Shia LaBeouf) and single mum Rachel Holloman (Michelle Monaghan) become the targets of an all-seeing, apparently all-powerful secret agency. In fact, this turns out to be an all-powerful computer, which is being developed to control US security and anti-terrorist work. The computer has decided that the Presidential Order to kill civilians infringes the US Patriot Act and therefore is setting up the elimination of the 12 most senior figures in the US Government. The Secretary of Defence as a ‘good guy’ is planned to replace them. In a nice touch the computer has called this programme ‘operation guillotine’.

As you might expect the liberal hero wins through in the both of the latter features. It seems to me all three are ‘high concept’ films in the proper sense of the word: [whereas most of the films so labelled seem to me distinctly ‘low concept’]. Liberal viewers presumably get a little frisson when issues that they miss in the daily media turn up in an entertainment feature. Twilight’s Last Gleaming stand out in this trilogy because of the uncompromising downbeat conclusion to the story. It is reminiscent of Dr Strangelove (1963) without the sardonic humour. The last gleaming is presented clearly, boldly and resolutely.

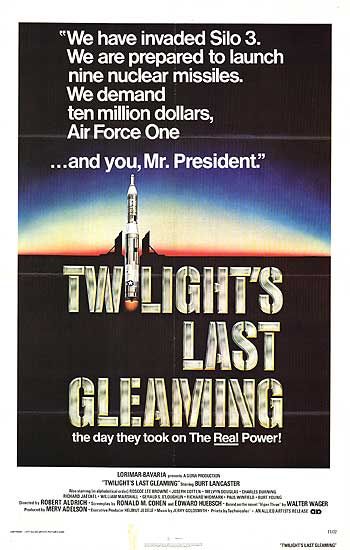

An obvious question is how such subversive plotting works on audiences. It seems possible that the generic features of the thriller exercise hegemony over the more substantial content. The illustrative poster focuses on the genre rather than political content: [in fact the original release was cut, but I am unsure by how much]. In his introduction to his article Andrew Britton argues about Vietnam, and by implication Iraq, Afghanistan, Israel, …, “The very existence of the American state is bound up with such ‘involvements’, for the logic of imperialism is the logic of its own dynamic, and not of undesirable moral decisions which might otherwise (given, perhaps, less venal personnel) have been less undesirable.”

In terms of The Sum of All Fears and of Eagle Eye we have not only an individualised hero but also individualised villains: though in the later case one refreshing plot offers a rogue computer. Twilight’s Last Gleaming is far more impersonal: it is the shadowy military-civilian complex that also figures in J.F.K. (1991). This seems to betoken what Britton describes as “There is a general sense that we can no longer believe in the things in which we once believed, though it’s not clear whether we can believe in anything else; . . .”.

This points to the limitations of even the more radical mainstream features. The actual social relations, exploitation at home, oppression abroad, are never clearly and distinctly set out in the narrative. As Britton suggests it is hard to think of a mainstream film which does actually presently explicitly such relations. In the case of Vietnam you have to move to alternative films like documentaries: Hearts and Minds (USA, 1973) or Far From Vietnam (France, 1967). They, of course, like the Aldrich film, lacked the compromised hero who is supposed to save us, the audience.

See the review for Cutter’s Way.

I found Keith’s piece really interesting and will try to get hold of the DVDs (although Twilight’s Last Gleaming appears only to be available second-hand in VHS – US format) but I was intrigued by his reference to ‘high concept’. I’ve always understood this term to relate to the kind of popular films being produced by independent producers such as as Jerry Katsenburg and Don Simpson in the post-studio era, especially from the 1980’s, where producers would approach studios with a package with some key ingredients. Among these was a story which could be reduced a readily-understandable and -marketable idea, often with a phrase such as Alien = ‘Jaws on a spaceship’ or Top Gun = ‘Star Wars on Earth’. A good modern example would be Snakes on a Plane – no need to say much more! (The ‘concept’ was often referred to as a ‘jingle’). It would be expected to have a catchy title and an upbeat ending and to combine novelty and familiarity and have an upbeat ending. The use of pop music was also important to the mainly youthful audience, and tie-in potential increased the chances of studio funding.

My understanding of the ‘high’ in high concept wasn’t an elevated subject matter or style, rather something that could be conceptualised high above the grubby details which could be worked out later. The idea was that buy studio executives needed to be able to grasp the concept quickly in a pitch, a process satirised by Altman in ‘The Player’. I know these fairly unstable terms evolve and mutate (cf “New Hollywood”). Is there another sense in which it’s used?

LikeLike

‘High concept’ was a term popularised in film and media studies by Justin Wyatt in the mid-1990s when it was quite useful (exactly as Des describes) in identifying the way in which big budget studio films were being pitched. By 2000 I think that the term was disappearing and being replaced by ‘ultra high-budget’ as a descriptor for the major effects-heavy franchise movies, aka ‘blockbusters’ that had become the ‘tentpoles’ on studio slates. Recently the focus has been on 3D versions of the franchises and the ‘concept’ has returned to use with popular genre films.

LikeLike

Des is right about the conventional meaning of ‘high concept’. well explained. However, once I had watched one or two of the movies, the ‘high’ seemed inappropriate. So I was just making a play on words in my comments.

Twilight Last Gleaming is pretty difficult to see: it was screened on terrestial TV, probably in the 1980s: it might have been Channel 4.

LikeLike

I was lucky enough to see Twilight’s Last Gleaming at the NFT in what I think was the uncut version (can’t remember when, probably in the 1980s, but I’m sure the film was advertised as being ‘uncut’). According to the BBFC, the film did receive a UK cinema release in 1977 but this was definitely cut. The 1998 video release in the UK ran 15 mins longer than the cinema release and with the frame-rate speed-up for video that suggests cuts of 20 mins or more for the cinema print.

LikeLike